Exhibition review: Art & Soul: Victorians and the Gothic

Michael Hall reviews a new exhibition celebrating Gothic romance in the West Country.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

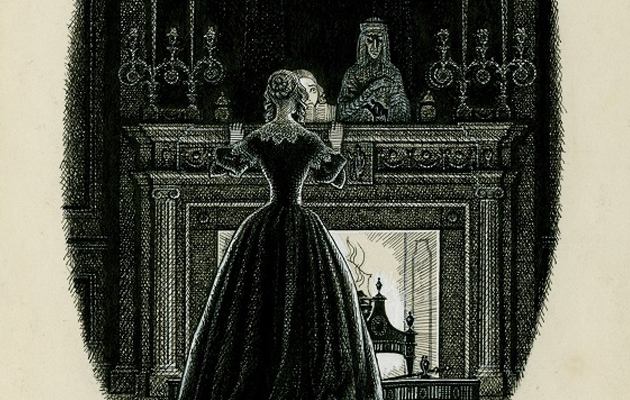

Glastonbury, Tintagel, even Camelot itself: from Somerset to Cornwall, the South-West of England is saturated in medieval romance. One result is a rich legacy of 19th-century architecture and design that has inspired a splendid exhibition at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter: ‘Art & Soul: Victorians and the Gothic’. Its setting could not be more appropriate: opened in 1868, the museum is a strikingly colourful High Victorian building, designed by Exeter’s leading Gothic Revival architect, John Hayward.

For anyone who hasn’t visited the city recently, the exhibition provides an opportunity to enjoy the results of the museum’s rec-ently completed decade-long campaign of restoration and exten- sion (saving it from threatened structural failure caused by the fact that it was built over the city’s Norman ditch). A group of designs and early views of Hayward’s remarkable building is included in the exhibition.

The curators, Joanne Parker and Corinna Wagner, both teach English at the University of Exeter and their broad cultural outlook has resulted in an exhibition that touches on a stimulating variety of themes in many media. They begin boldly with a large canvas, The Ruins of Glastonbury Abbey from the Museum of Somerset in Taunton. Painted by George Arnald in about 1810, it sums up in a single image why the South-West inspired so many antiquaries, novelists and poets, as well as architects and designers, from the late 18th century onwards.

The opening gallery offers an instructive survey of the Gothic Revival in England from early-19th-century romanticism to the death of Prince Albert. A. W. N. Pugin is represented by his books, together with a well-chosen sel-ection of his metalwork made by Hardman of Birmingham, and Ruskin’s influence is demonstrated by beautiful examples of his water-colours and drawings of Gothic buildings in Italy.

Strong and challenging claims are made for the impact of Gothic on the image of the British state. As well as a view of Charles Barry and Pugin’s new Palace of Westminster, the curators have included the famous painting by Landseer from the Royal Collection depicting Queen Victoria and Prince Albert dressed as Queen Philippa and Edward III for the medieval bal costumé at Buckingham Palace in 1842, arguing that the monarchy strengthened itself by drawing on medieval imagery.

However, Albert and Victoria showed no interest in Gothic or medievalism for their architectural commissions, apart from the special case of Balmoral. The Queen’s dislike of the High Churchmanship with which Gothic was associated for much of the century must surely have played a part in that lack of enthusiasm.

The second and larger of the two galleries in which the exhibition is shown presents an impressively wide-ranging display of the Gothic Revival in the South-West. It encom-passes domestic and institutional design as well as ecclesiastical a watercolour of a Norman pumping station near St David’s station, Exeter, built in about 1856, perfectly demonstrates how the Victorians fused medieval styles with modern purposes.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Domestic Gothic is encompassed by loans from two National Trust houses, Tyntesfield in Somerset and Knightshayes in Devon, including a selection of William Burges’s spectacular (but only partly executed) designs for the interiors of the latter. Burges who, in 1874, designed the chain of office for the Mayor of Exeter (on show here when not in use) would have been delighted by the most extraordinary object in the room, the bronze-and-crystal throne from Tyntesfield made by Barkentin & Krall in 1877 following a published design by the great French Gothic Revi val architect Viollet-le-Duc.

The display of church furnishings includes all the major media: an 1862 stained-glass window by Clayton & Bell from St David’s, Exeter; a large and unattributed brass lectern from St Mary, East Teignmouth; a design by Burlison and Grylls for a window in Exeter Cathe-dral, 1872; and a mighty wooden font cover designed by W. D. Caröe for St Andrew, Paignton, in 1912.

There is also an intriguing selection from the museum’s collection of fragments of medieval wood carving accumulated by one of the country’s most prolific Victorian architectural sculptors, Harry Hems, who moved to Exeter from London in the late 1860s as a result of being emp-loyed to work on the museum.

Although they make a striking display, none of the Victorian church furnishings is of exceptional quality, but that cannot be said of the fine selection of exhibits demonstrating the impact of medievalism on the Arts-and-Crafts Movement, culminating in the first tapestry from William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones’s great series depicting the quest for the Holy Grail, woven in 1898–9.

With it, one might have exp-ected to see work by that most influential Arts-and-Crafts Gothic architect and designer J. D. Sedding, whose work is so richly represented in the South-West, but oddly merits no mention in either the exhibition or accompanying book. Instead, the curators have enterprisingly chosen to focus on W. R. Lethaby, bec-ause he was born in Barnstaple.

Together with some well-known objects, including his sideboard made for Melsetter House in Orkney, they have borrowed from the Museum of Barnstaple & North Devon a wonderfully sensitive pencil drawing of 1879, Old House at Exeter, a reminder of how the city’s architectural legacy from the Middle Ages has inspired artists and designers through- out the centuries.

‘Art & Soul: Victorians and the Gothic’ is at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery, Exeter, Devon, until April 12, 2015 (01392 265858; www.rammuseum.org.uk)

Exhibition review: Impression soleil levant at Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Huon Mallalieu reviews an exhibition dedicated to the origins of Impressionism.

Exhibition review: William Blake at the Ashmolean, Oxford

Martin Gayford reviews William Blake at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

The best art exhibitions to visit this December

Read our comprehensive list of the best art exhibitions around the country to visit this December.

Exhibition review: Rossetti’s Obsession

Averil King relishes a show spotlighting a famous love triangle.