The romance of the rose, and how it became the flower of love

Generations have sought that unattainable mystical creature, the perfect rose: shapely, dark red and sweetly scented. What is it about this flower that holds us so in thrall, and why are roses associated with love? Charles Quest-Ritson finds out.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

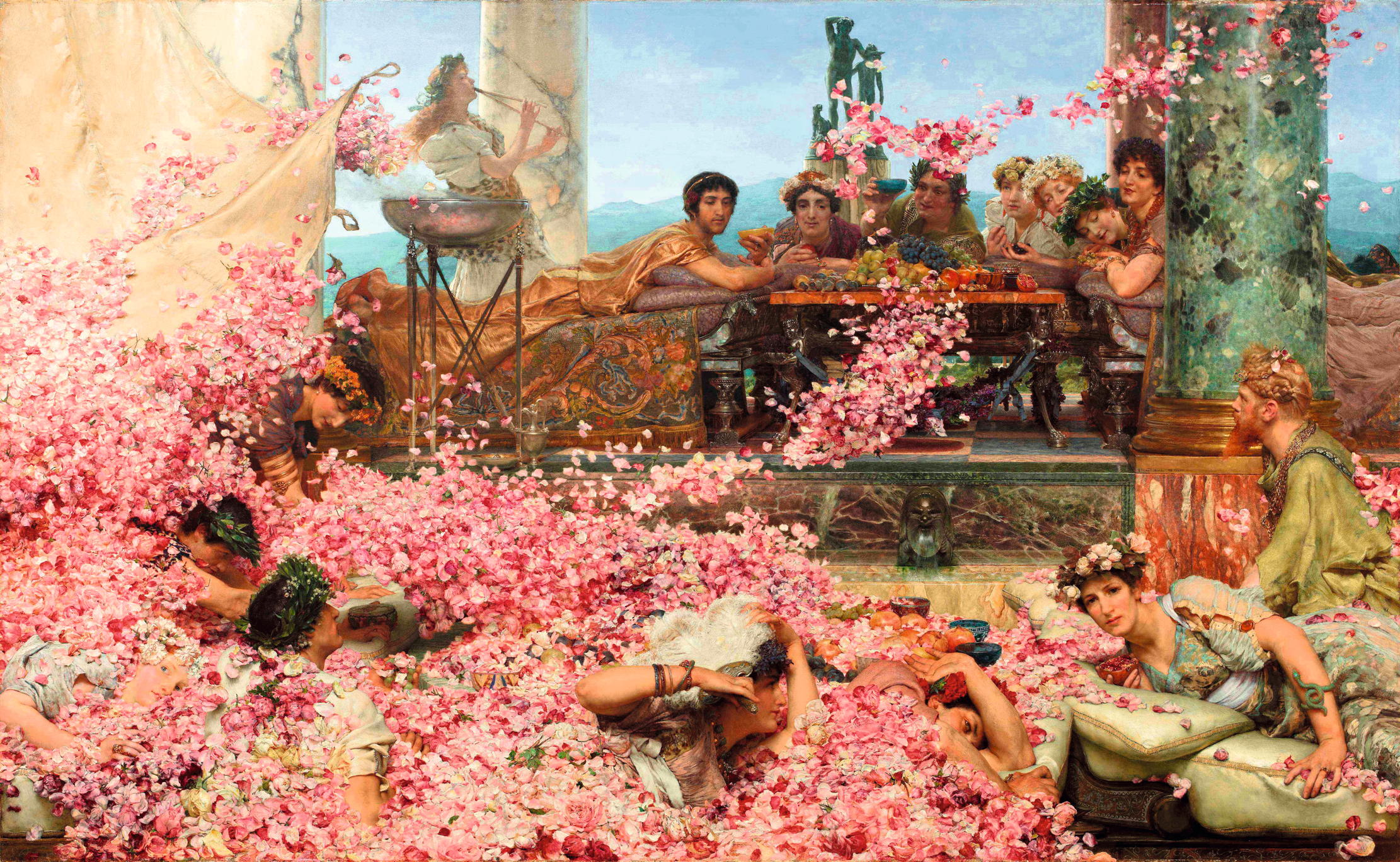

Roses are the world’s most popular flower. And they were among the first to undergo domestication, both in China and in the Middle East — the famous Fertile Crescent that was the cradle of settled civilisation as we know it. In Roman times, roses were imported every year from Egypt, where they flowered many weeks earlier, for feasts and festivals — think of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s painting of the Emperor Heliogabalus smothering his roistering guests beneath an avalanche of rose petals.

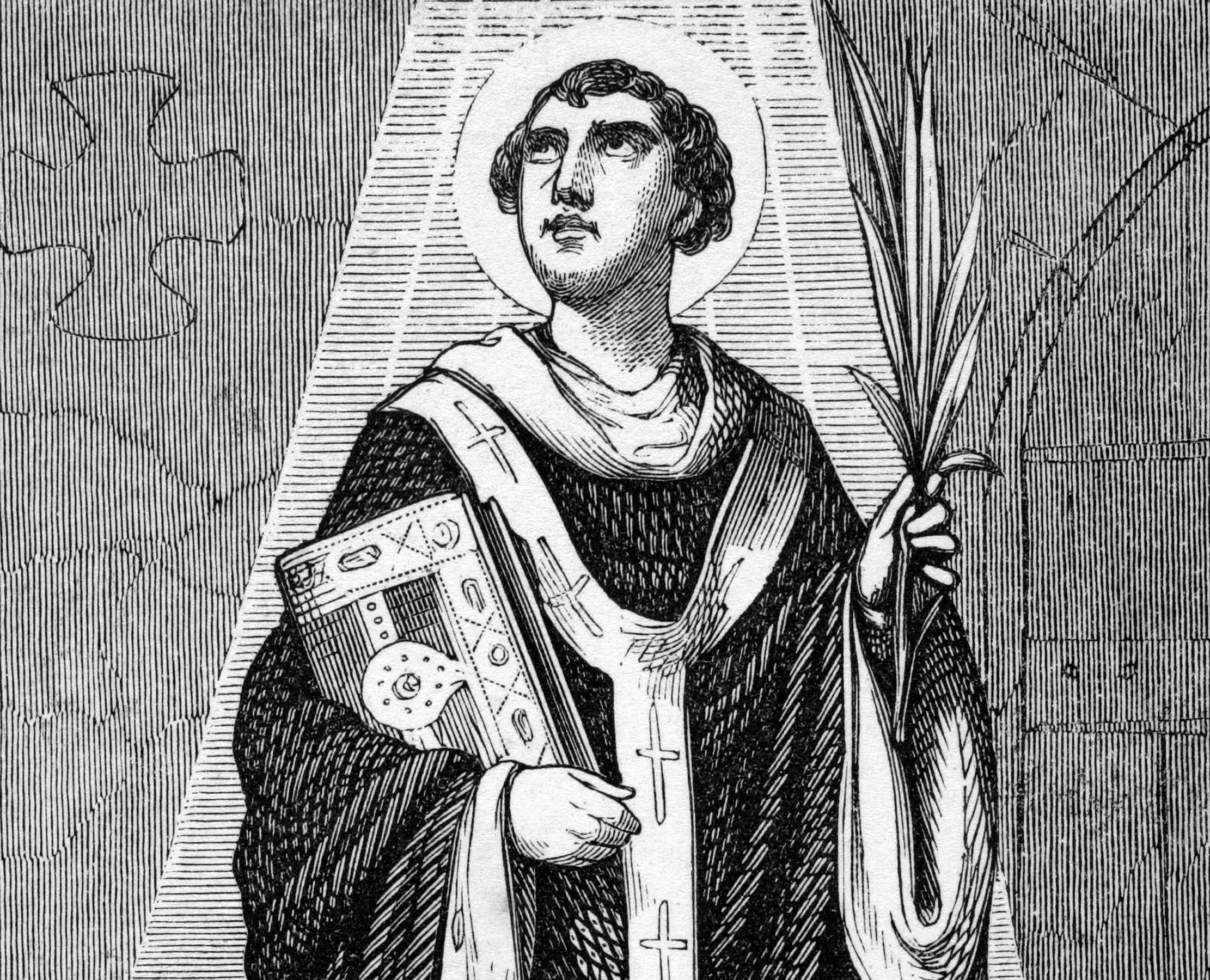

After some hesitation — because roses were associated with heathen tales of Venus and Adonis — the Christian church absorbed the symbolism of roses into its allegories and practices. The red rose came to represent Christ’s suffering and is often seen in Medieval and Renaissance art. The usual subject for these images was Rosa gallica ‘Officinalis’, the richly scented beauty with delicate petals that we know as the red rose of Lancaster.

Red roses come in endless shades, hues and degrees of intensity. Old roses — gorgeous Gallicas such as ‘Charles de Mills’ — often have a purplish tinge to their redness. This was the norm until bright-red roses that sparkle in sunlight were introduced from China at the start of the 19th century. Both are in the ancestry of all our florists’ roses today — the fragrant French rose and the brilliant-red Chinese. If you look carefully at a red rose, you often find that it has a bewitching white stripe or two at the base of the petals. This is a gene that came from China, with the first perpetual-flowering roses. Treasure it.

The great development of roses began in the 19th century, first with Gallica roses — large, many-petalled and sweet-scented, but once-flowering — and the Damask roses, slightly smaller, but sometime repeat flowering, a trait that was seen as a desirable improvement. Further roses followed and new classes were recognised — Noisette roses, Bourbons, Teas and Hybrid Perpetuals — distinguished by scent, size, colour and whether they flowered perpetually or, at least, recurrently. The names alone breathe romance with every syllable. What man could fail to be aroused by ‘Cuisse de Nymphe Emue’?

Modern roses are complex hybrids, far removed from their wild ancestors, but they embrace the best genes from eight or 10 species — and, over the ages, each was selected for the qualities it brought to the whole. Do not hold romantic thoughts about those wild ancestral roses — there is little enjoyment to be found in scrambling dog roses or prickly Scots roses. Milton knew that before the Fall of Man, roses were thornless, but, when Adam and Eve were chased out of the Garden of Eden, roses acquired thorns to remind them of their folly. Most modern roses still have prickles — hybridists have not yet managed to breed them out — and the few that are almost ‘thornless’, such as ‘Zéphirine Drouhin’, still have little barbs on the backs of their leaves. Its scent, however, hangs in the air like a perfumed canopy.

Roses had a special meaning in the Language of Flowers. Red roses meant ‘I love you’ — and still do. A single stem with one red rose is a promise of fidelity: ‘You are the only one.’ Two red roses reciprocate the passion: ‘And you love me, too.’ And 50 roses — which was considered quite over the top — told your beloved that ‘my love has no bounds’.

Nowadays, we are invited to celebrate National Red Rose Day, which takes place every year on June 12. The thing to do, apparently, is to scatter some petals on your beloved’s doorstep and scamper away undetected — romantic, perhaps, but also rather timid. Red roses are made for Big Statements. They are eternal symbols of a love that transcends death.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

St Valentine’s Day — February 14 — is the date for lovers and it comes at the right commercial interval to liven up the florist’s business between the high points of Christmas and Mothering Sunday. Red roses are grown in Colombia and Ecuador for the US market and Kenya for the European. Those destined for England are usually raised under glass, picked at the perfect moment, then sorted, packed into boxes and flown in refrigerated crates to Aalsmeer in the Netherlands, where they arrive in time to be auctioned next day. Then, you can buy them in prime condition in your local florist’s shop in Belfast, Bristol or Bermondsey within 48 hours of cutting. About eight million or 570 tons of roses were imported into the UK for Valentine’s Day last year. It’s a miracle of modern marketing. But query — what will your beloved say when you murmur that ‘these roses have come all the way from Kenya — specially for you’?

Spoilsports bat on about ‘the true cost’ of hothouse roses — meaning pesticides, high water usage, energy consumption, environmental degradation, global warming and anything else they can add to make us feel guilty. That’s not fair — St Valentine’s is a day for breaking the rules and committing yourself to unconditional love. And there is no doubt that everyone involved, from African rose-pickers to the busy ribbon-tiers at Interflora, is proud to work in an industry that brings such pleasure to so many. Yes, there’s the problem of your carbon footprint, but it’s only once a year and you can make amends. After all, there is also much to be said for asparagus from Peru and oranges from South Africa — and even for wine from Australia.

Roses permeate every expression of our culture. Robert Burns’s love (although he probably had too many of them) was ‘like a red, red rose’; for Robert Browning, it was ‘roses, roses all the way’; and Sir Edmund Waller’s ‘lovely rose’ was bidden to ‘tell her that wastes her time and me… [to] come forth, suffer herself to be desired, and not blush so to be admired’. No less explicit is Octavian’s presentation of a rose to Sophie, in Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier — never were female voices more beautifully intertwined. Roses remain a deep source of inspiration for artists, from the Tea roses so beloved by Henri Fantin-Latour to the opulent garlands that surround Dutch still-life oil paintings in Oxford’s Ashmolean or Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum.

Modern roses represent the climax of generations of human endeavour in search of horticultural improvement — that unattainable mystical creature, the perfect rose. Enterprising nurserymen urge us not to waste money on cut roses that will soon droop and die, but to buy a real living rose, a bush with roots, a gift that will give pleasure for years to come. You need to cut gorgeous roses from your own plants, they say, and put them in a vase indoors to appreciate the full expression of their beauty. It is hard to quarrel with their argument — what would our gardens be without rich crimson ‘Général Jacqueminot’, ‘Crimson Glory’ or ‘Ena Harkness’, all of them dripping with intensely sweet scent? But do not expect to find garden roses flowering in time for this week’s jollifications. Go, instead, to Hampshire’s Mottisfont Abbey in June, when all the antique roses in the collection assembled by Graham Stuart Thomas are heavy with flower and scent. It is the loveliest garden in the world — no one can fail to be overwhelmed by the beauty of the individual flowers and the way they combine with lilies, peonies and other good companions. The National Trust believes it to be the best of all the hundreds of gardens in its portfolio. We can but speculate on how many proposals of marriage have been made at peak season within Mottisfont’s mellow walls.

So wherein lies the romance of a bunch of red roses on St Valentine’s Day? Each bloom will be a perfect bud, long-stemmed and bred to last for up to a fortnight in water. But nothing is simple about roses: florists’ roses are scentless. The gene for a long vase life is the antithesis of the gene for scent. And shape is a problem, too. Those high-centred beauties we give or receive in memory of St Valentine have a conical outline whose inner petals emerge from the outer ones, but seldom open out in the vase. What people long for is the romantic, open, old-rose shape, rather than the tight bud that never expands to reveal a pretty arrangement of petals within.

Many would say that David Austin’s roses come close to that ideal of the perfect rose. His roses, surely the most popular now in English gardens, combine the opulent scent and romantic beauty of old roses with the ability to flower repeatedly. ‘Thomas à Becket’ is perhaps the best crimson example today. But it is not perfect… it is capable of improvement. Happy the man or woman who invents a rose that is shapely, dark red and sweet-scented, a rose that is thornless and resistant to all diseases, a rose that will last a full month in water. He — or she — will become very rich. And nothing is more romantic than a millionaire.

St Valentine’s Rose: A saint reborn

There is a rose named ‘San Valentin’. It is a pale-pink miniature rose, bred by the Catalan rosarian Simó Dot in the 1960s. For many years, it was thought to be extinct until a solitary surviving plant turned up in Madrid’s Botanic Garden in Spain, next to the Prado.

An enterprising Italian rosarian had it propagated and decided to relaunch it at Terni, in Umbria, where the original St Valentine was bishop. The current bishop, not a native of Terni, came along and put people’s backs up by saying that St Valentine didn’t exist — he was only a myth. I was asked to give a speech praising the Saint as a symbol of true love and then a more friendly priest blessed the roses. The celebrations ended with a toast of proper Champagne, followed by a dinner in the City Hall. ‘San Valentin’ is now alive and well in Italian nurseries and gardens.

The true story of St Valentine, his legend and legacy of love

Whatever the truth of the real St Valentine, the middle of February has been a favourite time for lovers since

Credit: Getty Images

Curious Questions: Why do we say it with flowers?

Post-Valentine's Day, Martin Fone takes a look at the true meaning behind flowers, decoding what each individual bloom says about

Curious Question: Was St Valentine beaten to it by 1,000 years by the Welsh patron saint of love?

The arrival of St Dwynwen's day on January 25th prompts Martin Fone to recall the tale of a saint whose

Charles Quest-Ritson is a historian and writer about plants and gardens. His books include The English Garden: A Social History; Gardens of Europe; and Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World. He is a great enthusiast for roses — he wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses jointly with his wife Brigid and spent five years writing his definitive Climbing Roses of the World (descriptions of 1,6oo varieties!). Food is another passion: he was the first Englishman to qualify as an olive oil taster in accordance with EU norms. He has lectured in five languages and in all six continents except Antarctica, where he missed his chance when his son-in-law was Governor of the Falkland Islands.