In Focus: How Christina Rossetti's poetry spilled over into the world of art

One of our great Victorian poets had an impact far beyond the words she committed to paper. Jeremy Musson takes a look at a new exhibition looking at Christina Rossetti's influence on the world of art.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

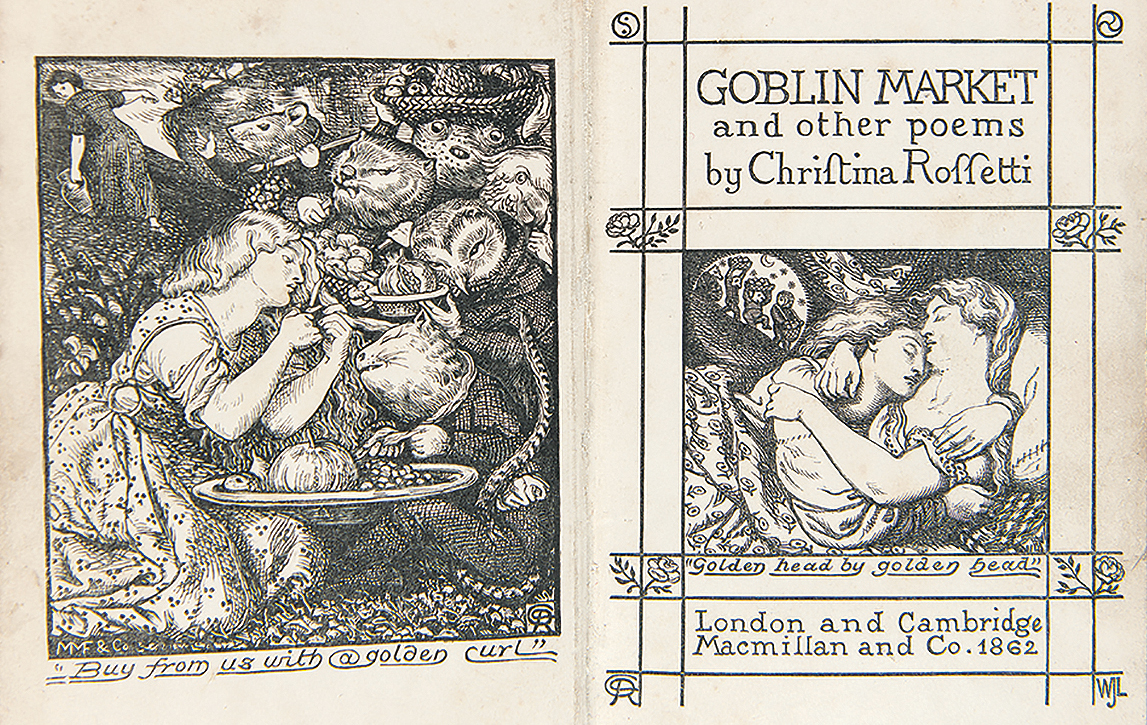

The Victorian poet Christina Rossetti is especially remembered for In the Bleak Midwinter, the verses of which were set to music by Holst in 1906 and rearranged in an anthem setting by Harold Darke (it was named as choral experts’ favourite carol in 2008). Her Goblin Market and Other Poems (1862) was a considerable success and her poems were widely read during her lifetime, as well as influencing many later poets.

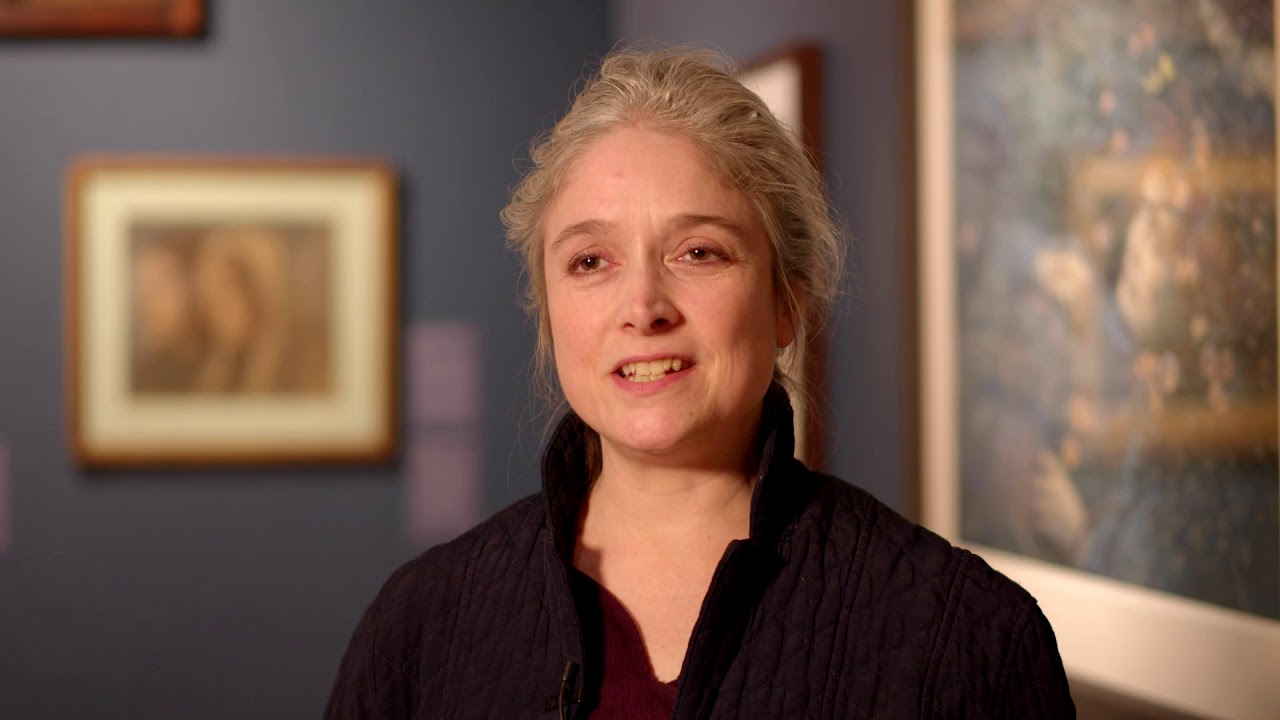

Yet words were just part of her artistic talent, and some of her different gifts are currently being celebrated by the Watts Gallery in an exhibition that is the first to be devoted to Rossetti’s interest in, and influence on, the world of visual art. Co-curated by Dr Susan Owens and Nicholas Tromans, Christina Rossetti: Vision & Verse – running at the gallery just outside Guildford until March 17 – brings together paintings inspired by her poems, as well as published and unpublished illustrations.

Christina was born in London into the highbrow Anglo-Italian Rossetti family: her father, Gabriele, a poet and political exile, her mother, Frances, also a poet, and their children, who all forged reputations as artists and writers. Christina’s brother Gabriel, known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was a founder of the group that called itself the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and went on to revolutionise British art.

Christina, who was engaged for a time to James Collinson, one of the Brotherhood, and who served as both muse and model to many of its artists, once referred to her ‘double sisterhood’ with the group. Her relationship with other key women in this Pre-Raphaelite story, such as Lizzie Siddall or Fanny Cornforth, is, perhaps surprisingly, not explored in the show.

However, this small and carefully composed exhibition gives a vivid insight into the mid-Victorian creative world and shows how the crafted simplicity and directness of Christina’s poetry reflects something of the early Pre-Raphaelite ideals. Her poetry occupied the same vivid dreamscape as their paintings, with a shared simplicity of expression, attachment to truth in Nature and emotional intensity illuminating both art and words. Yet whereas Gabriel was famously anti-clerical, his sister was a spiritual person, devoted to the High Church Catholic Revival of the Anglican Church.

The show explores the unfolding image of Christina as poet. Early intimate sketches by Gabriel, dating from the 1840s, are succeeded by a brilliantly intense, jewel-like, if unfinished, 1857 portrait by John Brett, with Christina’s face partly framed by a study of a feather. An 1866 coloured-chalk image presents the mature poet, drawn shortly after the publication of her second anthology, The Prince’s Progress and Other Poems, that year.

Christina also studied art herself, attending the North London Drawing School in the early 1850s. Some of her sketches are included in the show, alongside later drawings prepared as guides for illustrators working on her books of poems for children.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Late in her life, G. F. Watts approached her with a wish to include her in his ‘Hall of Fame’ series, but she was too ill to sit, so was never painted.

Christina spent her early adulthood modelling for painters of the Pre-Raphaelite Brother-hood; she also made her own contribution to the movement by writing poetry for its short-lived journal The Germ, edited by her brother William.

An early pencil sketch in the show depicts her as a vulnerable young Virgin Mary, startled, almost cowed by the presence of the Archangel, an image that Gabriel went on to realise fully in the oil painting Ecce Ancilla Domini (1850), which now hangs in Tate Britain.

Gabriel and John Everett Millais provided illustrations for Goblin Market and The Prince’s Progress in the 1860s. The exhibition also includes illustrations to Rossetti’s poetry by Arthur Hughes and Frederick Sandys. After the 1860s, works of art inspired by her poems, such as Arthur Hughes’s The Mower (1865), began to appear at London exhibitions.

Art photography pioneer Julia Margaret Cameron based her composition The Minstrel Group (1866) on a line from a Rossetti poem; from the 1890s, painter John Byam Shaw regularly used passages from her work.

A highlight of the show (and pictured at the top of this page) is Henry Treffry Dunn’s watercolour of the sitting room of Gabriel’s Chelsea home, Tudor House, depicting the painter and his friend, Theodore Watts-Dunton, seated in the room (it was painted after Gabriel’s death in 1882, as a record). Within the painting are two pictures on the far wall that, at first glance, might be taken as engravings of Renaissance saints. In fact, they are a portrait of Christina and a double portrait of her and her mother, both drawn by Gabriel in 1877.

Perhaps the most surprising and memorable object in the exhibition is a reredos designed as a memorial to Christina by Burne-Jones. Executed by his pupil Thomas Rooke, it depicts the Risen Christ with the four Evangelists standing against a richly patterned gold cloth.

It was presented to Christ Church, Woburn Square, London WC1, where Christina worshipped for many years (the church was demolished in 1974 and the reredos now resides in All Saint’s, Margaret Street, W1).

The object underlines the respect in which the poet was held and connects the narrative of this intriguing exhibition to the piety that was at the centre of Christina Rossetti’s artistic life and thought.

‘Christina Rossetti: Vision & Verse’ is running at the Watts Gallery just in Compton, just outside Guildford, until March 17 - see www.wattsgallery.org.uk. The exhibition is accompanied by a new book edited by the curators and published by Yale, ‘Christina Rossetti: Poetry in Art’.

Rossetti, pre the Pre-Raphaelites, drawings by the teenage Dante Gabriel Rossetti dating from 1844 to 1848, is at Wightwick Manor, Wolverhampton, March 1–December 24 – www.nationaltrust.org.uk/wightwick-manor

Credit: Bridgeman

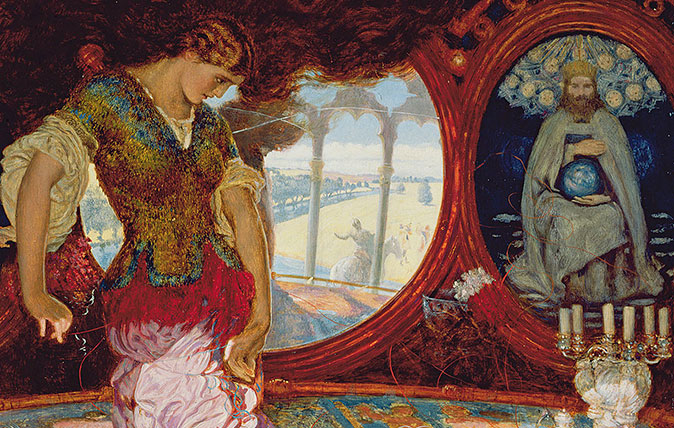

In Focus: How Holman Hunt's Lady of Shallot was inspired by Van Eyck's greatest masterpiece

Holman Hunt was one of several pre-Raphaelites inspired by Jan Van Eyck's iconic The Arnolfini Portrait. Lilias Wigan takes an

In Focus: The ancient roman temple which lay under London, undiscovered for over 17 centuries.

The temple of Mithras has been beautifully restored by Bloomburg SPACE and now sits under their Headquarters by Bank tube

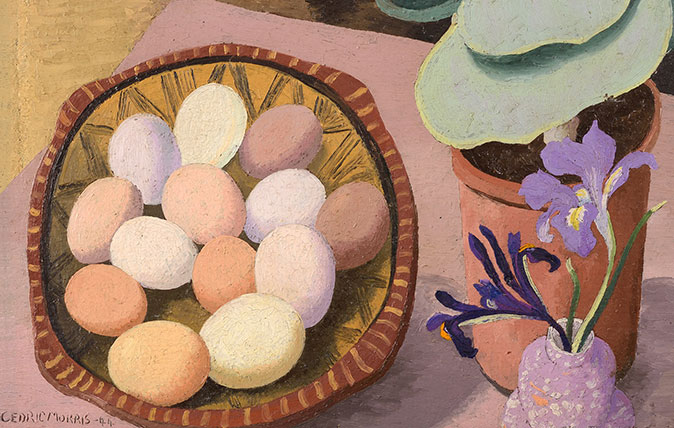

In Focus: The plantsman-turned-artist who found art in flowers, and painted from corner to corner

Cedric Morris's striking still life images have been largely forgotten for three decades, but three new shows are ending that

In Focus: The 160-year-old ‘Photoshopped’ picture which shocked Victorian England

An exhibition looking at four of the giants of Victorian photography has at its centre a remarkable work by the

In Focus: Leonora Carrington's extraordinary portrayal of Max Ernst, the surrealist pioneer who inspired Dalí

A stunning portrait of Max Ernst, one of the key figures in 20th century art, is at the heart of