In Focus: The £20 million Michelangelo sketch that's one of just 10 in private hands

Business was booming in the world capital of drawing, headed by the sale of a Michelangelo. Huon Mallalieu takes a look.

Paris was the world capital of drawing for one week last month. It was frustrating to have only two days, with so much on offer: superb exhibitions, including the Louvre’s drawings owned by Giorgio Vasari, the founder of art history, and ‘True to Nature: Open Air Painting 1780–1870’ at the Fondation Custodia, which demonstrates that oil sketches can be close kin to drawing. At the centre were the Salon du Dessin at the Palais Brongniart and Drawing Now, the contemporary fair in the Carreau du Temple.

I was happy to stay at the Drawing Hotel, opened in 2017 in the rue de Richelieu by Drawing Now’s founder Christine Phal. She and her daughter, Carine Tissot, run the Drawing Lab there, offering four exhibitions a year, as well as space, equipment and support for anyone to drop in and draw.

The week also saw the sale of probably the most distinguished drawing that Christie’s will have to offer for many a year. Michelangelo’s 13in by 8in brown-ink-and-wash Nude Man (after Masaccio) had been subject to an export stop by the French government, which lapsed in time for the sale to coincide with the Semaine du Dessin. Perhaps 10 of the artist’s drawings are still in private hands and this was his first known nude, produced when Michelangelo was honing his skills by drawing from Masaccio’s frescos in the Brancacci Chapel, Florence, Italy. It is not exactly a copy, as he enhanced the physique of the shivering man newly emerged from baptism.

When sold in 1907 it was regarded as ‘school of’. It then belonged to the pianist Alfred Cortôt (1877–1962), and only in 2019 was it authenticated, by then Christie’s specialist Furio Rinaldi. In the event, it was bid to €23,162,000 (£20m), having been estimated to €30 million.

Nothing in that league was at the Salon, but the opening was bustling with connoisseurs joyful to be there. Business was being done, although, I suspect, judiciously.

A tradition at the Salon is a loan exhibition to publicise particular museum collections. This year’s was advance notice for one that has yet to open, the Musée du Grand Siècle, which will occupy an old barracks at Saint-Cloud from 2026. The drawings on show were a tiny portion of a magnificent gift of 673 paintings, 3,502 drawings and 603 Venetian glass animal figures collected by Pierre Rosenberg, art historian and former director of the Louvre. What an eye, and what luck, he has. I was most taken by a black-and-red pastel head of a man by Federico Barocci (1535–1612), which gave a powerful impression of character. Barocci divided his painting career between his native Urbino and Rome and pioneered the use of pastel, especially for heads such as this and for studies of cats.

Here, I illustrate some of my favourite offerings on the stands, whether sold or not. A later artist who made a formative visit to Rome was Théodore Géricault (1791–1824), who travelled in Italy during 1816 and 1817. In Rome, he concentrated on classical sculptures of men and horses, and he planned an ambitious painting of a horse race in the streets. Like many of his projects, it was never completed, but studies such as the 7¼in by 10in sheet of male figures (Fig 2), including Laocoon and horses, with Arnoldi-Livie of Munich, are connected to it.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In his last years, Géricault made studies of severed heads and limbs. With Maurizio Nobile of Milan there was a similar subject by a contemporary, a drawing of a condemned man by Giuseppe Diotti (1779–1846). Later, Diotti made a before-and-after double study of the head.

Always on the lookout for work by Léon Spilliaert (1881–1946), I found two with the Lancz Gallery of Brussels. A watercolour of two women seated in a park made me laugh, but the 10½in by 15½in Arbres au levant 1946 in ink and watercolour was matter for a sigh. Rather than Spilliaert’s hallmark eeriness, this was a poignant, perhaps last, observation of the dawn through trees.

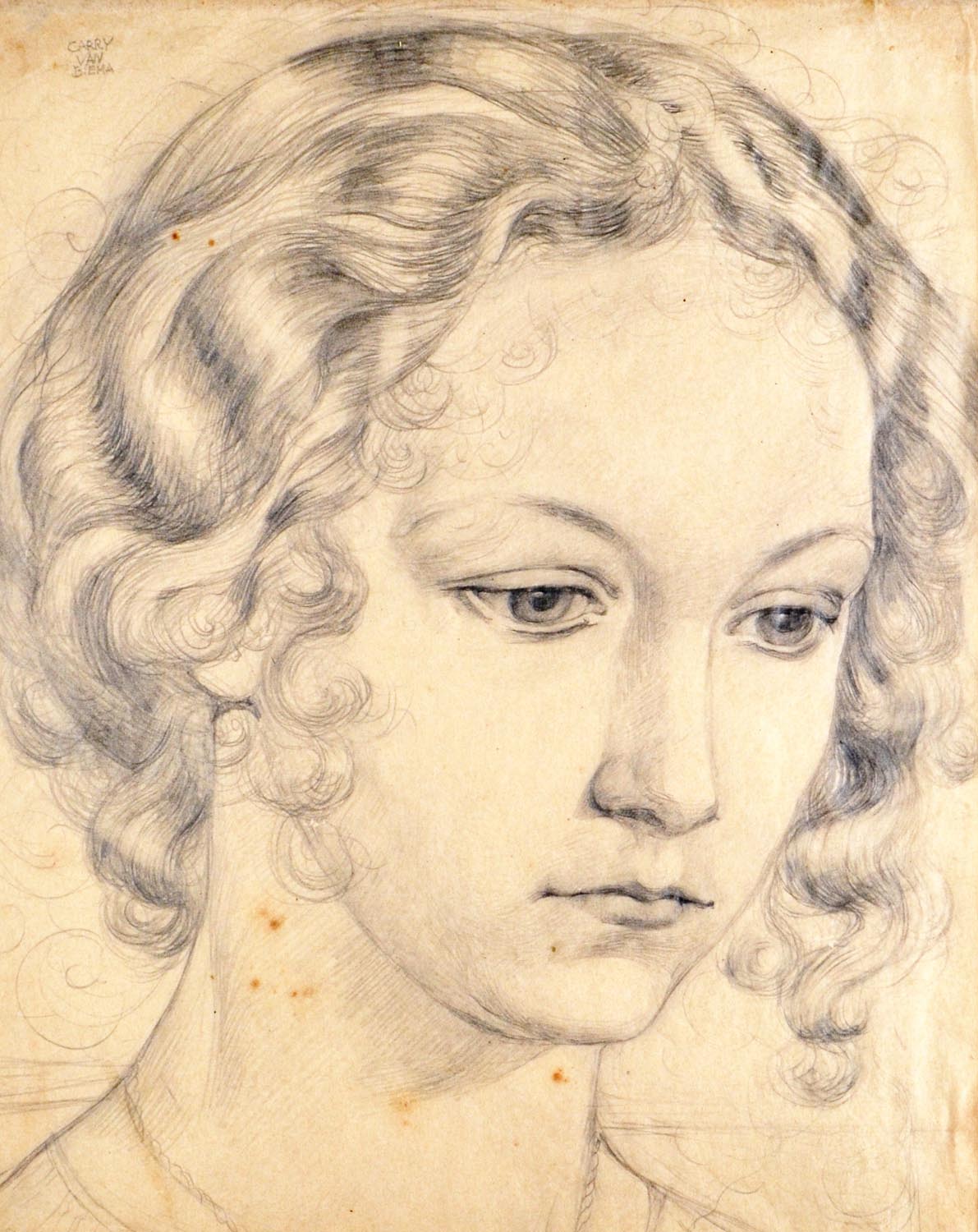

There was poignancy, too, in a 11in by 9in pencil head of a young girl (Fig 3) by the Dutch-German Carry van Biema (1881–1942). A teacher and author of a now-rare book on colours, her promising career ended at Auschwitz. In the 1930s, she had worked in Barcelona and the drawing was with De La Mano of Madrid.

Sunniness rather than melancholy characterised the 15½in by 13¾in harbour scene (Fig 4) in distemper on paper of 1908 by Edouard Vuillard (1868–1940), shown by Jill Newhouse of New York.

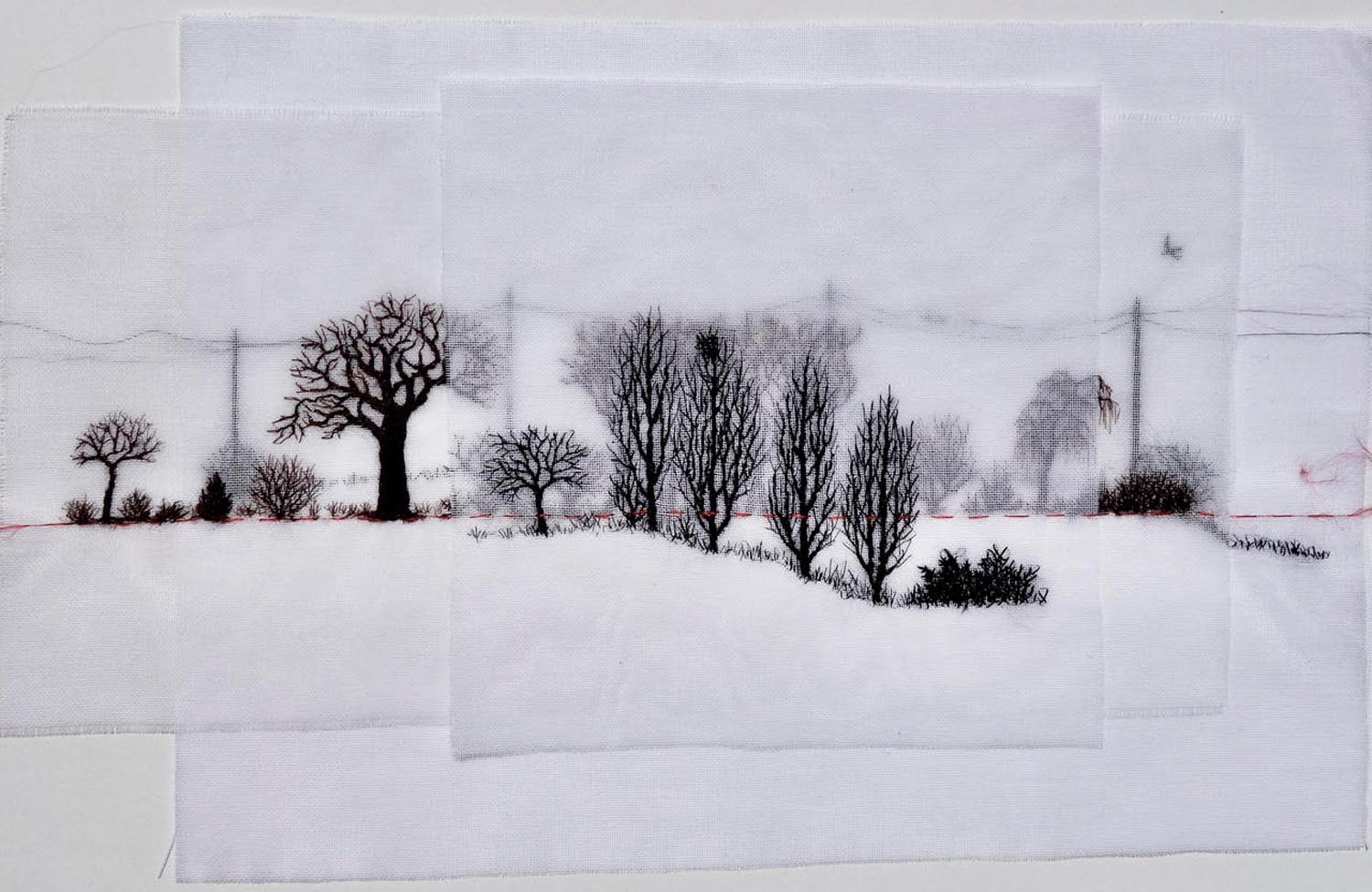

The opening of Drawing Now also bustled—I saw two major deals being concluded at the same time on one stand. This is the fair at which to find emerging talent and to discover new ways of drawing. I was intrigued by the 5in by 8in Lointains (Fig 5) by Frédérique Petit (Galerie Valérie Delaunay), who ‘draws’ in thread sewn on silk, and by Marie Havel (Galerie Jean-Louis Ramand) who uses flocking on card.

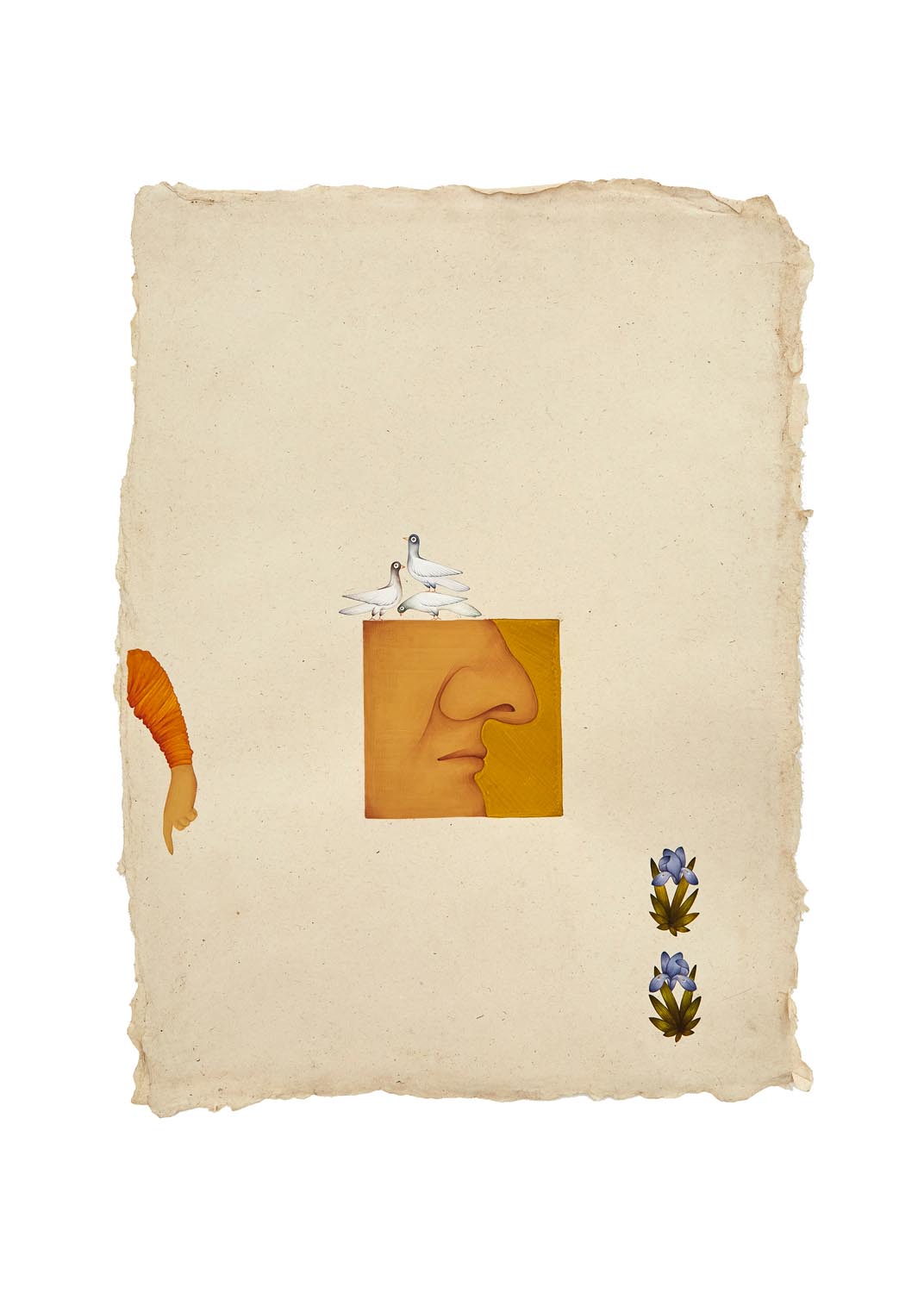

A fusion of traditions, as in Laila Tara H’s 19½in by 14in Neophyte 1 (Fig 6) in natural pigment and watercolour on Indian hemp paper, derives from Indo-Persian miniatures (Purdy Hicks Gallery).

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.