The captivating art of the Japanese woodblock

Hokusai’s ferocious wave and Hiroshige’s relentless downpour stole the show at a sale of ukiyo-e prints earlier in the summer

The dramatic effect that the 1854 opening up of Japan to the world had on Western art and fashion is well known. In fact, Japanese objects had been shown in London as early as 1825, then at the Great Exhibition in 1851 (although there they were undocumented) and in Dublin in 1853.

In 1854 itself, a Japanese selling show was held at the Old Watercolour Society’s Pall Mall gallery, where the brand new V&A Museum was a buyer. However, a much greater sensation was occasioned by the London and Paris International Exhibitions of 1862 and 1867, the latter subsequently prompting the critic Philippe Burty’s coinage, ‘Japonisme’, for the frenzy.

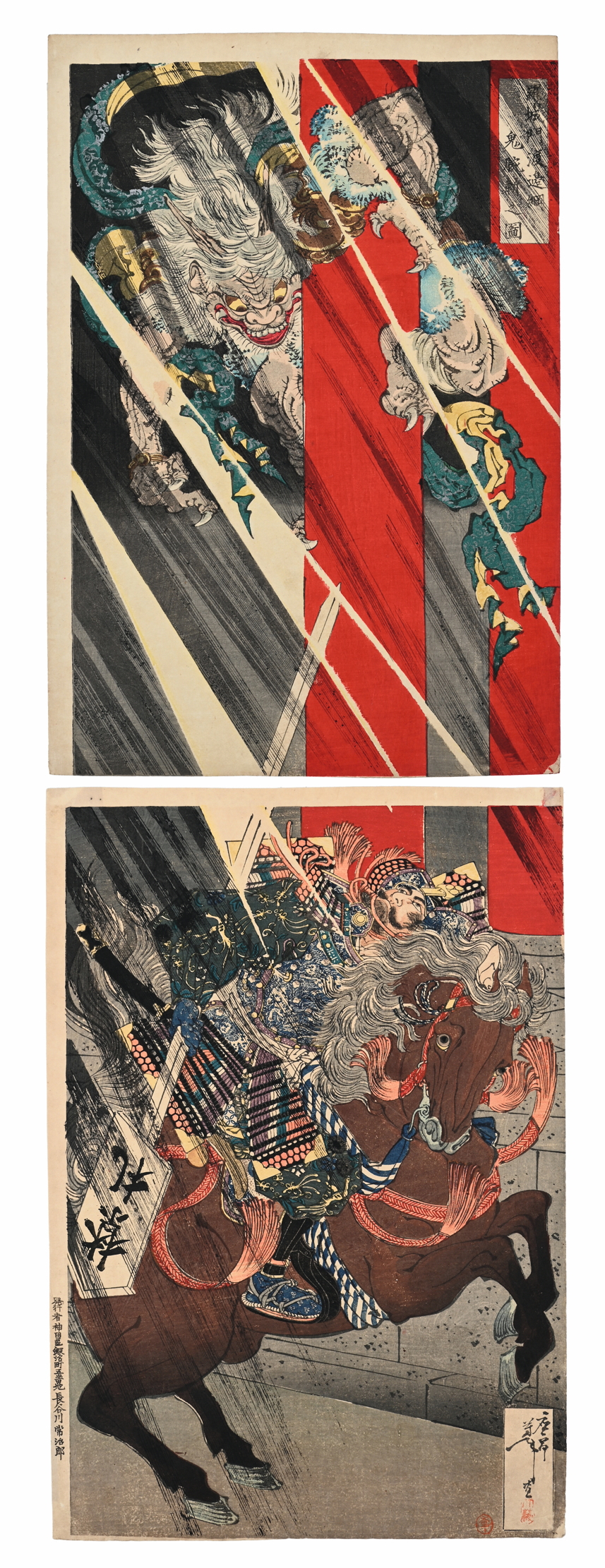

Yoshitoshi’s Watanabe no Tsuna. £2,032

The first objects to be seen were mostly contemporary, even if they did not look it to Western eyes. Lacquer, porcelain, textiles, fans, all had an immense effect and permeated the Aesthetic designs of the great Christopher Dresser, but it was ukiyo-e woodblock colour prints that had the most immediate and long-lived influence on advanced European artists, their sharp contours, planes of bright colour and innovative compositions serving as a riposte to academic norms. The Impressionists, James McNeill Whistler, Vincent van Gogh, all were avid collectors who used the prints in their work. The Japanese term translates as ‘the floating world’ and signifies the everyday world.

'The intentionally dragon-like claws of the waves seem threatening to us, but not necessarily to Japanese eyes, as dragons are protective beings associated with water'

One of the reasons that they exercised such power over Westerners is that they were not actually as unfamiliar as they seemed. Cut off as Japanese artists were, since the middle of the 18th century they had been able to study European prints brought by Dutch merchants and from them they had learned the rules of perspective, previously unknown in Japan; now, they were returning those rules in exotic guise.

By far the most widely known of all is The Great Wave by Hokusai (1760-1849). It is perspective that creates the vital contrast between the ferocity of the seas and the serenity of Fuji in the distance. The intentionally dragon-like claws of the waves seem threatening to us, but not necessarily to Japanese eyes, as dragons are protective beings associated with water.

In July, Dreweatts of Newbury in Berkshire auctioned 122 fine examples of ukiyo-e prints, for the most part, it seems, coming from private collections. Unsurprisingly, it was a Great Wave that made the top price, £378,000, more than three times the high estimate. This 9¾in by 14½in impression was one of Hokusai’s '36 Views of Mount Fuji' and dated from 1831. It came from the descendants of Thomas Sturge Moore (1870-1944), in his day a noted wood-engraver, illustrator, author and poet.

Sudden Shower by Hiroshige. £52,920

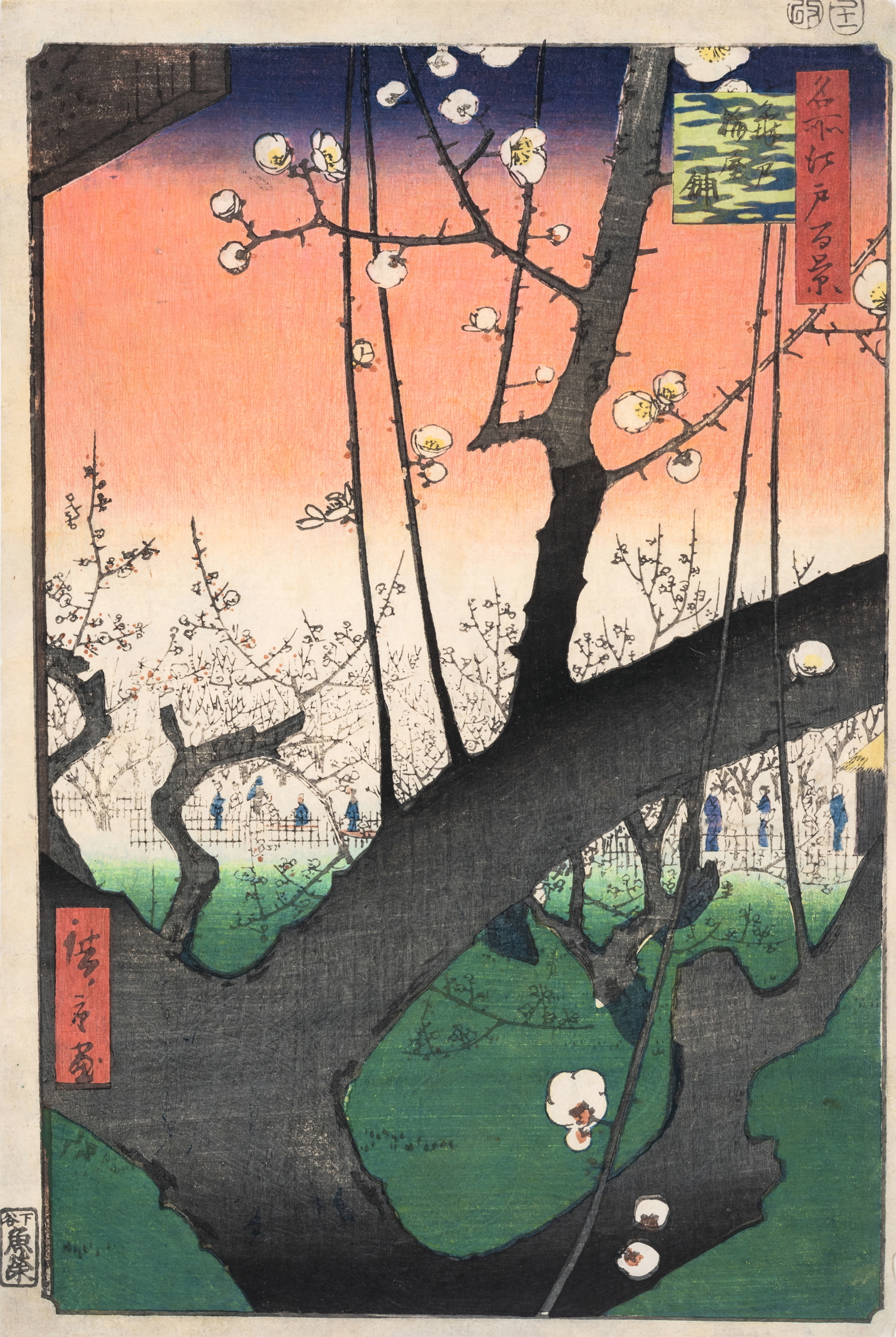

Van Gogh particularly admired Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), who in turn was influenced by Hokusai’s ‘Fuji’ series when creating his own '100 Famous Views of Edo', from the mid 19th century. In Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum are his prints from this set and some paintings he based on two of them, Plum Estate, Kameido and Sudden Shower over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake. An impression of Plum reached £13,970 in the sale and one of the Shower, generally considered the best of the set, made £52,920.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Plum Estate, Kameido by Hiroshige. £13,970

The latter’s influence on Whistler’s ‘Chelsea Bridge’ works is also obvious. Monet was another artist-collector inspired by the Japanese master’s prints and the British Museum’s current exhibition ‘Hiroshige, artist of the open road’, which continues until tomorrow, shows how his influence extends to contemporary artists, such as Julian Opie.

Hiroshige was perhaps more subtle and poetic than Hokusai and, although he came from the samurai class, his sympathy for the common people is evident. He was the last of the great ukiyo-e practitioners before Westernisation flooded over Meiji Japan, although the floating world did have an afterlife.

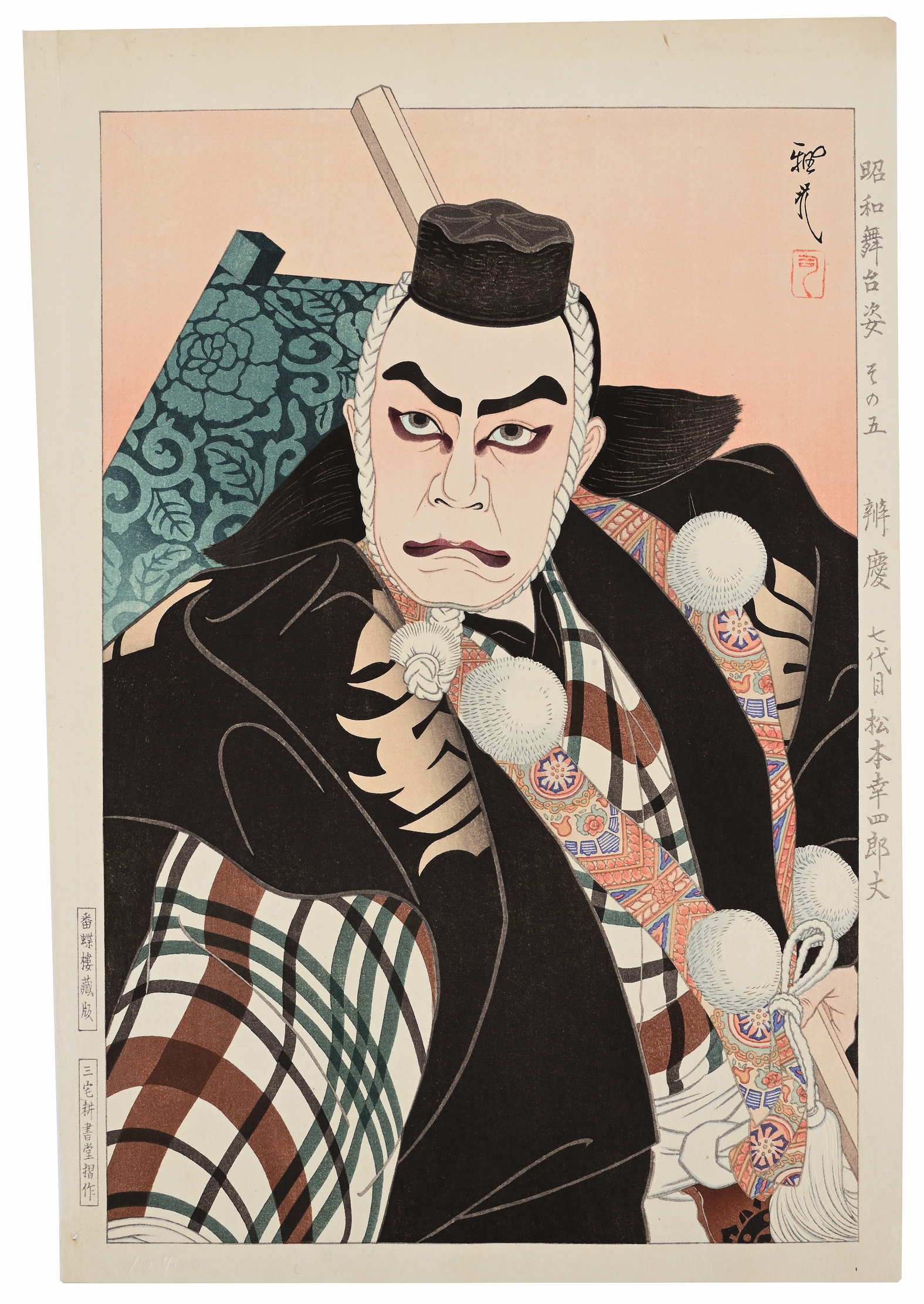

Matsumoto Koshiro VII by Masamitsu. £1,397

One aspect of ukiyo-e that proved fruitful for artists was the theatre, which also linked them to another chief source of subject matter, history, often blended with mythology. Thus, a portrait of the actor Matsumoto Koshiro VII by Ota Masamitsu (1892-1975) is not only a powerful image of a contemporary figure, but a reminder of the distant past, as he is in character as Benkei, a 12th-century monk who became a legendary warrior (£1,397).

As in Europe, if a print proved popular in Japan, later impressions might be issued from the blocks, so collectors looking for more than decoration need to inform themselves before buying. At Dreweatts, there was a two-sheet print of the hero Watanabe no Tsuna cutting off the Demon’s arm at Rashomon by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), which sold for £2,032.

I do not have the original estimate, but perhaps it might have made more had the cataloguers not realised that this was a reprint. In 2021, an impression of the first printing reached about $10,625 in New York.

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.