Cutting it fine: the ancient art of wood engraving

The ancient art of wood engraving requires introspection and secrecy in order to create intriguing and intricate pieces of work, discovers Clive Aslet.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

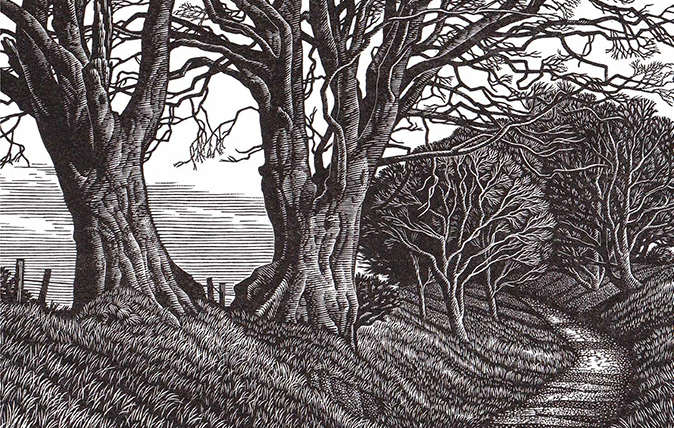

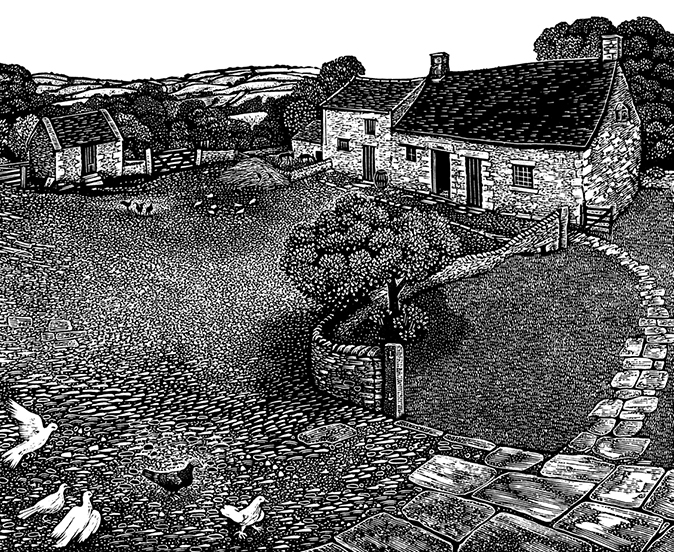

If you want an antidote to the computer screen, turn to wood engraving. ‘We’ve reached 1790, with dashes of the 1920s,’ discloses one practitioner, who would rather not be named for fear of incurring the wrath of other artists. This is an art, with a strong admixture of craft, in which it routinely takes days, if not weeks or months, to produce works of unassuming dimension—so small that they’re sometimes best appreciated with the help of a magnifying glass.

‘OCD,’ declares another exhibitor at the annual show by the Society of Wood Engravers (SWE), of the temperament required. ‘It’s ridiculous,’ admits Peter Lawrence, whose work is given pride of place as this year’s featured artist, of the amount of labour involved. ‘I like to include humour. That becomes difficult when you may be working on the same piece for 300 hours.’

For the collector, however, the obsessiveness of the artists yields a glorious reward. In relation to the amount of time spent in producing them, these modestly priced works—they rarely cost more than a few hundred pounds—are the steal of the century. Produced not in warehouse-sized studios, but often on kitchen tables, the works are intimate, if not always in subject, then in the mode of creation. This invites introspection, even secretiveness, and I’m told that artists are often astonished to discover what their peers have been working on and the methods involved.

For strangely, as the SWE exhibition, now touring the country, demonstrates, this ancient technique can be used to create of-the-moment effects. Some works are bold, even gritty. Every day, thousands of people pass the wood engravings that David Gentleman made for London Transport in 1978, which have been enlarged to platform scale.

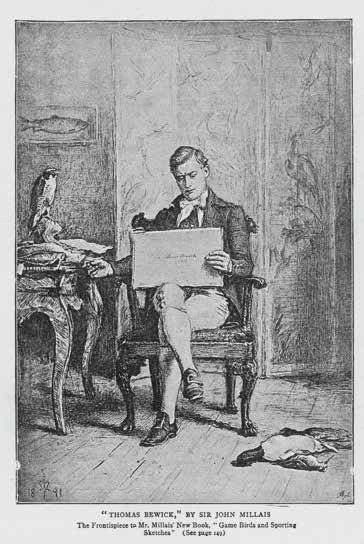

These much loved images of the building of the medieval Eleanor Cross—that is said (incorrectly) to have given Charing Cross its name—have an equivalent in Newcastle upon Tyne. To celebrate the 250th anniversary of Thomas Bewick’s birth in 2003, the Metro there commissioned a suite of wood engravings for its stations from Hilary Paynter (01237 479679; http://hilarypaynter.com). With the subject ‘from the Rivers to the Sea’, the artist was careful to include plenty of detail at the bottom of the panels to interest children as they wait for trains. However, these are exceptions. The natural condition of wood engraving is to be small. It opens a peephole into a private world.

Take out your spectacles. Like wildflowers, wood engravings are best seen up close. They invite contemplation. This medium is the antithesis of throwaway consumerism and internet-induced short attention spans. Its natural home is, to many people, the countryside—the British countryside at that.

Although the exhibition includes artists from as far away as Russia, China and Japan, wood engraving is still somewhat under the enchantment of Thomas Bewick, who effectively invented the technique in the late 18th century. Those closely observed little depictions of snipe and bulls, old oak trees and river scenes placed wood engraving firmly in the English pastoral tradition. There was a strong element of nostalgia to the revival that took place, under the hand of Eric Ravilious and others, in the early 20th century.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It can still be said that a medium that requires immense patience and a variety of extremely sharp, peculiarly named tools (spit-sticker, scorper) doesn’t produce front runners for the Turner Prize, but we live in a fallen age.

Let’s clear one thing up straight away. A wood engraving is not a woodcut, let alone a linocut. Lino can be worked like butter (or so wood engravers tell me), but although it lends itself to being printed in colour, it won’t take the same almost microscopically fine lines. Woodcuts are also relatively crude, because, as the block is taken from a vertical section of tree, the artist has to work around the grain.

The wood engraver works on the end grain, typically on a section of slow-growing box (sometimes lemon). As these trees don’t grow to a great size, the blocks that the engraver can use are necessarily small. Over the years, ways have been found of getting around this restriction. Sections can be joined together to form a larger block and it’s possible to find modern alternatives made from resin—indeed, certain types of kitchen worktop have been employed.

Even so, this is an artform in which people naturally think small—and in black and white. Which means, as Leonie Bradley (www.leoniebradley.com) tells me, ‘it’s all about the light’.

She shows me the studio that she shares with her husband, David Robertson, in a house overlooking Bath. It contains work benches and two old presses—one of them, a Victorian Hercules, being much as Caxton would have used. However, Leonie is as likely to work upstairs in the kitchen. Simplicity is part of the medium’s appeal. ‘All you need is a decent light and five tools and you’re away,’ she elaborates. ‘You can burnish a print from a block using the back of a spoon to press down the paper.’

This artform also requires a self-imposed discipline. Every wood engraver talks about the excitement of seeing light emerging from the darkness of the seemingly primordial block. Unlike etching or steel engraving, where each mark will be printed black, every gouge, scrape or dot made by the wood engraver comes out white—it’s the wood left behind that stays black.

Some artists disregard the obvious limitations and produce works that look as if they could be pencil sketches, although it will have taken hours of patient labour to isolate each seemingly spontaneous black line. for Leonie, the challenge is different. ‘Light and shadow are what really excite me. How do you achieve the dark grey tones?’ The answer is by many, many, many little lines and—as demonstrated by several artists in the show—an almost mesmerising level of skill, to which the word ‘virtuoso’ only does half justice.

It would be an outrageous stereotype to suggest that printing is a masculine activity, but it tends to be in the Bradley-Robertson household. David is by training an engineer and, in another life, worked on oil rigs. He has a natural affinity with the presses, as well as the Columbia and the Albion that Leonie’s mother, the wood engraver Hilary Paynter, has in Devon.

We won’t even mention inks. ‘They’re a whole world of their own. There are men who get very excited about inks.’

Arcane mysteries such as these may seem far removed from Leonie and David’s other interests—they’re both filmmakers. There is, however, a common theme: photography and films are equally dependent upon light.

Wood engraving is also a natural partner of the written word. Although art prints are now produced in limited editions, the hardness of the blocks also allows a huge volume of impressions to be made as required, hence the illustrations that adorn 19th-century periodicals such as The Illustrated London News, Punch and The Field. Now it’s more likely to be seen in conjunction with beautiful typography, perhaps printed by means of letterpress.

‘This is how books have been made since the Renaissance,’ explains Merlin Waterson, former regional director, East Anglia, of the National Trust, who took up wood engraving on his retirement a dozen years ago. He now makes powerful architectural studies, which are sometimes accompanied by his own texts, and David Gentleman recalls with affection the covers that he made for the ‘New Penguin Shakespeare’ editions in the 1970s. Long-standing readers of Country Life will remember the images of hares and fields by Howard Phipps that we commissioned in the 1990s. Phipps’s subjects are drawn from the Wiltshire countryside where he lives. ‘When I drove to his house,’ recalls Geri Waddington, chair of the SWE. ‘I thought, I’m in Howard Phipps country—I recognised the lanes.’

Appropriately, one of Geri’s own wood engravings in the show is of a waterwheel, to accompany a book on papermaking. Another shows a greenhouse at Great Dixter for a book on the garden created by Christopher Lloyd. Enough said. find the exhibition if you can and let it cast its spell.

For more details about wood engraving, contact the Society of Wood Engravers (01900 267765; www.woodengravers.co.uk). The SWE’s 79th annual exhibition runs from March 4 to 25 at the Zillah Bell Gallery in Kirkgate, near Thirsk, North Yorkshire (01845 522479; www.zillahbellgallery.co.uk)