In Focus: The stunning collection of philanthropist Samuel Courtald, including Cézanne's most groundbreaking works

Courtald's collection of Impressionist works returns to The National Gallery for the first time in 70 years. Chloe-Jane Good takes a look.

In September this year, The Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House in London closed its doors, for two years at least, to make way for a £50m refurbishment. It is predicted that the refreshed gallery spaces and updated facilities will nearly double annual visitor numbers.

Over the course of its closure, works from The Courtauld Collection will go on loan to national and international institutions, including The National Gallery, London, Ulster Museum, Belfast and Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris.

On exhibition now, at the National Gallery until 20 January 2019, is Courtauld Impressionists: From Manet to Cézanne, comprising the Courtauld’s Impressionist and Post-Impressionist masterworks and a selection from the National Gallery’s own Impressionist collection.

For the most part, the works in the exhibition coming from the National Gallery’s collection were acquired and gifted to the nation in the 1920s by the Samuel Courtauld Fund, founded by businessman and philanthropist, Courtauld himself (1876-1947).

Upon setting up the Fund in 1923, a committee was appointed to research and select modern French art for the British public but, ultimately, the greatest influence was Courtauld’s, which is not surprising, as the passion was his and it was he who financed the entire project, a munificent gift in the 1920s amounting to more than £50k.

This is the first time in London in 70 years that the National Gallery is exhibiting major Impressionist works from the Courtauld and thus it is a special occasion to see these 26 paintings, so cherished by Courtauld at his home on Portman Square in London, and later to be bequeathed to the Courtauld Gallery, now united with those he brought together for the nation.

From 1860-1886, ’the true Impressionist years’, as Sue Roe, author of The Private Lives of the Impressionists (2006) calls them, the young French painters gathered predominantly in Paris or in the countryside nearby. They painted together and supported each other as artists, through the disappointment at the little recognition they received, continued rejection, even ridicule and deep financial struggle.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Their paintings were mostly rejected by the prestigious annual Paris Salon and even by the Salon des Refusés, set up to exhibit works rejected by the Salon.

Ironically, what marks the end of the essential Impressionist years, was the major successful exhibition of 300 Impressionist works at the American Art Association in Madison Square, New York, in 1886, organised by French dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel. Shortly after the exhibition, the group dispersed and, for some, including Paul Cézanne, almost total isolation followed.

Up to 1917, Britain refused to recognise modern Continental painting. In 1905 an offer of a painting by Claude Monet was turned down by the National Gallery but in 1917 it staged an exhibition of Impressionist works from the collection of the late Irish dealer, Sir Hugh Lane. Courtauld saw this show and his love of modern French painting began.

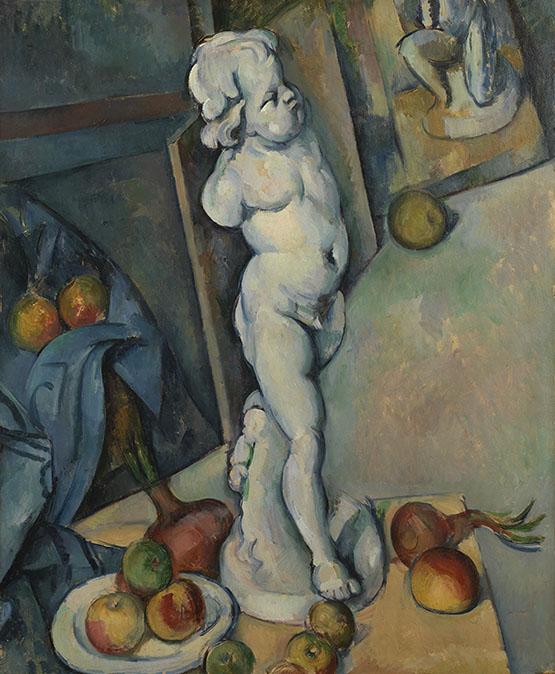

Among Courtauld’s most treasured works from his personal collection were those by Cézanne, and in particular, the groundbreaking Still Life with Plaster Cupid (c.1894) now on exhibition at the National Gallery.

It overthrows formalities of still life painting by abandoning the conventional landscape format for portrait, skewing perspective in various directions, mixing spatial planes and blurring reality with illusion.

The blue drapery depicted on the stacked canvas on the left of the painting flows out of the picture ground into the room, the table (or is it the floor?) rises up dramatically to the right as an apple sits comfortably on its tipped edge.

The plaster cupid, instead of short and plump, has elongated legs which twist one way while the torso twists the other. Gravity, perspective and volume, as we know them, are blown apart.

In an earlier painting by Cezanne, Pot of Primroses and Fruit (c.1888-90), also in the exhibition, we see signs of the cupid still life to come. Strong lines of a canvas stretcher lean against the table behind the plant and fruit muddling perspective and our expectations of still life.

Even today, the cupid painting has a shaking and compelling effect. In 2007, Richard Serra, in an interview for the catalogue accompanying his exhibition, Sculpture: Forty Years, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, recalls the moment he saw it for the first time: ‘…the hair on the back of my neck stood up…There are moments where as a viewer you feel challenged – you realise that someone has extended their vision in such a way that if you are going to make any contribution at all, you have to break new ground’.

'Courtauld Impressionists: From Manet to Cézanne' is on display at The National Gallery London in The Wohl Galleries until 20th January 2019. See The National Gallery website for more details.

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

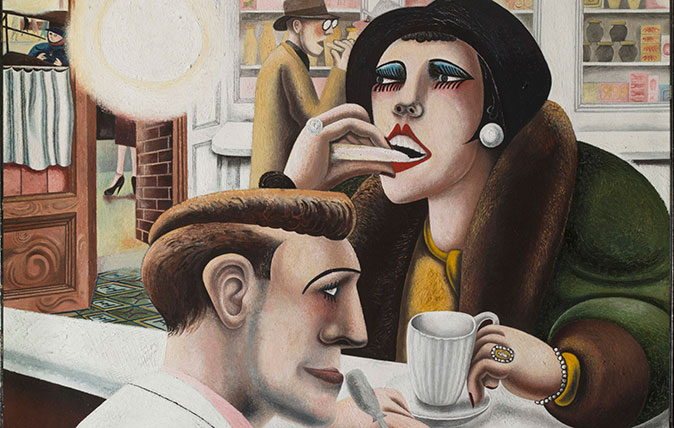

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack

In Focus: The ancient roman temple which lay under London, undiscovered for over 17 centuries.

The temple of Mithras has been beautifully restored by Bloomburg SPACE and now sits under their Headquarters by Bank tube

Credit: Getty

In Focus: The hand-drawn maps from which JRR Tolkien launched Middle-earth

'I wisely started with a map and made the story fit,' JRR Tolkien once wrote. A new exhibition in Oxford

Credit: ©David Hurn / Magnum Photos