Arts and Antiques sales: Old wine bottles and Chinese ceramics

Huon finds there is money in old wine bottles, and a Chinese ceramics sale at Sotheby's has some impressive sales

When I was an undergraduate, a friend and I discovered in a forgotten college cellar a binfull of-alas empty-sealed wine bottles. They dated from the late 18th or early 19th century and we knew that they could be worth up to £50 each. We also knew that the last time such a cache had been found, the college authorities had smashed it up and used the shards to top the walls in order to deter nighttime climbers. Accordingly, we laid down a number for ourselves before informing our tutor, who, in fact, gave us retrospective permission to do so.

Despite St Matthew's dictum, men did indeed put new wine in old bottles. Inns and collegiate institutions, followed by aristocrats and other individuals who bought wine in bulk, would decant it into their own bottles marked with a glass seal, so that they could be returned and used again and again. The practice seems to have originated in Oxford. Except for the four still in my kitchen, I sold my bottles many years ago; so did my friend and I expect that the college did well by the rest. Occasionally, sealed bottles come up in the saleroom and, whenever I see TCCR- Trinity College Common Room- I wonder if it is one of mine. All Souls, from which I used to have one, also appears from time to time.

The importance of seals to collectors was evident in four lots in a May sale at Woolley & Wallis of Salisbury. The first, of two unsealed 18th-century bottles, estimated to £150, failed to sell. Then, six bottles together made £1,011 -one with a crest, the initials I. F. and the date 1748, one with a ducal coronet and a B for Buckingham, one All Souls and two Trinity. A single ASCR -All Souls Common Room- reached £126.

The fourth lot was a much older specimen going back to the 1660s (above), the earliest days of English glassmaking. It was an onion-shaped ‘shaft and globe' type and it had an unidentified seal of a shield with three fleurs de lys. It had been dug up in Wiltshire by a member of the vendor's family in about 1960 and it sold for £8,216.

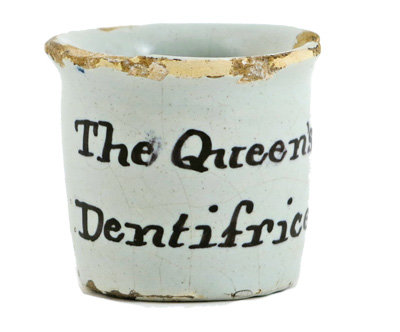

Among the ceramics in this sale was a simple, little white delftware pot (above), which was estimated to £1,200 and sold for £2,149. It dated from, perhaps, the 1770s and was inscribed in manganese: ‘The Queen's Dentifrice'.

From 1727, the post of ‘court operator for the teeth' had been held by members of the Hemet family, who made their fortunes in dentistry. The first, Peter, died worth £20,000 in 1747 and, by the time of his death in 1790, the third, Jacob, Queen Charlotte's operator from 1766 and dentist to the Prince of Wales, was selling these little pots containing ‘The Essence of Pearl and Pearl Dentifrice' for 2/6d each. Its ‘great balsamic qualities... are found most certainly to preserve the teeth from decay and to prevent those injured by neglect from becoming worse, shield them against all putrefaction, fasten such as are loose, make the foulest teeth become white and beautiful, entirely preserve the enamel, and render the breath delicately sweet'. What might an American dentist charge for that?

There were also several porcelain eyebaths scattered through this sale, including Lowestoft, about 1765, 1770s Meissen, 1790s Caughley, 1820 Nymphenburg and 1900 Limoges. All were of the conventional shape and form, except the Nymphenburg at £838, where the gilt basin was supported by a kneeling putto. The most expensive, because of its rarity, was the Lowestoft at £3,413 (above) and the cheapest the Meissen pair (with a modern vase) at £316.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The eye and hands of a collector need to be exercised constantly, just like other muscles. Gradually, they should become swifter and surer in their reaction to quality and beauty and, as they do so, their owner's taste will become ever more refined. I hope that this is not pretentious whimsy and that even, say, collectors of Warhol may eventually mature to deeper pleasures.

If I had collected Chinese porcelain, I might well have begun with the familles jeune or rouge (‘foreign colours', as the Chinese called them), but I hope that I would have moved backwards in time and forwards in taste to the quiet certainty and simplicity of Song (AD420-589). As it is, I particularly admire the undecorated creamy-white glazed early ‘Ding' dishes and also the rather later wares, with delicately moulded or incised, decoration. If there is any colour on these, it is a little copper around the rim. You have to look carefully to enjoy the subtlety to the full.

There were a number of such dishes in a mid-May Chinese ceramic sale at Sotheby's, one of which seemed particularly attractive to the market. The interior of the 7.in diameter dish was finely moulded with a dragon encircled with keyfret and lotus bands and one could almost taste the creamy glaze. Estimated to £15,000, enthusiastic bidding took it to £62,500 (above).

At the end of April, there was a sale at Christie's South Kensington that had been assembled from the collections and stock of four leading decorator/dealers: Robert Kime, David Bedale, Piers von Westenholz and Christopher Gibbs. The result was titled ‘The English Home' and was mostly restrained and stylish, if rather out of tune with today's fashions.

As a lover of libraries and metamorphic furniture, I was attracted to a William IV mahogany armchair in green leather (above), despite its heavy appearance, because the seat covers a set of steps. I am surprised that I did not mention it when it sold for £4,000 in 2010; this time, it was only £2,500.

Pick of the week

In the 19th century, France produced four royal ‘nearly men'-heirs to the throne who never actually sat on it: the duc de Berry, best hope of the restored Bourbons, assassinated in 1820; his posthumous son, the duc de Bordeaux; Ferdinand Philippe d'Orléans, killed in a carriage accident in 1842; and the Prince Imperial. The duc de Berry and Ferdinand Philippe, both collectors and patrons, were real losses in terms of culture, as well as national reconciliation. A mid-May sale at Sotheby's included a jewelled-gold presentation snuffbox by Morel of Paris with Ferdinand Philippe's monogram. It sold for £25,000.

* Subscribe to Country Life and save

* Follow Country Life magazine on Twitter

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.