Norman Ackroyd at Eames Fine Art Gallery, London

Norman Ackroyd is never happier than when sketching remote islands in stormy weather. Mary Miers joins him.

Norman Ackroyd is best known as the creator of sublime watercolours and etchings inspired by his sea journeys up and down the Atlantic archipelago. A visual poet in the Romantic tradition of Turner, he’s also something of a bard, weaving litanies of Norse and Celtic placenames into lyrical compositions redolent of ancient Gaelic poetry. ‘Muckle Flugga, Unst, Eshaness, Foula… Glencolmcille, Lissadell, Benbulben, Lake Isle of Innisfree… Killala, Great Bog of Erris, Inishglora, Inishkea, Achill, Blacksod Bay… Inish-bofin, Inisheer, Inishmore, Clare Head, Fastnet, Skibbereen.’ At a recent gathering of leading poets, Norman recited his oral sea chart by heart, weighing each word carefully before delivering it with just the right pitch and stress. Slow, measured and sonorous, it was a mesmerising performance and it stole the show. But then, as his former tutor, Cecil Collins, once told him: ‘You are a poet, and there are very few about. Be single-minded. Just be a poet.’

The Royal Academician credits his mother and art teacher (who slipped him the keys to the school art room) for encouraging his early talent, for, as the son of a Leeds butcher, he was expected to join the family business. Instead, he went to art college in Leeds and then became a student at the Royal College of Art.

London was where it was all happening in 1961 and Norman dabbled in Pop Art, which was all the rage. He spent some time in New York, but, then, in the 1970s, rejected the art scene to focus on his unfashionable love of landscapes.

His infatuation with the Atlantic Seaboard dates from 1974, when he went to the Orkneys and sketched the Old Man of Hoy standing sentinel against the cliffs of St John’s Head. He became fascinated with ‘the last little bits of land sticking out of the ocean’ and has since made countless journeys to the far extremities of Scotland and Ireland, braving what he calls ‘the unfettered might of the Atlantic Ocean’ to observe close at hand the remote, cliff-girt outliers teeming with seabirds and scattered with the ruins of ancient religious settlements.

‘I’m fascinated by those early Christian communities and how they lived on the edge,’ he says. ‘They were educated; they could read and write and communicated with each other not by war but through the scriptorium, boiling molluscs to extract a blue-purple pigment for ink. Latin was the internet of the period; they connected with each other across Europe and had a tremendous amount of culture; I don’t think we’d have had the great cathedrals without them.’ He continues: ‘They colonised these remote places and nearly every isle has its scholar saint, its chapels, oratories and beehive dwellings. They knew the principles of building and had a great sense of what would stand up in these desolate outposts.’

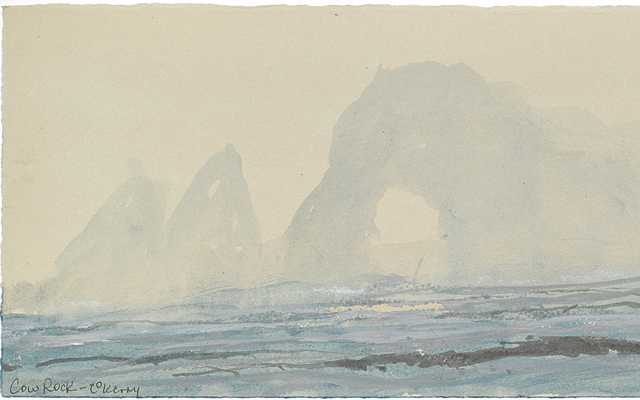

The fruit of Norman’s voyages is an astonishing body of watercolours and aquatints, a full set of which is held by the University of the Arts London, of which he is a professor. Each trip culminates in an exhibition and the publication of a box set of 10 prints. This year, he returned to Ireland to revisit some of the isles and headlands that lie within the green-armed sweep of promontories fragmenting the seaboard of Cork and Kerry between Valentia Island and Mizen Head. ‘Skellig Revisited’ opens tomorrow at the Eames Fine Art Gallery in London.

These are very much working trips, but Norman likes to relax in the evenings over good food and intelligent conversation and so he invites the same hardcore group of friends each year, sometimes augmented by the odd extra passenger such as myself. I arrived after days of mist and rain to find him in ecstatic spirits: ‘I like the sea to be a bit angry and intimidating; I find it very, very beautiful, much more interesting than a pure, pristine day. It brings the landscape into more of an abstraction which, from a picture-making point of view, is what I’m after.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

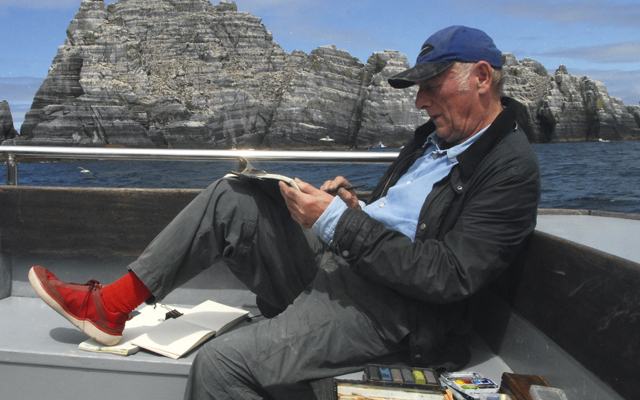

Our focus that day was the jewel of early Christianity the hermetic monastery founded by St Finnan on the rockface of Skellig Michael. As we sailed out of Derrynane Harbour, leaving Scariff Island to port and Bolus Head to starboard, the sea lightened to a slate green and the drizzle began to lift. Ahead, two jagged cones of rock floated on the horizon the Skelligs appear to be just what they are: the last unsubmerged peaks of a volcano. With nine passengers, a skipper, two crew and four dogs aboard, L’Oursan plunged through the swell towards Puffin Island, the distant Blaskets a smudge on the skyline. Norman sat at the back of the cockpit, paints laid out beside him, mixing pigment from graphite sticks, running his eyes along the line of a looming headland, daubing its purply-grey form onto paper, dipping his fingers into a bucket of water and smearing them across the sky.

He works rapidly, throwing one pad aside to dry as he grabs another, clips it open at a fresh page and begins a new sketch. These are his colour notes and records of shapes and forms, which he will work up into full watercolours back in his hotel bedroom. Cigarette in hand, he’s completely absorbed in this primeval process as the boat pitches and heaves, intermittently briefing the skipper and joining in the banter. He navigates without a map, absorbing the topography with an artist’s eye honed by years of observation, relishing the sounds of the island names rolling through his conversation.

We circumnavigate Little Skellig, marvelling at the AztecGothic architecture of sea-sculpted arches, buttresses, crenellations and chimney-like towers. Gannets throng the myriad ledges scored across the cliff face and fill the air with a cacophony of noise and motion. We land on the emerald-green face of Skellig Michael and ascend the rock-hewn stairway eyed by puffins burrowed into the sea campion.

Hunkered into the precipice, 618 steps up, the cluster of beehive cells and oratories is a perfectly preserved monument to the power of prayer in solitude. Norman captures the elemental nature of this place and something of its sanctity. ‘I want to squeeze the essence out of it and put it down in a very elegant and simple way; I’m just trying to get a resonance of humanity,’ he says.

London, where he lives and works in a former leather warehouse in Bermondsey, Norman immerses himself in the complex skill of aquatint etching, an account of which can be seen in the BBC film What Do Artists Do All Day?.

He’s a master of this highly versatile technique, producing works that can convey the drama of sea-pounded rock or raking sunlight, the softness of a band of rain or the crispness of a winter tree in a purely tonal medium, yet with the freedom and fluidity of watercolour.‘I just love the medium; I’ve never tired of it for 50 years,’ he says. ‘There’s a huge desire to make them; I let the eye look and the hand do what the eye and heart want. I don’t think about the marks I’m making, I let them happen; it’s very instinctive.’

He points out how abstract his etchings can appear, even though they’re based on geological forms. He’s not after a faithful representation, but rather an image based on something that exists.

Norman remains immersed in his sea journeys long after his return. Watercolours and other works in progress cover every surface and hang from the beams of his living room; he’s surrounded by maps and poetry books, books about lighthouses and books on Celtic history and the places that obsess him. ‘It’s very tranquil here, great for thinking. Before I go on a trip, I always get in stocks of paper and materials, cut the copper to size and have it all prepared so that everything is ready to hand.’

Now, for an intense period, he will get up to work at dawn, moving ceaselessly through three floors from the etching ‘factory’ at ground level to his living quarters above, working on several pieces simultaneously. ‘I don’t like finishing in a rush I’m always touching them up.’ His new exhibition of prints and watercolours for sale illustrates his working methods, charting the transformation from sketches into finished paintings and etchings. Also on show are maps, etching-stage proofs, watercolour studies and photographs from the trip. And, as Norman continues to work in his nearby studio, new etchings will be added to the show.

‘Norman Ackroyd: Work in Progress | Skellig Revisited’ is at Eames Fine Art Gallery, 58, Bermondsey Street, London SE1 from September 3 to Oct-ober 4 (020–7407 6561; www.eamesfineart.com) ‘St Kilda to Muckle Flugga’ is at The Fine Art Society, 6, Dundas Street, Edinburgh from October 2 to 31 (0131–557 4050; www.fasedinburgh.com)

Out of Chaos: Ben Uri: 100 Years in London

Catherine Milner is impressed by powerful works by Jewish artists.

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.