The secret life of duchesses, from nursing and sculpture to flying aeroplanes at retirement age

Being a duchess isn't all going to lunches strolling through the shrubbery – they have a job to do. Jane Dismore explores the achievements of some of our great chatelaines, past and present.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

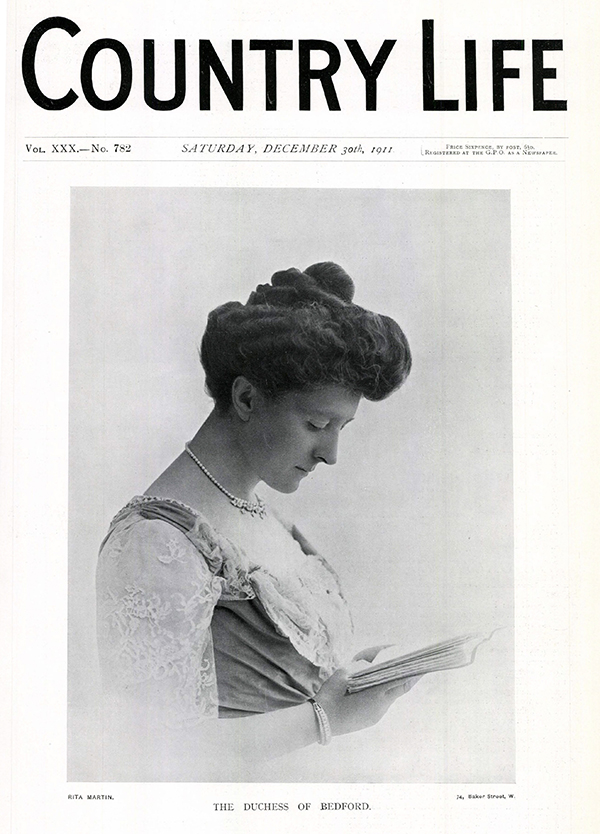

A century ago, Britain was staggering through the last year of the First World War, its old country houses still trying to cope in their crucial role as military hospitals. At Woburn Abbey that summer, Mary, Duchess of Bedford, a 53-year-old nurse, radiologist and the wife of the 11th Duke, watched in dismay as vital supplies floated past her in several feet of flood-water, caused by a vicious storm.

Despite the damage, however, the soldiers in the hospital that Mary had created within the historic house were safe. Here was the only hospital in England, noted one newspaper, ‘where the patients can lie in bed and watch buffalo and llamas grazing outside the windows’.

Before Mary would be honoured for her nursing and famously went on to take up flying, breaking records and achieving her solo licence at the age of 66. In protesting against the taxation of women, she also played a part in securing the vote.

However, although 1918 marked a more hopeful future for many, the outlook was bleak for the country’s heritage. Young men who should have returned to their family estates, with the expectation of inheriting them, never did. Harsh economic factors prevalent since the 19th century were making life increasingly difficult for landowners. The demolition of many large houses after the next World War would make depressing news.

However, many still survive, thanks to their owners’ efforts and the world’s enduring fascination with British history. Today’s Duchess of Bedford, Louise, is keenly aware of the responsibility to ‘keep Woburn going and moving forward for the next generation’. Although getting the vote made no difference to women’s inheritance rights – most titles still pass down the male line – many women are the creative force behind the estates, striving to achieve a successful fusion of the old and the new and to keep the visitors coming.

A whirlwind of energy and ideas, this year, Louise – mother to Alexandra (17) and Henry (13) – has been overseeing Woburn’s exhibition commemorating the bicentenary of Humphry Repton. Since becoming Duchess in 2003, she has supervised the transformation of the gardens, working with manager Martin Towsey and his team to re-create Repton’s plans. The gardens continuously evolve; last year, the Rosarium Britannicum was opened on the site of the original 19th-century rose garden.

The constant challenge is ‘to introduce new and enjoyable activities for our visitors’. It was her husband’s grandfather, the 13th Duke, who opened Woburn to the public in 1955 and most of the state rooms haven’t been refurbished since. Following ‘a painstaking, but incredibly worthwhile’ process of consultation with experts, work will start in September 2019, enabling visitors to see more of the historic collection and enjoy updated facilities on the 500-year-old estate.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Louise is also patron of many charities: ‘If you’re in a position to help people, you should.’ These include the Friends of Bedford Hospital, which developed from a cottage hospital started by Mary, and NSPCC Bedfordshire, for which the current Duchess hosts a gift fair. In London, she is, fittingly, a patron of the Bloomsbury Festival, which takes place in that unique area owned by the Bedford Estates since 1669 and celebrates Bloomsbury’s pioneering creativity.

At Alnwick Castle, Jane Northumberland can lay claim to three firsts since becoming Duchess in 1995. She’s the first in that title who isn’t from the aristocracy, she was the first woman to be appointed Lord-Lieutenant of the county and she’s the force behind the first major garden to be created in Britain since the Second World War.

Although becoming Duchess wasn’t something she expected or wanted when she married Ralph Percy in 1979 – his father was then Duke and his older brother the heir – she has risen to the challenges presented by her position. After turning the castle from ‘a museum’ into a family home, she has overseen its development into a major attraction in the economically challenged North-East.

The Alnwick Garden benefits numerous community-project groups and has generated many millions of pounds for the local economy, but it hasn’t always been easy. Jane has had to develop ‘a very thick skin. You just have to get on with the job and remember why you’re doing it. Hopefully, if your values are right, everything else will be’. She’s also patron of more than 160 charities, together with the Duke.

In 1740, Jane’s favourite predecessor, Elizabeth, achieved the continuation of the Percy line in the absence of male heirs by marrying Sir Hugh Smithson. He took the Percy name and, in 1766, they became the 1st Duke and Duchess of Northumberland. Elizabeth was a compulsive collector of all manner of curiosities, a pastime that was usually the preserve of men: hers was one of the very few collections independently assembled by a woman during the Georgian period.

A keen diarist, Elizabeth’s love of record-making included household tips, the most bizarre of which, such as ‘To Kill Worms in the Handes and Feete’, Jane includes in her own books. Elizabeth and Sir Hugh patronised artists and architects, employing young Robert Adam at Alnwick and Syon House, the interior of which he remodelled.

Today’s Duchess recognises the significance of historic houses beyond their inhabitants: ‘Alnwick Castle and Syon House are far more important than any duke or duchess that’s in them. The buildings will go on and on.’

Ensuring that they do go on is seldom the glamorous task that some might imagine. ‘It’s not like that film image, where you marry and walk about in the shrubbery all day,’ says the Duchess of Argyll at Inveraray Castle. ‘You’ve got a job to do.’

When Eleanor married Torquhil Campbell in 2002, he was already Duke and Chief of Clan Campbell, following his father’s sudden death the previous year. Today, the castle enjoys increasing numbers of visitors, thanks to Eleanor’s background in PR and her ‘hands-on’ approach: ‘You’ll do anything to keep the place going.’ She has no problem with having strangers in their home, adding: ‘It’s an amazing house, so to share it is rather nice.’

The local community has always been closely involved with the estate. Eleanor, a mother of three, continues the tradition of a children’s Christmas party and is chair of the regional Best of the West Festival, held in the castle grounds. Adding to her existing charity commitments, she has become patron of Richmond’s Hope, which helps children who have suffered major bereavement.

Eleanor is inspired by Princess Louise, whose marriage to the future 9th Duke of Argyll saw her become Duchess. The sixth child of Queen Victoria, born in 1848, the independently minded Louise pioneered education for girls at a time when male physicians believed it could cause over-exertion and damage the reproductive organs, as well as supporting women’s suffrage.

Her artistic talent was nurtured and she became a significant sculptor, known particularly for her statue of Victoria in Kensington Palace Gardens. Louise also made a permanent impression in Canada, where her husband was Governor-General; she was patron of many women’s charities and helped establish the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and National Gallery. Louise was, says Eleanor, ‘a truly extraordinary woman’.

Jane Dismore is the author of ‘Duchesses: Living in 21st Century Britain’, published by Blink Books

The life of a 21st century Highland clan chief, from managing 60,000 acres to manning the tills at the gift shop

Their family histories are full of heads on spikes and villages being razed to the ground, but modern Highland clan

Dukes and their dogs: Why Britain's aristocracy are just as mad about their canine friends as the rest of us

Stylish canines have long been a duke's or duchess's best friend, as Matthew Denison found out.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.