In Focus: A self-portrait by Gaugin which fuses the real and the imaginary in a picture of narcissism and divine comparison

Lilias Wigan analyses Gaugin's 'Christ in the Garden of Olives', commenting on the painter's propensity to focus on himself, understanding the world purely as it could be viewed through his own eyes.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Having surrendered his Paris city job to pursue a career as a professional artist, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) moved to Pont Aven, Brittany. By this time (1886), his relationship with his wife Mette was fraught and she had already moved back to her native Copenhagen with their children. Penniless and unaccompanied, Gauguin sought out Pont-Aven’s low-cost living, with its established artistic community.

He returned to Brittany a number of times and it was during his third stay, in 1889, that he produced Christ in the Garden of Olives, currently on view in London at the National Gallery’s The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Gauguin Portraits. Gauguin adopted various facades in his self-portraits and this particular painting epitomizes one of his favourite analogies — that between his own creative suffering and the agony of Christ. Albrecht Durer had famously done this in his Self-portrait (1500), but, whereas Durer explored the theme of artist as semi-divine creator, Gauguin’s comparison was between Christ’s anguish and his own.

‘The lack of encouragement, all scourge one with thorns’.

Christ in the Garden of Olives shows the artist as Christ on the eve of his betrayal. With striking red hair and mask-like face, he stoops in the corner at the forefront of the composition, while behind, in an imagined, exotic landscape blending themes of religion, fable, myth and local traditions, ominous figures seem to flee from the subject. The protagonist, cast as a martyr, is instantly recognisable by his profiled hooked nose and heavy eyelids. The central tree trunk divides the composition like a diptych, further isolating the Christ figure from his compatriots and reminiscent of the Cross.

Gauguin chose the familiar biblical iconography as a subject that his viewers would relate to, using the symbolic and spiritual to communicate his own suffering to greatest effect. In this, he defied the conventions of orthodox European portraiture, which was intended principally to convey a sitter’s persona or social status. His experimental work was often met with incomprehension during his lifetime, which, together with his lack of commercial success, instilled a sense of persecution, evident not only in his art, but also in his writings: ‘The lack of encouragement, all scourge one with thorns’.

‘I walk about like a savage, with long hair… I have cut myself a few spears and, like Buffalo Bill, practise spear-throwing on the beach. That then is he, whom they call Jesus Christ.’

Narcissistic by nature, Gauguin focused on himself in both his art and his writing throughout his career and strongly believed that the world could only be understood from such a personal vision. He projected himself as an artist who suffered for the benefit of his art and also wanted to be affiliated with non-European cultures. This practice of self-mythologizing is clear in a letter sent to the French painter Émile Bernard in in 1890: ‘I walk about like a savage, with long hair… I have cut myself a few spears and, like Buffalo Bill, practise spear-throwing on the beach. That then is he, whom they call Jesus Christ.’

By fusing the real and the imaginary with such determination and self-confidence, Gauguin expanded the potential of portraiture into unexplored territory.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Exhibition review: Maggi Hambling: Walls of Water at the National Gallery

Lilias Wigan reviews an exhibition by the National Gallery’s first artist in residence.

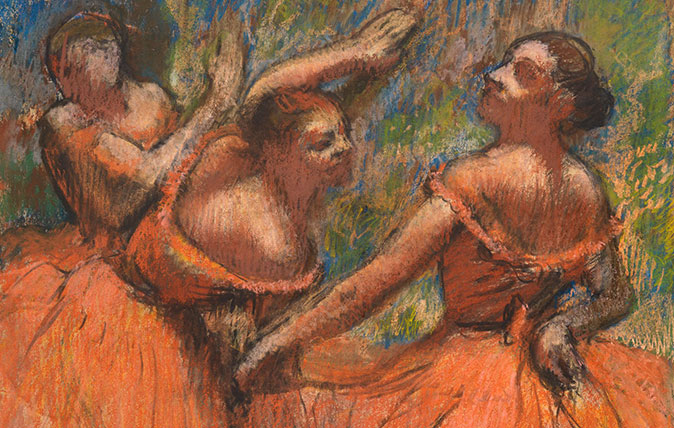

Credit: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas - The Burrell Collection, Glasgow © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

In Focus: The Degas painting full of life, movement and 'orgies of colour'

Lilias Wigan takes a closer look at one of the key work's at the Degas exhibition at the National Gallery

Credit: Michael Armitage, The Flaying of Marsyas, 2017. © Michael Armitage. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby). Courtesy of the Artist and White Cube.

In Focus: Michael Armitage's image of African violence that points the finger back at the western world

Michael Armitage's The Flaying of Marsyas is the centrepiece of his exhibition in South London. Lilias Wigan examines it in

In Focus: The Bald Eagle, America's symbol, 'torn apart, deranged and fragmented' by Lee Krasner

Lee Krasner's bold work is the subject of an exhibition at The Barbican. Lilias Wigan paid a visit, and focuses

In Focus: How Pierre Bonnard used photography to help him paint pictures that would once have been near-impossible

The mysterious French artist Pierre Bonnard is the focus of a new exhibition at Tate Modern. Lilias Wigan went along.

In Focus: The Norman Ackroyd landscape etchings that have sparked comparisons with Turner

This week marks the last chance to see Norman Ackroyd's sublime exhibition in Richmond. Lilias Wigan urges you to take