Charles Quest-Ritson: Moving back to an English country garden has been a joy — but we do miss the cheese

Giving up life on the Cherbourg peninsula to return to England has brought huge happiness to Charles Quest-Ritson — but there are still a few things he misses.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I have spent the past 14 years living, for as much as the tax laws allow, in an unfashionable corner of Normandy. Why?

Well, largely because I wanted to garden in a mild climate with fertile soil in which I could grow acid-loving plants. My long-suffering wife pleaded caution, but eventually acquiesced: she likes camellias. And almost all our married life had been spent in areas of chalk upland.

I grew up in a woodland garden, where we planted rhododendrons, azaleas, camellias and all those funny ericaceous shrubs that no one notices unless they’re in flower. It was a joy to have nine acres of French woodland into which to introduce rare trees and shrubs, plus three acres of ancient cider-apple orchard where we could grow roses — we ended up with more than 1,000. What’s more, blue hydrangeas and blue Meconopsis poppies were possible for the first and last time in my horticultural life.

Most Brits in France live further south, in wine-growing areas such as Vaucluse, Charente-Maritime and the Dordogne, so why did we choose the Cherbourg peninsula? Two reasons: first, I hate hot summers and cold winters, but am happy in wind and rain; plus you can’t grow Rhododendron macabeanum south of Caen.

Second, the fastest ferries to England run from Cherbourg, so we could have breakfast in Hampshire and lunch in the Cotentin.

In 2014, our daughter and son-in-law bought a house in the Itchen Valley and made us an offer: ‘Come and live in the west wing and make a garden for us.’ The idea of spending our twilight years among our children and grandchildren was irresistible.

We put our grandly named domaine on the market and hooked a purchaser almost immediately, but she ratted on us at the last moment — French law allows the buyer, but not the seller, to change their mind even after contracts have been signed and exchanged. Then the French property market collapsed. I was, therefore, completely unprepared for three would-be buyers all turning up last Christmas.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Now we are back in England and, once again, the soil is chalk. I started bringing plants over from Normandy some years ago and am struck by how feeble is the growth of the roses that galloped apace in the sandy clay soil of the Cherbourg peninsula. Some have reached less than half the size that they quickly attained in France.

Yes, I can cultivate roses on chalk if I fuss around and feed them — and will try to do so, although it’s generally a mistake to seek to grow anything that needs lots of coaxing to give of its best.

There are many plants that think our thin soil is wonderful and will perform very much better here than in the damp, warm Cotentin. Bulbs, for example. Acres of daffodils have made our Hampshire bulb farmers rich. Why have I admired them so much in other people’s gardens, but never grown hordes of them in my own?

Chalk is remarkably free-draining, which means that our sun-soaked hillside resembles a Mediterranean garden in summer. Cistus and rosemary were always rotting off in Normandy — so did artichokes, pinks and spurges — but here in Hampshire, I am planting sweet-scented sweeps of maquis plants, not only shrubs, but paeonies, cyclamen and irises, too. And lavender in abundance.

I am a natural optimist and, unusually for a gardener, I love change. Every garden is better than the last. In fact, life gets better, year after year, in almost every way. When I was 50, I only hoped to survive long enough to see my first grandchild born. Now I have the pleasure of knowing that he is going to university in September.

And yet… I wish we had stayed long enough in Normandy to see our plants of Cornus capitata flower for the first time. They came as seedlings from Martyn Rix 10 years ago and are now 10ft high. And then there’s the handkerchief tree Davidia involucrata, planted on our arrival in 2006, and still not bearing its gorgeous white bracts. There’s a selection called Sonoma that Roy Lancaster praises because it flowers as a young plant; it’s on my must-buy list.

In fact, I have only two regrets on leaving France, and neither of them has anything to do with gardening. The first is that I used to play the organ at Masses, weddings and funerals in our local church, but I will never be good enough to do so in Winchester. The other comes from having lived in an area that carries the AOC designation for Camembert. Milk from the fields around us went to Normandy’s greatest co-operative, Isigny Sainte-Mère, to make the cheeses that are so difficult to find in England. I miss them. That is why we say that our return to England has been a move from cheese to chalk.

The best honeysuckle to grow in your garden – especially if they’re gifts from now-departed friends

Charles Quest-Ritson extols the virtues of delightful honeysuckle.

What to plant if you're thinking of putting a willow in your garden

Charles Quest-Ritson offers advice on this incredibly vibrant plant.

Credit: Alamy

The daftest plant name in English, and how it belongs to a wonderful flower just starting to show its potential

There are a lot of silly names for flowers our there – and Charles Quest-Ritson has a chilling warning for those

Credit: Alamy

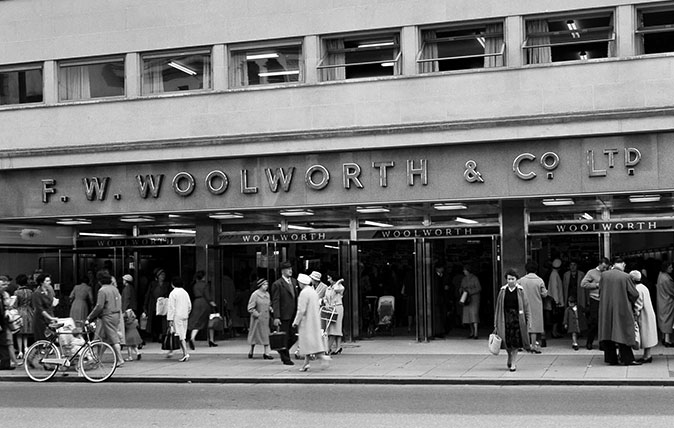

The day that Woolworths accidentally sold me an endangered species

Charles Quest-Ritson reminisces about the day his bargain purchase of a cyclamen in Woolworths proved to be something rather special.

Charles Quest-Ritson is a historian and writer about plants and gardens. His books include The English Garden: A Social History; Gardens of Europe; and Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World. He is a great enthusiast for roses — he wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses jointly with his wife Brigid and spent five years writing his definitive Climbing Roses of the World (descriptions of 1,6oo varieties!). Food is another passion: he was the first Englishman to qualify as an olive oil taster in accordance with EU norms. He has lectured in five languages and in all six continents except Antarctica, where he missed his chance when his son-in-law was Governor of the Falkland Islands.