Kate Stuart-Smith and the creation of her effortlessly romantic English country garden

Stopping spraying and allowing plants to self-seed was the first step in the gradual and brilliant reinvention of the walled garden at Serge Hill, Hertfordshire , the home of Kate Stuart-Smith. Non Morris paid a visit; photographs by Jason Ingram.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When one thinks of the garden at Serge Hill, what comes to mind is a handsome, white-painted Regency villa, its generous windows and comfortable verandah looking down over rolling Hertfordshire parkland — these days, hazy with long grass. A trio of rocking chairs nestled under a spreading strawberry tree create a sense of comfort, everything is settled and calm.

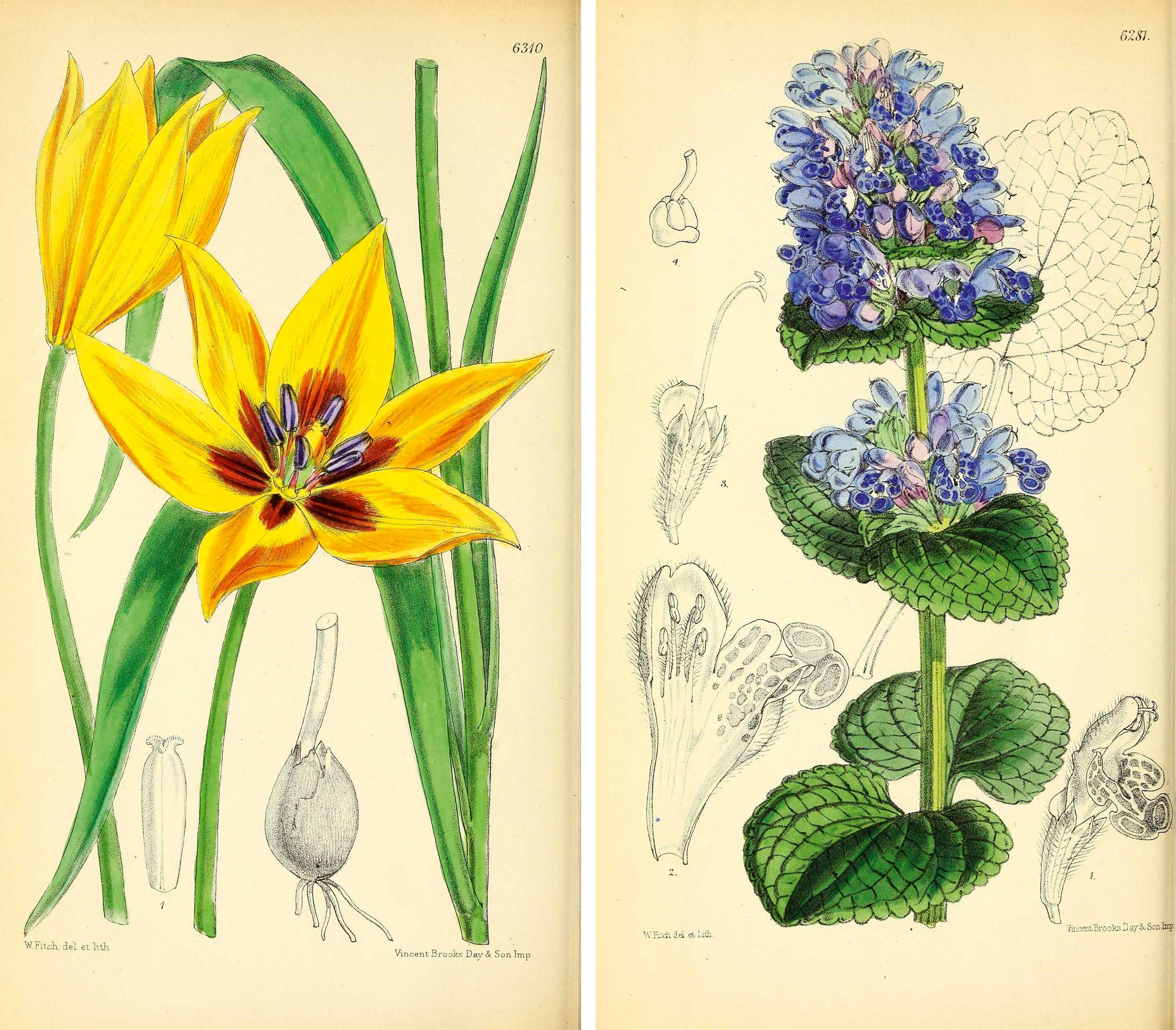

And then there is the Walled Garden at the side of the house. Nothing prepares the visitor for the scented, surging, fairy-tale profusion they have entered. Everyone gasps as they begin their journey along one of its staggeringly beautiful garden paths. You are in a shimmering painting of pale mauve, dark purple, electric green and stately, sky-rocketing whites and yellows. Who has seen mullein used in this way before: a heady upward-dashing cocktail of slender white Verbascum chaixii, ghostly V. lychnitis and great yellow candelabras of the giant mullein, V. bombyciferum ‘Arctic Summer’?

Serge Hill is home to Kate Stuart-Smith and her husband, David Docherty. It is where Ms Stuart-Smith was brought up with her five siblings, one of whom — the internationally renowned landscape designer Tom Stuart-Smith — lives next door in a handsome converted barn surrounded by another remarkable garden.

When her grandfather bought the house in 1926, the lawn beyond the verandah was dotted with circular rose beds. By 1953, when his only daughter, Joan, took over with her barrister husband, Sir Murray Stuart-Smith, the formal rose beds had gone, but the scale of their staff-free, post-war country garden felt overwhelming. The pair decided to set up a market garden, which would allow them to employ a gardener. ‘They had magnificent greenhouses with sliding doors and grew tomatoes, strawberries, chrysanthemums and daffodils,’ explains Ms Stuart-Smith. ‘Having six children in six years gave them access to a small army of additional helpers and we were constantly deployed. It was an amazing education. We learnt to recognise weeds and spent hours in the garden every day during the summer holidays.’

What Ms Stuart-Smith really loved was ‘projects and doing things in teams. I loved the fact that you could embark on clearing a bit of wasteland and turning it into a garden. We would all do it together. Both my parents loved that’. Her mother’s particular passion was for propagation, a skill she passed on from her favourite chair in the greenhouse at the top of the Walled Garden — from where she could see everything that was going on.

Gradually, the Walled Garden changed. It was no longer a market garden, but remained highly productive, with immaculate beds of salad and vegetables, fine stands of artichokes and long rows of pleached apples. An asparagus bed in the sunny top corner gave way to a Hot Patch — a richly coloured summer border with Stipa gigantea ‘planted at the front to hide the weeds’ — and a pergola draped with clematis was designed by son Tom after a visit from Penelope Hobhouse, who declared that the garden needed structure.

Ms Stuart-Smith moved to London after university, where she trained and worked as a garden designer, but returned to Serge Hill in the late 1990s to begin to take responsibility for the garden. But how to make a garden your own when it is a much-loved family garden, albeit with the sensibility of an older generation? ‘The situation here was so different to Tom’s. He began with nothing, an empty field around a barn. I inherited many lovely plants and all this structure. For then, I was very much the under gardener, but, over time, I would have to decide what I wanted to keep and what not to keep. It was hard to know where to start.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Ms Stuart-Smith decided to photograph the garden to work out her approach and, in 2008, when her mother was 80, started redesigning the bottom of the Walled Garden. ‘I was a long way from my mother in the greenhouse at the other end. I felt free to try out perennials and use soft smoky colours rather than her favourite reds. The garden felt austere, I wanted to cover the earth and to have lots of repetition and self-seeding.’

A fundamental change was to stop spraying. Her mother used to rise at 6am on a still day to tackle the gravel. When the spraying stopped, the self-seeding began and everything softened.

Kate Stuart-Smith on creating romance in the garden

You can’t really garden in the way we understand without exerting quite a bit of control, but the key to a romantic garden is to make sure that you can’t see that control

I garden organically and encourage plants to self-seed, which softens everything. It’s well drained here and plants such as Erigeron karvinskianus and Verbena officinalis var. grandiflora ‘Bampton’ love it. My technique is to put a pot of a plant I like on the gravel and leave it to scatter itself

I don’t think you can have a romantic garden without roses, but some roses are more romantic than others. I have realised that ramblers work better than climbers on the front of the house because they are much less stiff. A recent discovery is ‘Purple Skyliner’, almost identical to ‘Veilchenblau’, but with continuous soft purple flowers

Smoky, subtle colours work particularly well in a romantic garden. I love the magical steely blue of Delphinium requienii, the slightly grey-washed blue of Aconitum ‘Stainless Steel’ and the glamour of Salvia turkestanica

The next move was to consider the structural planting. Outdated 1960s conifers and ‘monstrous’ variegated ivy were removed. Plants such as Cotinus coggygria were adapted by ‘pruning them hard to get wonderful bronzy new leaves and lose the heavy redness of a mature plant’ and six fastigiate yews were added to anchor the animated borders. Another turning point was the removal of two spreading cedars of Lebanon, which Ms Stuart-Smith had long found ‘too masculine’. She disliked the way they ‘dictated the landscape’, felt liberated when they were gone and decided to take out a beech hedge, too. This area is now a wildflower meadow with a mown path through a relaxed grove of the exquisite crab apple Malus hupehensis, a place of calm after the thrilling headiness of the Walled Garden.

By the time Lady Stuart-Smith died in 2015, she had described her daughter’s changes as ‘astonishing’. The garden at Serge Hill is an exemplary balance between old and new. The patiently propagated box plants are now glorious bulging hedges, the perfect foil for wine-coloured sunflowers and dazzling foxtail lilies. The layout within the Foster & Pearson greenhouse continues because it works so well, but, instead of compost, the bays outside are full of salvias, Verbena bonariensis and tumbling squash. ‘It was much more functional before. I want people to go “wow” at the romantic abundance as soon as they arrive.’

Ms Stuart-Smith has created a garden that is thoughtful and generous, experimental and passionate. She is aware that her gardening style is intensive and that she could not manage without the commitment of her gardener Richard Spicer and her Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) volunteers. She knows too that future change is inevitable. ‘Perhaps the next generation will simply divide the Walled Garden into allotments and plant trees. I would probably encourage them, but this feels right for now’.

The garden at Serge Hill, Belmond, Hertfordshire, and Tom Stuart-Smith’s Barn are open to private group visits during June and July — pre booking essential via www.tomstuartsmith.co.uk.

How to have cut flowers all year round

Country Life visits a thriving cut-flower nursery in Kent to find out how to grow flowers all year round

The best garden designers and landscapers in Britain

A beautiful country house is as much about its surroundings as its bricks and mortar, something that the best garden

The revival of Chatsworth's great wooded bank: 'A mountainous place of woods, springs and birdsong'

It has taken three years and more than a quarter of a million plants to bring brilliant new life to

Credit: Savills

A vast Georgian home that’s been immaculately restored, with gardens by a man who’s won eight gold medals at Chelsea

Wycliffe Hall, the very picture of a grand Georgian country house, and has been treated to money-no-object restoration in the

Alan Titchmarsh: The best gardening books in my library of 5,000 volumes

The best of Alan Titchmarsh's gardening books have helped shape his career — he takes a look at some very special

The bustling plant nursery behind some of the Chelsea Flower Show's best gardens

The designer gets the applause, but behind every successful Chelsea show garden is a nursery that supplies the plants. Val