Britain's political cartoonists: Speaking truth to power for 200 years

Cartoonists have been holding political figures to account since the Georgian era. Charles Harris retraces the history of a proud tradition of British satire.

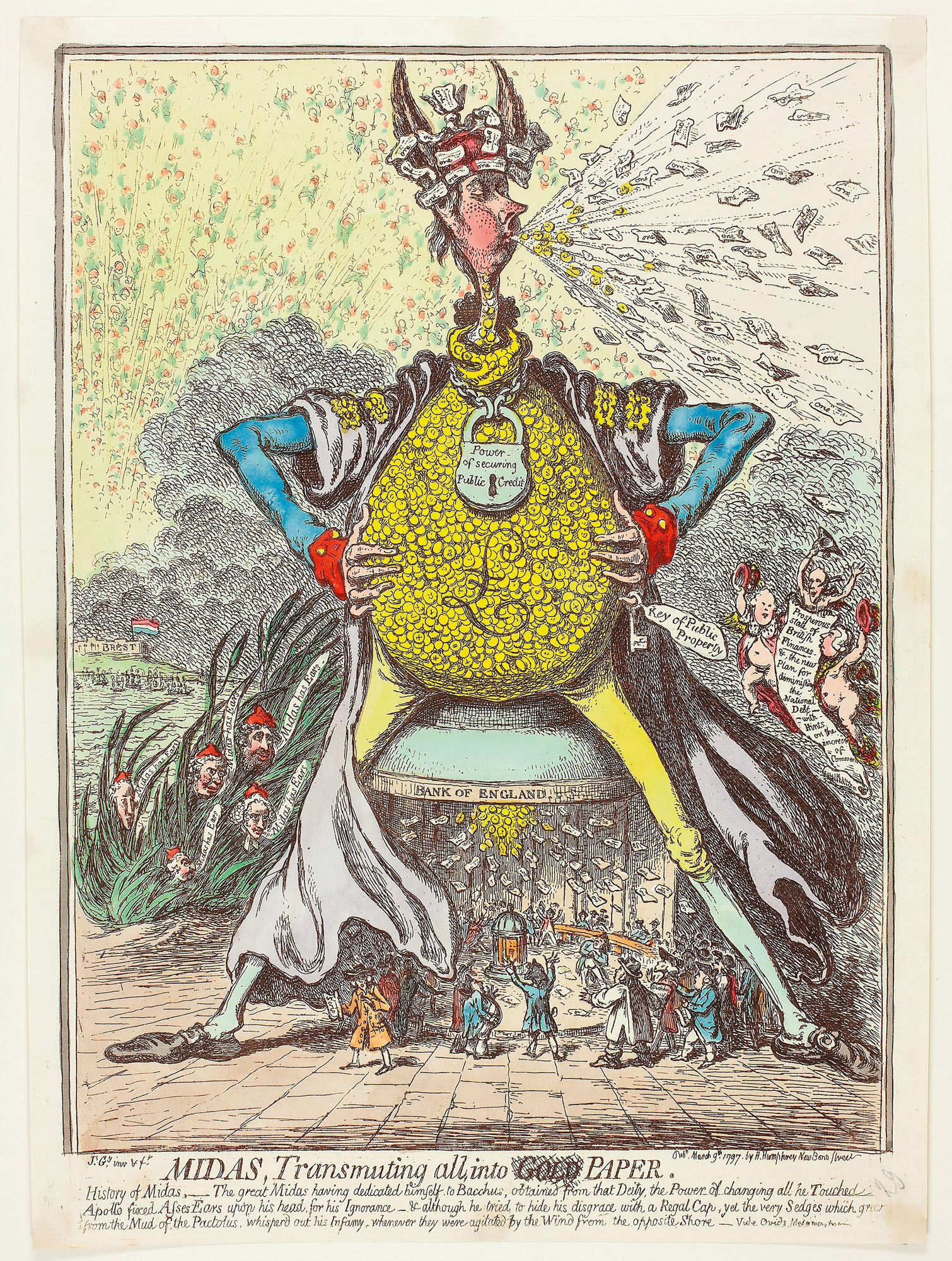

An article takes time to read, but a picture speaks to us instantly. In the 18th century, William Hogarth campaigned pictorially against idleness, cruelty and drink and Thomas Rowlandson invented comical strips. But it was after 1805, when James Gillray depicted a small, ravening Napoleon carving up the world with William Pitt, that the cartoon — a distillation of news, character and opinion — became a feature of English life.

The English tend to laugh at authority rather than rush to the barricades. Hypocrisy, dishonesty, and incompetence are all vulnerable. In unhappy lands where tyrants rule, cartoonists are suppressed, but here, they have thrived.

Napoleon once said that Gillray did him more damage than a dozen generals and ordered anti-English cartoons be drawn in retaliation. However, Gillray struck domestic targets, too, printing entertainingly rude colour pictures of the Prince of Wales — ‘a voluptuary under the horrors of digestion’ — and of Pitt, vomiting and excreting money in an early version of quantitative easing.

Punch cartoons — infrequently humorous and never scatological — dominated the 19th century. Elaborate allegorical caricatures — many by John Tenniel (illustrator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland) — alerted the nation, in anger or in awe, to significant events: a British Lion avenging the Indian Mutiny; society’s foolish ridicule of Darwin (often drawn as simian); Disraeli beguiling Queen Victoria with an Oriental crown. War clouds gathered, but Punch continued unchanged, as with Bernard Partridge’s 1914 German officer standing over a Belgian family he had shot.

Newspaper cartoonists adopted a lighter touch for grave times. New Zealander David Low — knighted, banned in Italy and Germany — drew simply. He sought to warn and arouse. His 1936 Adolf Hitler goose-stepped over the cringing Leaders of Democracy. Later, he drew Stalin and Hitler bowing reciprocally across prostrate Poland. Lord Halifax discouraged him from upsetting the Führer.

However, Low was later to upset the British, too, with a scrappy cartoon criticising the cost of the late Elizabeth II’s coronation. Churchill’s wartime portrayals were generally brave and indomitable, but he was saddened by Leslie Illingworth’s 1954 depiction in Punch of a spent old man. ‘There is malice in it,’ he repined.

The word ‘cartoon’, originally the preliminary sketch for a painting, acquired its modern usage in 1843 after a picture in Punch.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Far more amusing was Carl Giles, who arrived at the Daily Express in 1943. His approach, then and thereafter, was via a humorous focus on ordinary people. He created an extended family, with tiny children (‘squat and malignant’, according to Dennis Norden), gloomy adults, and a formidable Grandma — enigmatic, energetic and patriotic. Giles drew intricate backgrounds with clever perspectives, teeming with comical activity, in which regular characters — nurses, policemen, soldiers, schoolchildren, farmers, MPs — made droll remarks about current events, politicians and the Royal Family.

His draughtsmanship was astonishing. You can feel the rain, shiver in the snow, recognise the boats, cars and architecture. Called by Ronnie Corbett ‘that genius of the apt and topical’ and a prolific earner, Giles kept the nation cheerful and thoughtful for 50 years.

Another star soon joined him, operating in a radically different way with a compact, upper-class cast. This was Osbert Lancaster, inventor of the ‘pocket cartoon’, as well as being an architectural historian and theatrical designer. His small drawings (five a week for 40 years) were as sharp and elegant as his wit.

His world was fashionable London or the racecourse. His greatest character was Maudie Littlehampton, who once said: ‘Well, if Mrs Thatcher is the first woman Ted Heath’s ever found himself opposed to, it explains a lot.’ Lancaster excelled at oblique shots at government and foreigners, especially Arabs, and introduced us to Mademoiselle Gigi Pernod Framboise.

Where Giles and Lancaster spent the war in tolerable comfort, Ronald Searle almost died. In Japanese captivity after the surrender of Singapore, for more than three years he surreptitiously sketched the cruelty and starvation inflicted on Allied prisoners. This experience perhaps seared his soul. He invented what Max Beerbohm called the ‘Slaughterhouse of St Trinians’ and abandoned his wife and children.

Searle wrote: ‘It is not sufficient for a good cartoonist to be a competent artist with a sense of humour. He must enjoy a political prejudice that is narrow and strong… he must laugh public opinion into what he believes it should be.’ He drew an insincere-looking, juvenile Kennedy campaigning in 1960 and his Khrushchev was flaccid, coarse, but wily. He later drew eccentric pictures combining insight with hilarious absurdity.

According to Max Hastings, former editor of The Daily Telegraph and the Evening Standard, ‘every newspaper struggles to find good cartoonists’.

One whose cartoonish creation perhaps had the opposite effect to the intended was Victor Weisz, or Vicky. After Harold Macmillan replaced Anthony Eden, Vicky portrayed him derisively as Supermac, in Superman kit. Macmillan, who preferred tweed and had told everyone they had never had it so good, exploited this sobriquet and won the 1959 election handsomely. When Macmillan resigned after the Profumo affair, Trog (clarinettist Wally Fawkes) drew him retreating from a daubed wall slogan: ‘We’ve never had it so often.’ Vicky committed suicide in 1966.

An admirer of Searle was Gerald Scarfe, who worked for Private Eye and then the Sunday Times. He drew the Yes, Minister caricatures and displayed strong antipathy towards Margaret Thatcher, whom he depicted savagely, once as chewing John Major’s head off with reptilian teeth. He made Tony Blair a bat-eared ghoul, drew Bill Clinton at his desk with a nude girl crouched purposefully beneath the pedestals and was fond of depicting Donald Trump naked and pot-bellied. Scarfe is not perhaps everyone’s taste, but he and Gillray would understand each other perfectly.

Thatcher was not the only target for relentless visceral aggression. The Guardian’s Steve Bell liked portraying Michael Howard, a vigorous centre-right Tory leader, as emerging from graves, fanged, or drinking blood, after a junior minister said he had ‘something of the night’ about him.

Peter Brookes, who draws in a clear, firm style, is a little milder. He often transformed politicians into ingeniously grotesque wildlife — for example, Nicola Sturgeon and Alex Salmond as two fish eating each other — and regularly depicted Nick Clegg as the ‘fag’ of toffish David Cameron: ‘Cleggers, old son… halve the deficit before prep.’ Mr Brookes frequently targeted Boris Johnson, too. Especially vivid was Mr Johnson as a tipsy mendicant sitting on the steps of No 10 with wife and baby: ‘Give generously… Lulu Little interiors to support.’

Cartoons are able to take more risks than political journalists. For example, Jacob Rees Mogg, recumbent on a Brexit bus, stating: ‘Lying is my preferred position’.

Beyond people, lockdown proved a fecund subject for cartoons, involving unnecessary journeys, police insensitivity, ministerial uncertainty and restrictions on freedom, but, unlike the disease, they were rarely virulent.

Cartoons usually combine picture and caption, but one outstanding practitioner relies mostly on the words. His simple pictures take only minutes to draw and the captions are brilliant. Matt (Matthew Pritchett, with The Daily Telegraph since 1988) has the felicitous knack of putting ideas into illuminating juxtaposition.

When Gordon Brown was reluctant to leave No 10, Matt drew a woman in a Swiss-army-knife shop asking: ‘Is there something for removing a Prime Minister from Downing St?’ A child who has pulled down a snowman explains to his father: ‘I was worried that he might have historic links to the slave trade’; a Scottish announcement: ‘Two people may meet indoors to discuss Alex Salmond, but only if they forget about it afterwards.’

Indefatigably creative, Matt prepares six cartoons daily and, like Lancaster before him, reliably provides amusement for millions. But it’s amusement with a point, often a sharp point. Unlike some cartoonists, he enjoys the newsroom’s stimulus and observes that ‘a topical joke has the lifespan of a mayfly’.

Do political cartoons make a difference? They assist morale in war and, in normal times, a steady flow of derision — whether gentle, like Giles, or ferocious, like Gillray, Scarfe or Bell — presumably has some effect upon the minds of both voters and subjects, if only by osmosis. Thatcher’s strength, paradoxically, was probably partly forged by constant hostile depiction, but Sir John was clearly diminished by his external under- pants and Lib Dem MPs told reporters how worried they were about their leader appearing as the Prime Minister’s fag. Detractors of Jeremy Corbyn — usually given different-sized eyes — needed little help from cartoonists.

Mr Cameron considers that when a career is waxing, any cartoon may assist, when waning, they will harm; they are useful to indicate whether messages are getting through and often both anticipate and summarise written journalism. He believes English politics are tougher than most and that’s often reflected in virulent cartoons.

Mr Johnson has been relentlessly painted as hypocritical, mendacious and shifty — traits that outweighed the intellect beneath the crumpled carapace and infuriated his colleagues. Had he provided less ammunition, he might have lasted longer. In a more deferential age, he might have survived, as Lloyd George did.

Cartoonists don’t always find their task easy. Charles Moore, in his biography of Margaret Thatcher, recounts how Nicholas Garland, prolific for 30 years, said before he met her: ‘I just can’t do this.’ But, he did and, under his pen, she slowly changed from didactic to iconic.

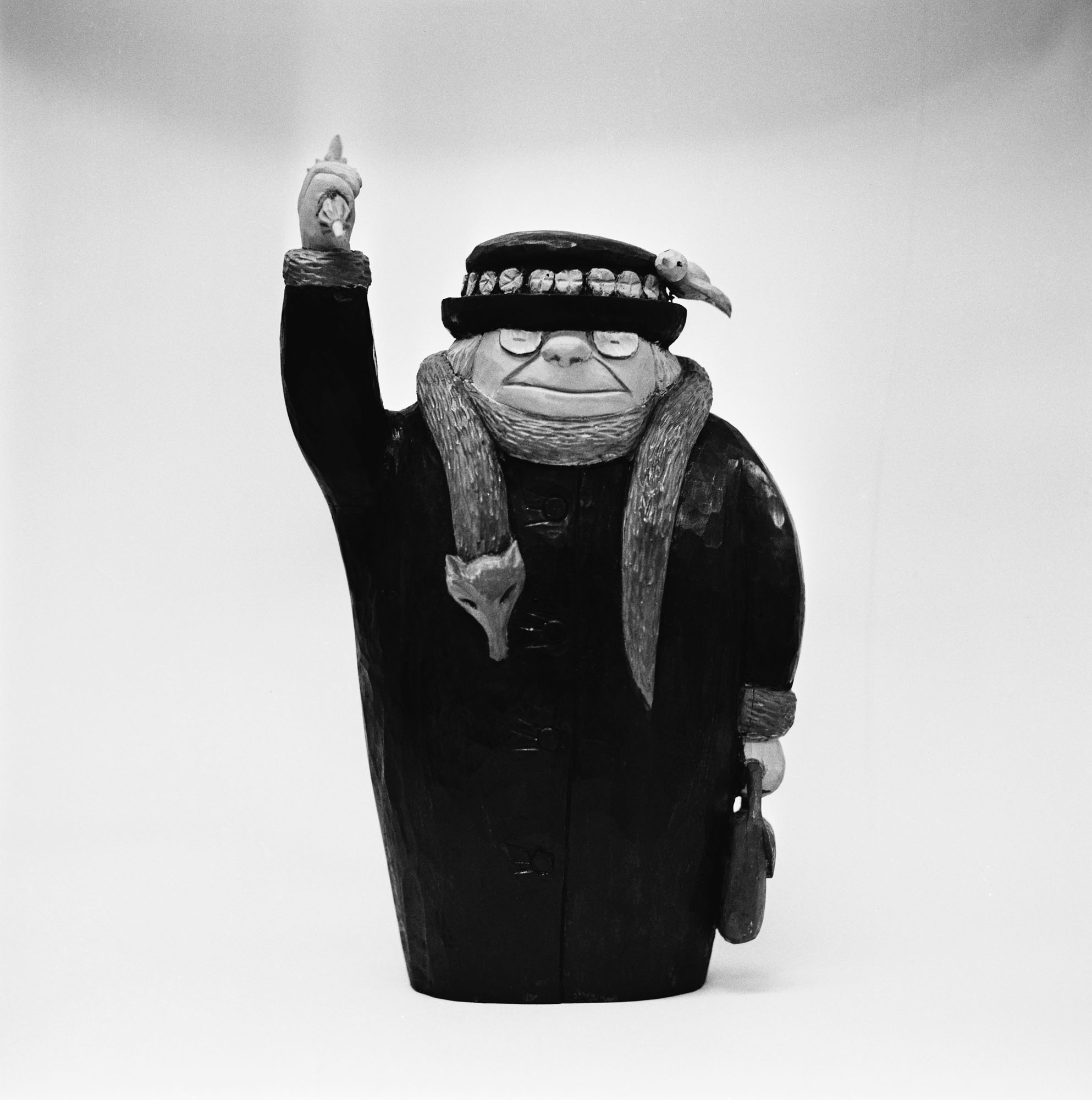

During the recent leadership contest, Liz Truss often appeared as a poor imitation of Thatcher and Rishi Sunak as wealthy and ambitious. These depictions were unlikely to prove determinative, unlike ITV’s Spitting Image, essentially animated cartoons with puppets by Peter Fluck and Roger Law that ran between 1984 and 1996. Watched by 15 million, Thatcher was dominant, Norman Tebbit a skinhead, Nigel Lawson unable to count and Neil Kinnock a windbag of unstoppable loquacity. David Steel was the puppet of David Owen — a precursor of Mr Clegg’s humiliation — and he alone felt his characterisation damaged him.

Finally, cartoonists may perform a panegyric role, as several did upon the death of the Queen. Here, they seek not to amuse or inflame, but to strike a spiritual chord, and to depict an unwritten epitaph upon a human life.

One thing is clear: English cartoonists have not succumbed to the tide of political correctness. They are back to Georgian vigour and we are lucky to have them.

The political cartoonist: 'Politicians hate how I depict them, but they'd hate it even more if I ignored them'

Peter Brookes, political cartoonist at The Times, is a savage commentator and the spiritual successor to the likes of Gillray

Charles Harris KC was a judge for 24 years and is the author of Trial and Error (a polemic and memoir). His interested include history, stalking, skiing, politics, mountain walking, architecture and travel. He has ridden in the Rockies, trekked in Bhutan and written on a wide variety of subjects — from national anthems to cartoons, aviation to art and sculpture, and occasionally law. He lives in North Oxfordshire with his wife Carol, and has three adult children and eight grandchildren.