The 102-year-old, the armed robbers and the 'blazing' Picasso which helped Sotheby's sell $1 billion of art in a month

November's major auctions witnessed some truly extraordinary sales — not least thanks to the sale of the collection of Emily Fisher Landau. Huon Mallalieu takes a look.

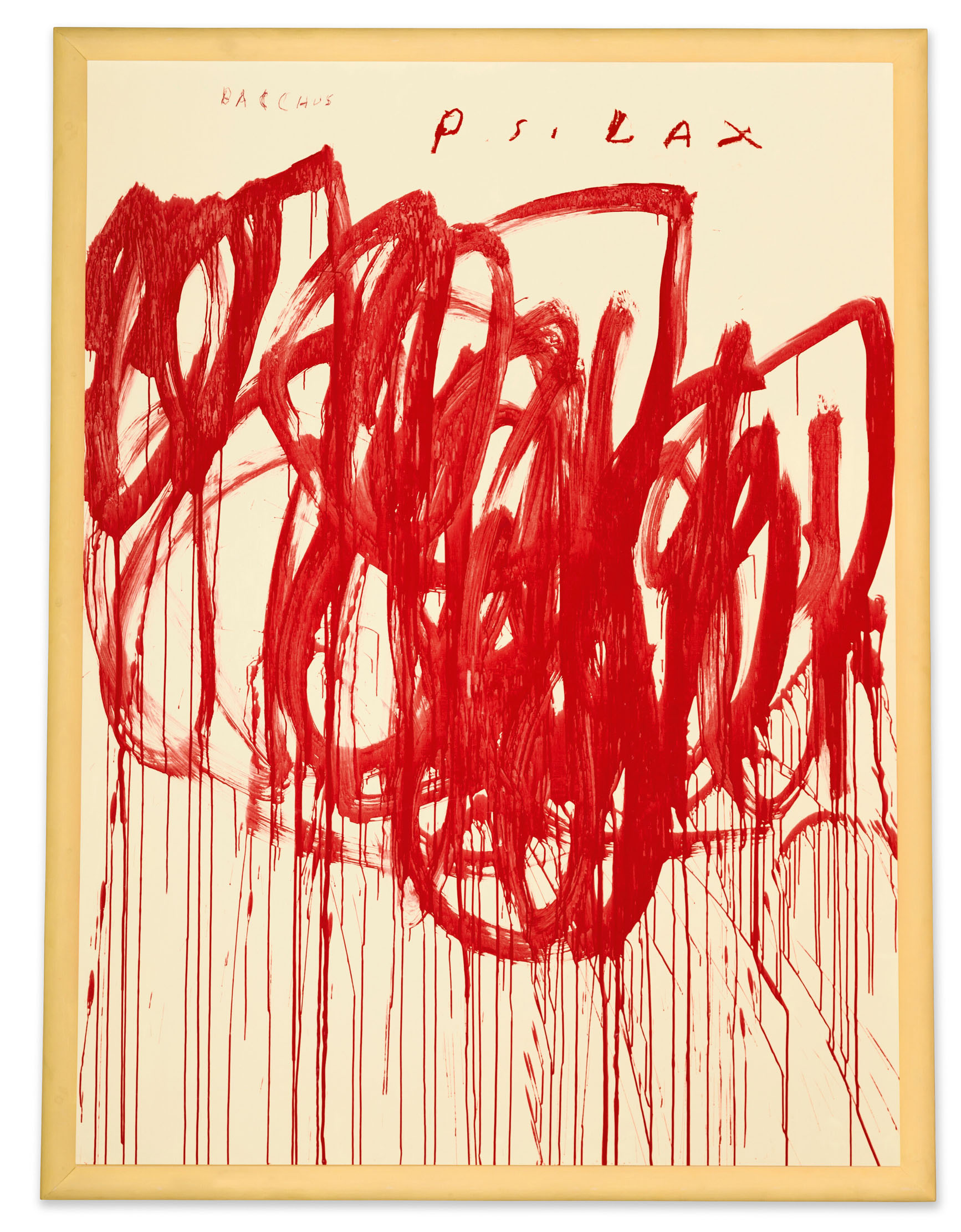

Cy Twombly (1928–2011) is an artist who does not so much divide as violently cleave opinions. For many years, I have tried to understand the loops, swirls and splashes for which he was best known and I have failed almost entirely, but many judges whose opinions are to be respected, including David Sylvester, Nicholas Cullinan and Tacita Dean, rate them highly.

Twombly liked to place himself with Poussin as an interpreter of classical mythology, but it is not always easy to see why. For the cataloguer of his typically vast, 104¾in by 79in Untitled (Bacchus 1st Version II) at Christie’s New York (Fig 1), it ‘might track the upward flight-path of spirit in rapture, or a cataclysm of debauched violence’ and the vivid crimson could, indeed, bring blood-frenzied bacchanals or the pavement afterlife of a chicken tikka masala to mind, but without the inscription — not a title, of course — would one really get it? That did not trouble the buyer, who paid a low-estimate $19.96 million (about £16.25 million) for it in Christie’s evening 21st-century sale last month.

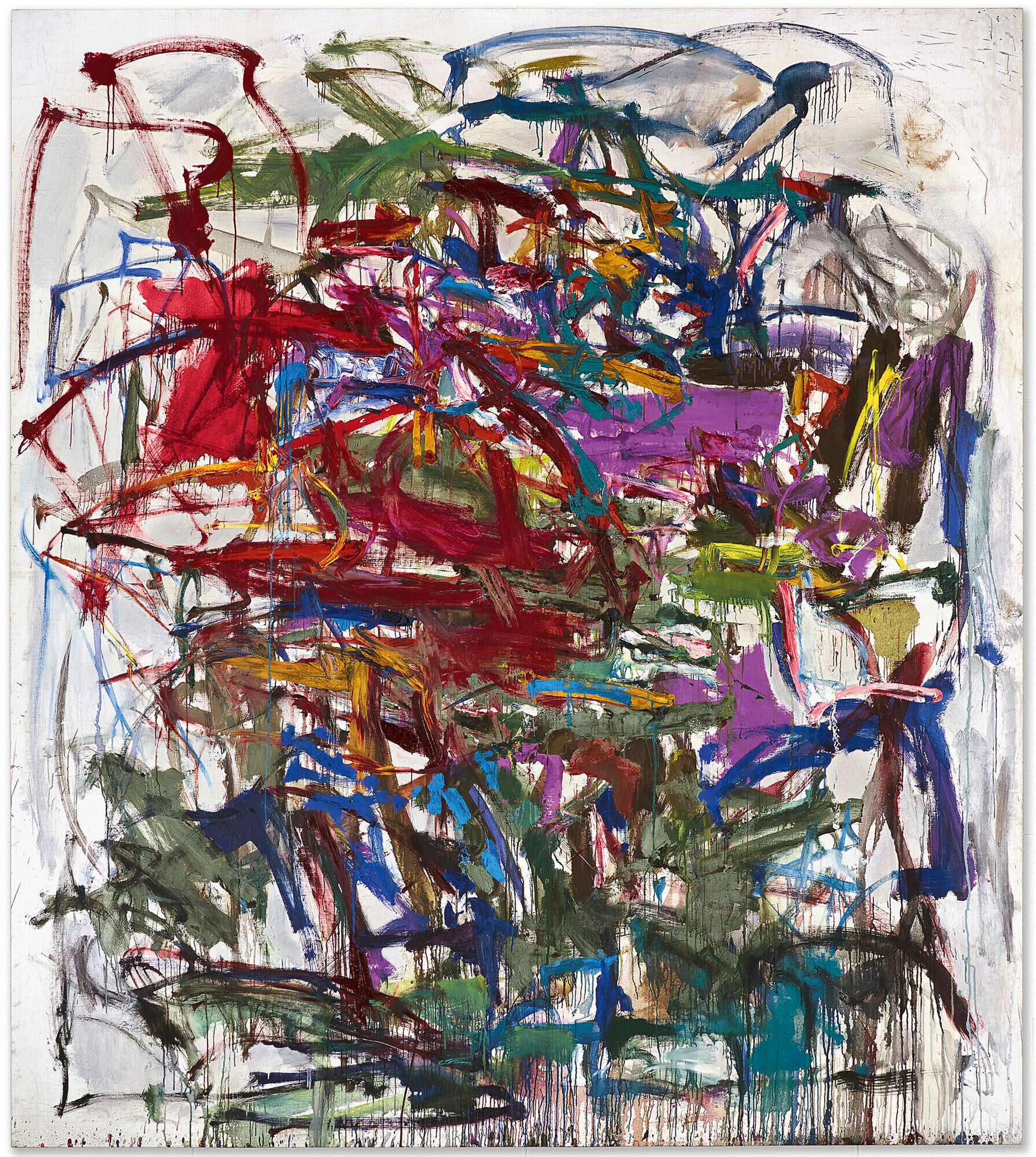

If I happened to seek a swirly work, rather than Twombly, I would have considered Joan Mitchell’s 97½in by 86½in canvas dating from about 1959, another Untitled, priced $29.16 million (about £23.7 million), also at Christie’s (Fig 4).

Mitchell said that, although she could never mirror Nature, she painted ‘from remembered landscapes that I carry with me’ and I find that much easier to see in her work than any mythology in Twombly’s.

The November week of Impressionist to contemporary sales at Sotheby’s New York made a total of more than $1 billion — to be precise, $1,099,452,061 or £893,863,464 — with Christie’s taking about $860.84 million (about £699.87 million) for its sessions. I am fairly sure that, in about 1970, when I was at Christie’s, the annual turnovers of the firms would not have touched those figures if converted to today’s equivalent money.

The biggest contribution to those totals was made by Sotheby’s 111 works from the collection of Emily Fisher Landau, who died in March aged 102. In 1969, when she was out at lunch, armed robbers disguised as air-conditioning engineers broke into her New York apartment and looted the splendid jewels given to her by her property-developer husband. She applied the insurance payout to acquiring modern art, having bought a few things earlier, notably a mobile by Alexander Calder, which she had carried home on the bus, attracting no comment. With the insurance money, however, she became not only a major collector, but a generous donor to the Whitney Museum of American Art and an important patron for younger artists. On occasion, she bought entire exhibitions. The artists and the Whitney should remember the burglars in their prayers. She also had her own charge-free museum in a former parachute-harness factory on Long Island.

The most expensive work from her collection was Picasso’s 51in by 38in Femme à la Montre of 1932 (Fig 2 - pictured at the top of the page), one of the blazing signal lights of the artist’s break-up with his wife, Olga, and lust for the youthful Marie-Thérèse Walter.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The wrist watch, it has been suggested, had symbolic meaning for Picasso, serving as a memento mori marking the progress of his affairs. In 1917, he had painted Olga wearing one, apparently then unusual for a woman; 15 years later, it was Marie-Thérèse; shortly afterwards, as that passion, too, waned, he painted a distressed figure that could have been either woman, again wearing a watch. Did Dora Maar get a watch at the end of her turn in his sun?

Fisher Landau bought that painting in 1968 from the Pace Gallery in New York, which had it from the great Swiss dealer Ernst Beyeler, who had himself bought it directly from Picasso in 1966. It would be interesting to know what the various prices were then, as, at $139,363,500 (about £113.3 million), it is now the second most expensive Picasso to have been auctioned.

There was a Calder mobile at Sotheby’s, but not the one Fisher Landau had carried on the bus, as Red Comber (Fig 3) in sheet metal, brass, wire and paint had been acquired only in 1987. It sold for more than $1.9 million (about £1.55 million).

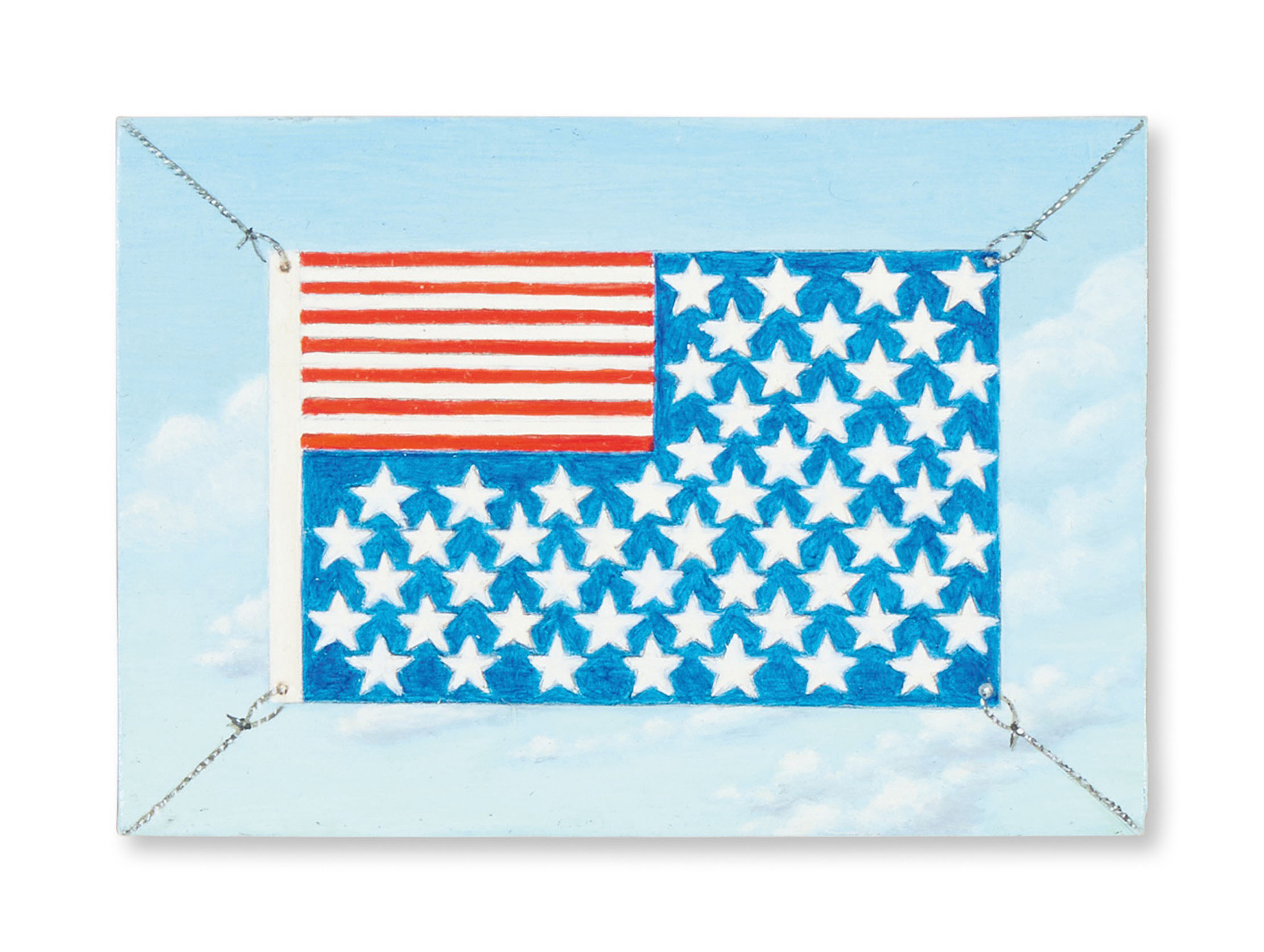

Not everything was priced in multi-millions. The cheapest and smallest — it comes as a relief after the gigantic ambition of Twombly and others — was a 2in by 2¾in panel, Collector’s Item, painted in 1990 by Fanny Brennan (Fig 5). It shows an American flag with stars and stripes reversed and it sold for an unassuming $5,334 (£4,337).

Huon’s pick of the week

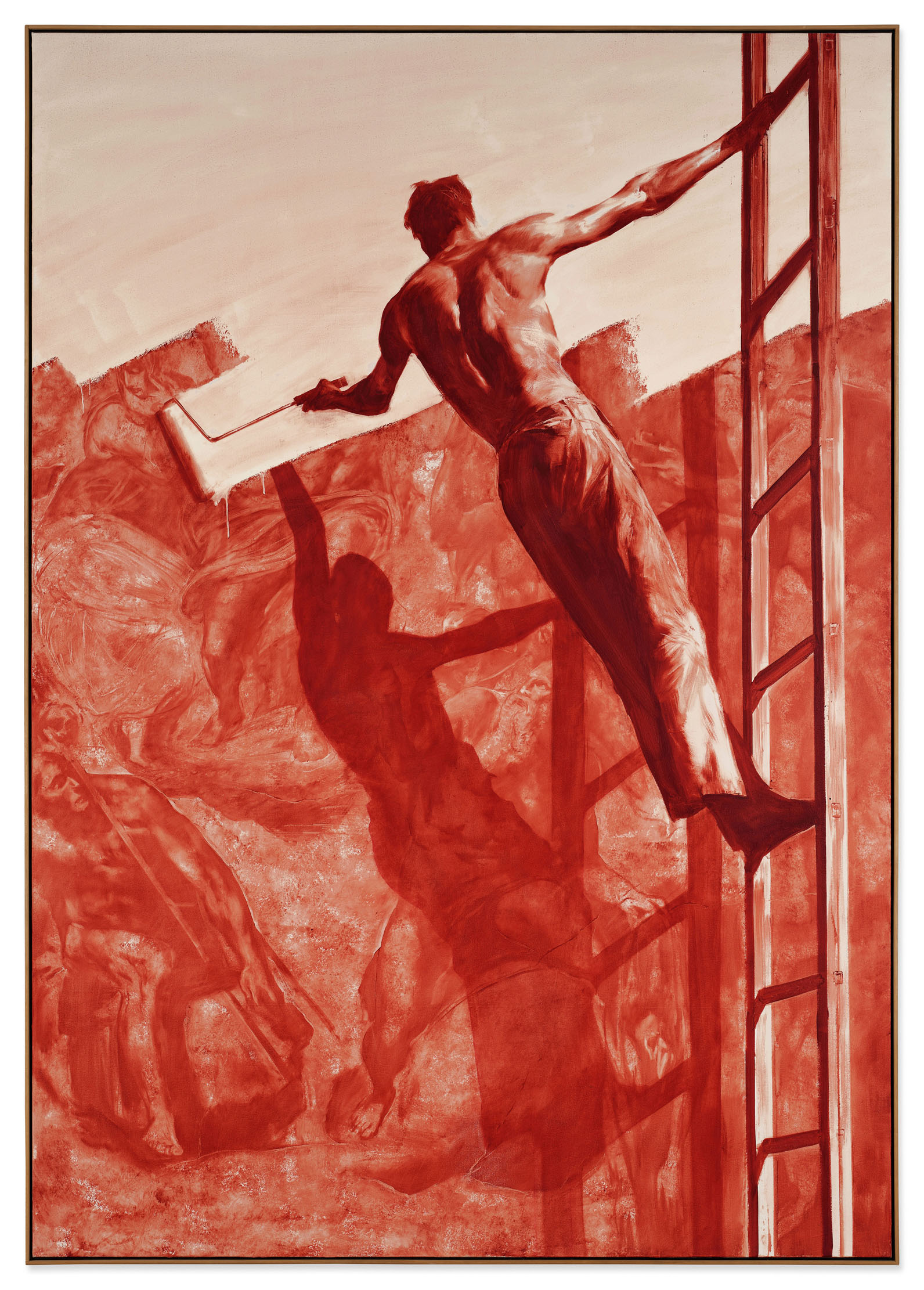

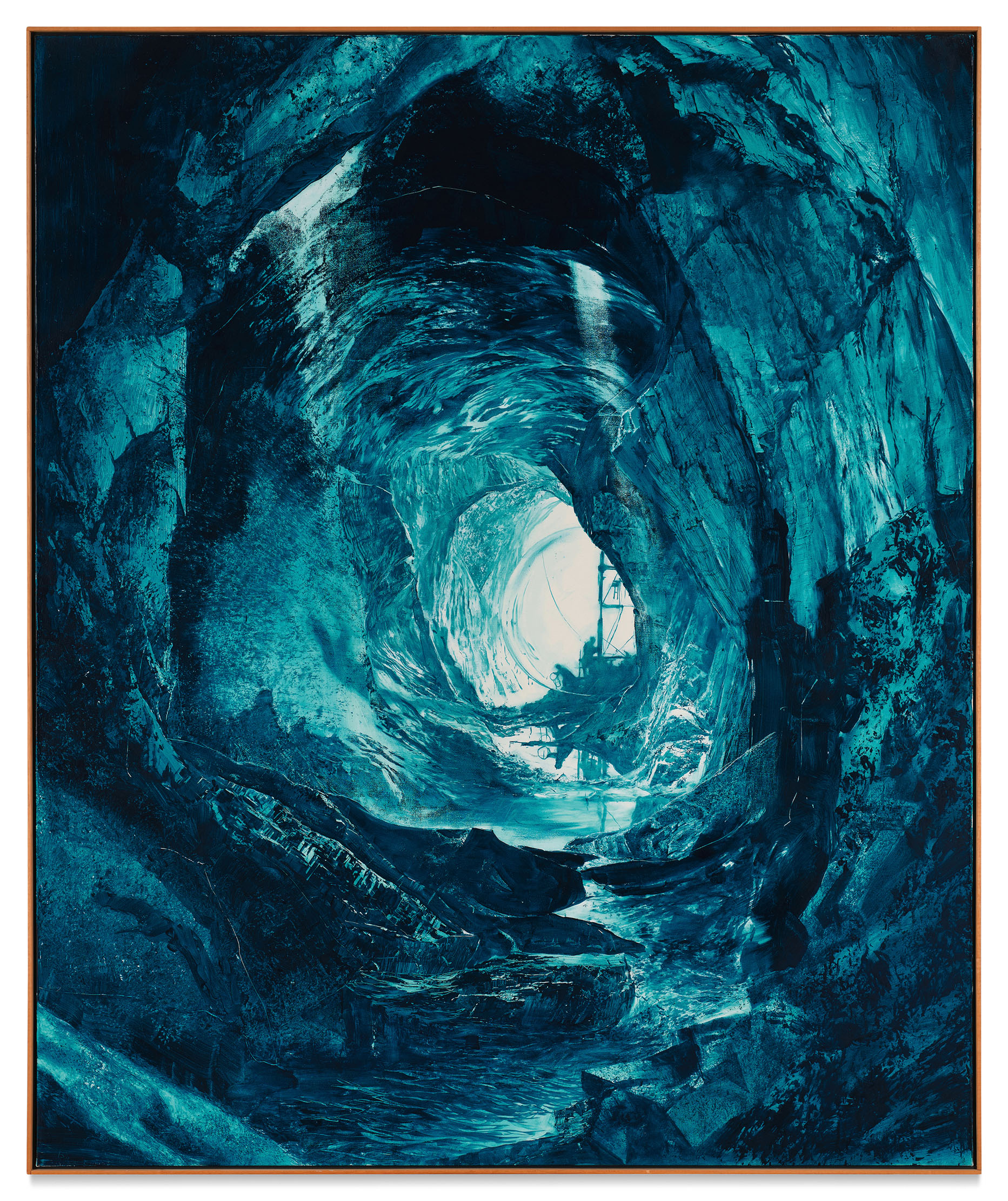

Although he deals with philosophical, literary and perhaps spiritual matters, the Californian Mark Tansey (b. 1949) has not only a sense of humour, but a sense of fun. He also works in a hyper-realistic style and his paintings are intriguing and pleasing to the eye. All of which could have made it difficult for him to scale the upper reaches of the modern art world, but he made it.

His technique is reminiscent of the way a mezzotint engraver first inks the plate and then scrapes and polishes to achieve tones and highlights. Tansey primes his canvas with white gesso, blocks out general forms of the composition by covering sections with colour and removes layers of paint to reveal varying degrees of the underlying canvas.

Emily Fisher Landau’s sale had three Tanseys, two bought in 1987 from perhaps his earliest New York exhibition and the third a decade later. The red-and-white 97in by 68in Triumph over Mastery II (above; $11.8245 million, about £9.61 million) shows a workman on |a ladder roller-painting a wall. Gradually, however, one perceives that it is not any wall, but Michelangelo’s Last Judgement. Furthermore, he is painting out his own shadow, perhaps his soul.

The 77¼in by 64¼in Installing the Lens ($4.5 million, about £3.658 million) blends Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’ with the saying ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ and the 26in by 40in Oil Sketch for Mont Sainte Victoire ($666,750; £542,073) references Cèzanne’s bathers (who change sex and are clothed in the reflection), but also, possibly, Sargent’s Gassed.

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.