In Focus: The fine art of cloisonné, the 'appealingly blingy' meeting point of art and metalwork

Flamboyant and colourful, the best examples of cloisonné render flowers, fruits and dragons in a rainbow of multi-hued enamel on metal, enthuses Matthew Dennison.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Settlers from the Islamic world, travelling to the western Chinese province of Yunnan late in the 13th century, are most often credited with introducing to the Yuan dynasty a method of decorating metal vessels with coloured enamels. Acclaimed by Caroline Schulten, Sotheby’s European head of Chinese art, as ‘incredibly decorative, wonderfully colourful and even appealingly blingy’, this technique is known today as cloisonné.

‘It’s a very splendid, flamboyant decorative style, especially in the case of early Ming dyn-asty pieces, the colours of which are particularly vibrant,’ explains Dr Schulten, who attributes cloisonné’s perennial appeal for European and Chinese collectors to a combination of polychrome sumptuousness and an engaging repertoire of decorative motifs including flowers, fruit and dragons.

An early Ming-dynasty cloisonné enamel and gilt-bronze ewer, probably commissioned from the imperial workshops by the Yongle Emperor as a gift for a Buddhist dignitary and valued by Sotheby’s Hong Kong this summer at a figure in excess of 20 million HKD (£2 million), memorably embodied Dr Schulten’s verdict.

The entire vessel was covered with a jewel-like pot pourri of floral and foliate motifs: cartouches of stylised lotus flowers and scrolling stems on its turquoise-ground body, around the ewer’s neck camellia, peony and pomegranate blossoms in mustard yellow, rich lapis lazuli blue, red, white and a glassy Brunswick green.

Chinese views of cloisonné were once markedly less enthusiastic than Dr Schulten’s. In 1388, in his Gegu Yaolun (The Essential Criteria of Antiquities), Cao Zhao dismissed it as suitable only for a lady’s chambers. The very splendour and high-impact visual kerpow that commended cloisonné as decoration for imperial palaces and Buddhist temples, from the reign of Emperor Xuande onwards, disqualified it, in Cao Zhao’s estimate, from the more subdued, reflective environment of the scholar’s rooms.

Cloisonné is the technique of decorating metal vessels with designs of coloured glass paste or enamel. The enamel — coloured with metallic oxides — is contained within bronze or copper wires hammered or bent into a pattern across the vessel’s surface. The name derives from the French cloison or partition, referring to the metal wires or ‘fences’; in finished pieces, these gleaming outlines remain visible, different coloured enamels as clearly separated as fragments in a stained-glass window. The process was technically painstaking, involving repeated firings to address the shrinkage — and, sometimes, pitting — of the enamel at high temperatures. The vessel was then rubbed and smoothed, which polished the outlines of the cloisons, and often gilded afterwards.

During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, which spanned much of the 18th century, the imperial household closely monitored cloisonné production and the emperor decreed that the enamel wares be gilded at least three times, to ensure they accurately reflected imperial splendour. The result is a style of decoration that glows with colour, bold and confident in its design: take the gilded turquoise-ground Qing dynasty tripod censer in the collection of the Museum of East Asian Art in Bath; the British Museum’s tiny Qing dynasty gilt-mounted brush rest; or a gilded and gilt metal-decorated model stupa of the same date in the Smithsonian Institute’s collection, probably commissioned by the imperial court and intended to be filled with prayer slips.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

With its decoration of the Eight Auspicious Symbols of Buddhism, the Smithsonian’s stupa was almost certainly intended as an altar furnishing for a Buddhist temple. A number of the earliest surviving pieces of Chinese cloisonné were similarly intended for display, if not use, in temples, including incense burers and altar vases.

Dr Schulten points out the importance in Tibetan Buddhism of blue, white, red, green and yellow — the five colours of ‘rainbow light’ and the ‘rainbow body’ into which the body is transformed when enlightenment is achieved — and the prominence of these colours in early Ming cloisonné made for religious purposes.

This joyful palette, most often in bold relief against a turquoise ground, distinguished cloisonnéware from blue-and-white Chinese porcelain of the same date and enabled this imported style of decoration to find its own place within Chinese decorative techniques.

That later generations esteemed these early pieces as highly as today’s collectors is indicated by a series of cloisonné items commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor and inspired by archaic ritual bronzes, such as a flared vessel decorated with masks of mythological creatures possibly made for the Palace of Tranquil Longevity, which Sotheby’s Hong Kong sold last year for 4.495 million HKD (£450,000). More familiar to many collectors are cloisonné pieces manufactured in Japan in the second half of the 19th century, which enjoyed immense popularity as part of the fashion for Japonisme.

In the archives of the V&A Museum is a photograph by Herbert Ponting — best known for his images of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition of 1910–13 — of men working on small pieces of cloisonné in a wooden workshop in Kyoto in 1904, one of a series of photographs of Japanese artisans and craftsmen. Ponting’s photograph shows few of the stages of production, but it does indicate the complexities of the process.

Japanese cloisonné embraced a range of colours and styles of decoration, with motifs including chrysanthemum, cherry and peony blooms or rabbits similar to those found in woodblock prints. Makers such as Hayashi Kodenji evolved a distinctive style, creating finely delineated floral decoration on blue-black enamel grounds. Japanese cloisonné of this sort demonstrated considerable technical prowess.

In the West, it inspired imitators in a range of media, including ceramics and even humble tin. In 1908, for example, biscuit-maker Huntley & Palmers commissioned a ‘cloisonné’ biscuit tin of lithoprinted metal, on which a ‘Japanese’ heron flies across a turquoise ground among stylised foliage and flowers, the outlines of the details drawn in gold. More distinguished were the homegrown cloisonné vessels, produced between 1873 and 1880, by Birmingham-based metalsmith Elkington & Co. These were a genuine attempt to replicate Oriental enamelware, but production proved extremely expensive and was short-lived.

Cloisonné will never rival Chinese porcelain as an area for collecting, given the scarcity of the finest work, but its gutsy, full-throttle vibrancy delights aficionados — and, as Dr Schulten indicates, it is much, much harder to break.

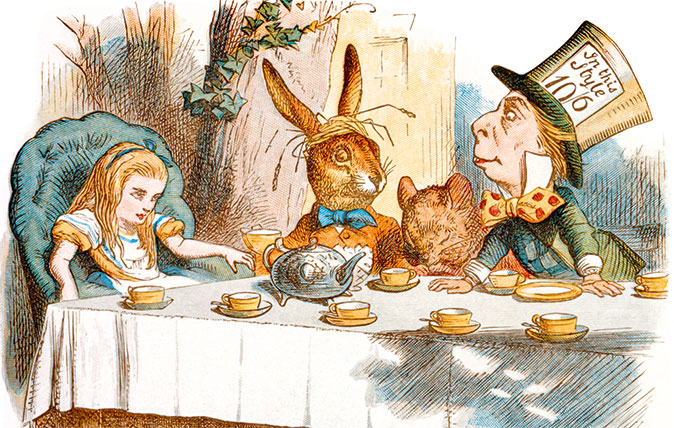

Credit: Alamy / Sir John Tenniel

10 of the greatest children's book illustrators, from EH Shepard to Quentin Blake

Matthew Dennison pays tribute to artists who painted our collective childhoods.

Credit: Getty

Port Fairy, Australia: The former whaling town with more bite than its name suggests, on Australia’s Great Ocean Road

Cruising down Australia’s Great Ocean Road, Matthew Dennison discovers a former whaling town well worth visiting.

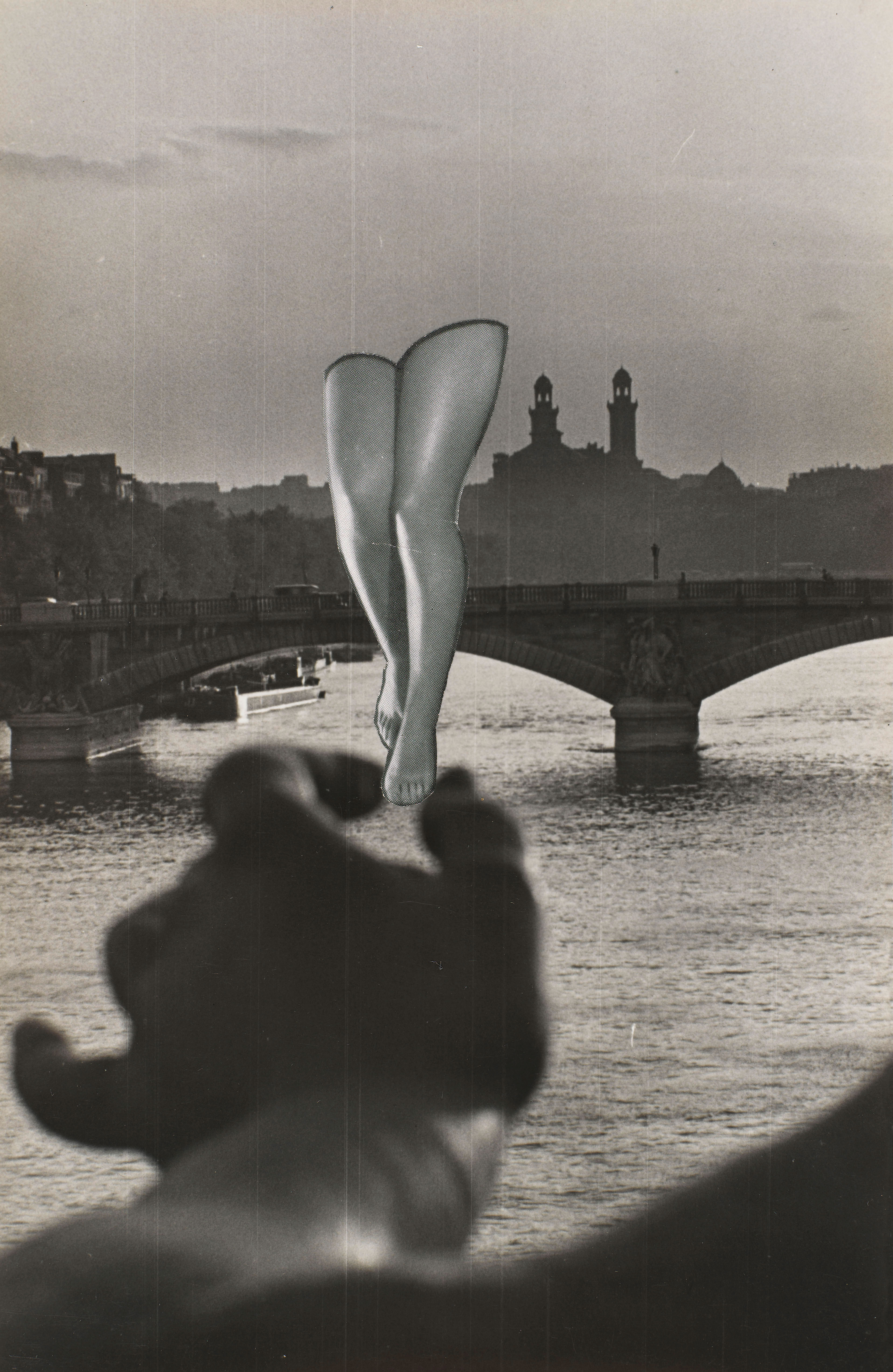

In Focus: Why Dora Maar’s vision placed her in the first rank of Surrealists

The brilliant, innovative photographer at the forefront of Surrealism was much more than merely Picasso’s mistress, says Matthew Dennison.

Credit: Joe Bailey/Country Life Picture Library

Cardigan Welsh Corgis: 'Smashing little dogs’ which deserve as much recognition as their Pembroke cousins

They’re not as well known as their Pembroke cousins that are so beloved by The Queen, but Cardigan Welsh corgis