Stilton: A grand part of our culinary heritage

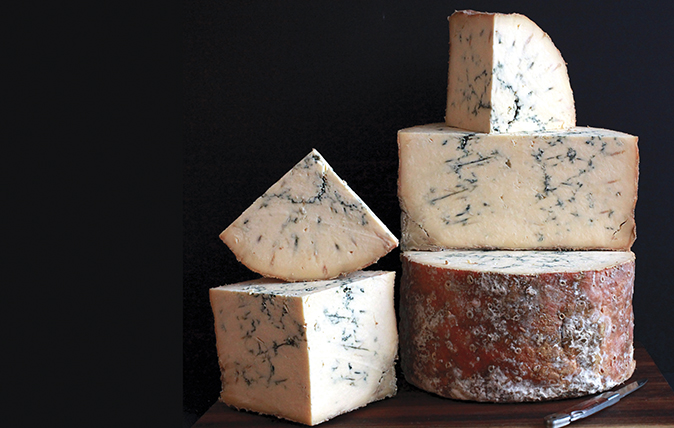

Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a plate of pungent Stilton. Nick Hammond visits the Colston Bassett Dairy to discover the secrets of this British blue cheese.

In the ageing room at Colston Bassett lie scores of truckles. The pungent aroma of dissipating ammonia pervades the still, chill air and, deep inside these truckles of cheese – lined up like toy soldiers the length and breadth of the stores – veins of blue mould are spreading like rivulets of spilled ink.

The glory of the Christmas lunch, the umami-laden topping to a freshly seared steak, Stilton takes its rightful place as a grand part of our culinary heritage. Although its name may have originated from the eye-watering Parmesan-style cheese – complete with weevils – sold in the eponymous village near Peterborough, it’s here in the golden triangle of Stilton-making in the Vale of Belvoir that these world-famous cheeses are crafted and Colston Bassett, in Nottinghamshire, is a standard bearer.

‘We’ve been making Stilton in this dairy since 1913,’ points out dairy manager Billy Kevan. ‘The same farming co-operative runs it and we still use milk from farms no more than a mile and a half around us.’ Mr Kevan is only the fourth cheesemaker to be in charge of production at Colston Bassett Dairy – an extraordinary business that seamlessly blends traditional farming and artisanal cheesemaking with modern technology and stringent hygiene standards.

To call your cheese a Stilton, it must be made according to a strict code and created in Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire or Derbyshire. Here in Colston Bassett, as glowering clouds scud across a slender moon at 4.45am, the cheesemaker’s breath steams as he takes the dozen or so steps from his front door to the dairy. Inside, the lights are bright, the walls and floor spotless, chromed and painted. Wellington boots, smocks and hairnets are regulation attire.

‘It takes about 22 hours to make one of our Stiltons, so there has to be someone here,’ discloses the cheery Scot. ‘Get it wrong at any stage and you’ve wasted your time.’

Each morning, fresh milk from cows just fields away is brought to the dairy, where it’s lightly pasteurised and the liquid mould —which is created in a laboratory and will eventually form the instantly recognisable culture of blue veins throughout the cheese – is added. Rennet and acid-forming bacteria are also stirred in.

Once the mixture has settled, the curds and whey are separated, with the curds then hand ladled before being settled overnight. At the right moment, they’re vigorously mixed with salt. All of this is done – as it has been since day one – by hand. The surplus whey is whisked off to the local piggery.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘The dairy was bought and paid for by locals. Dr William Windley, the village GP, canvassed on his rounds to get enough funds to construct it and £1,000 was raised from 40 people, all of whom were given shares,’ says Mr Kevan. ‘It was built to protect local farming and it still does that to this day. The profits are paid out to shareholders, many of whom are the co-op farmers we buy our milk from.’

The heavy, wet curds are poured into open metal hoops to form the familiar truckle shape and regularly turned during the next few days to remove unwanted moisture. ‘Originally, the dairy would have made about 30 Stiltons a day and employed four to six people. We make an average of 150 a day and employ 28 now,’ he continues.

Once sufficiently dried, the cheese is ‘rubbed’ (smoothing the rough surface with a kitchen knife). After air drying, the truckles are pierced all over to allow oxygen to work its magic on the dormant mould. Each cheese is turned three times a week.

‘The cheeses mature for up to 14 weeks before being packaged for sale,’ elaborates Mr Kevan. ‘Although Christmas is by far our busiest time of year, chefs and home cooks have realised that Stilton can add a huge dose of flavour any time and we have a regular, year-round business. A lot of our cheese goes abroad.’ The French would want you to whisper it, but a lot of Stilton ships there, as well as to other European countries, and the USA is a big market.

Back in the cheese store, Mr Kevan stabs a truckle with his cheese iron – a cross between a switchblade and a corkscrew – to take a core sample. Once a small, creamy scoop of deliciously tangy cheese is smelled, tasted and tested, the core is pushed back into the truckle and sealed with a nonchalant swipe of the thumb. ‘What I’m looking for is creaminess, a rich, uniform spread of blue throughout the cheese and a really mellow flavour,’ he reveals, plunging the iron into the next truckle. ‘In my eyes, a Stilton shouldn’t be crumbly, but actually soft and creamy.’

The cheese is so good that, according to Jason Hinds of Neal’s Yard Dairy, Colston Bassett is the only Stilton his shop will stock. ‘It has this rich sweet/savoury flavour with a texture of fondant butter,’ he says. ‘It’s my desert-island cheese.’

How should you enjoy your Stilton? It’s frowned upon to scoop out a truckle and add Port, but I know of at least one private members’ club in Mayfair in which the chef would be lynched should he suggest bringing an end to this much-loved tableside tradition. A quenelled spoonful of Port-soaked Stilton is one of life’s glories. Nothing says special occasion quite like a whole truckle at the table. If you’re lucky enough to have one, scoop theatrically with impunity – or simply cut generous gouges to feed your guests.

If you have a smaller wedge, don’t ‘nose’ it – that is, cut across the front of the cheese, eventually leaving some poor soul with the rind. Attack from the side, so that all diners get an equal share of the spoils. You can keep your Stilton in the fridge, but not for too long – it’ll dry out and lose some of that special flavour. And you need to give it half an hour or more at room temperature to show it in all its savoury splendour.

Once the dining is done and the Stilton has added a flourish to your occasion, you can save great chunks by wrapping them carefully in foil and freezing them. Simply return them to the fridge for gradual thawing before your next extravaganza.

Colston Bassett Dairy (01949 81322; www.colstonbassettdairy.co.uk)

The best of the rest

Only six dairies are allowed to call their blue cheese Stilton. In addition to Colston Bassett, they are:

- Cropwell Bishop (buy online at www.cropwellbishopstilton.com or from Marks & Spencer)

- Hartington Creamery (www.hartingtoncreamery.co.uk or at Chatsworth Christmas Market until December 5)

- Long Clawson Dairy (www.clawson.co.uk; available in Waitrose)

- Tuxford & Tebbutt (www.arlacheese.co.uk; available in Sainsbury’s)

- Websters (available from www.stamfordcheese.com)

What are the best biscuits for cheese?

Country Life puts six different types of cheese-biscuit to the test, from oatcakes to crackers, and finds our which are

Perfect cauliflower cheese

Cauliflower cheese is a perfect winter warmer

Christmas cocktail cabinet essentials

Gin expert Olivia Williams rounds up essential tipples for your Christmas cocktail cabinet.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.