'Gems of enflamed transparencies, of bottomless blues, of congealed opals': Why glass was perfect for the elemental experimentalism of Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau masters such as Louis Comfort Tiffany and Émile Gallé turned the most fragile of materials into iridescent masterpieces that shimmered like seashells or glittered like Byzantine mosaics.

'Vases coloured like an autumn sky’ caught the eye of the Italian correspondent of The Architectural Record at the Paris Exposition of 1900. They were the work of American designer Louis Comfort Tiffany and the Italian reporter was not their only admirer: another critic celebrated their ‘almost supernatural light’, which he called ‘as roseate as a sunset’.

Glass vases produced by Tiffany’s French contemporary Émile Gallé were equally commended, in the Journal of Glass Studies, as ‘gems of enflamed transparencies, of bottomless blues, of congealed opals’. Iridescent, crackled and flashed, glass produced by luminaries of the Art Nouveau movement, resembling the shimmering interiors of seashells or the soft translucency of Roman unguentaria, inspired by Byzantine mosaics and medieval enamels, by shards of quartz and agate, has a glister, glamour and, in some instances, intensity of otherworldly colouring uniquely its own.

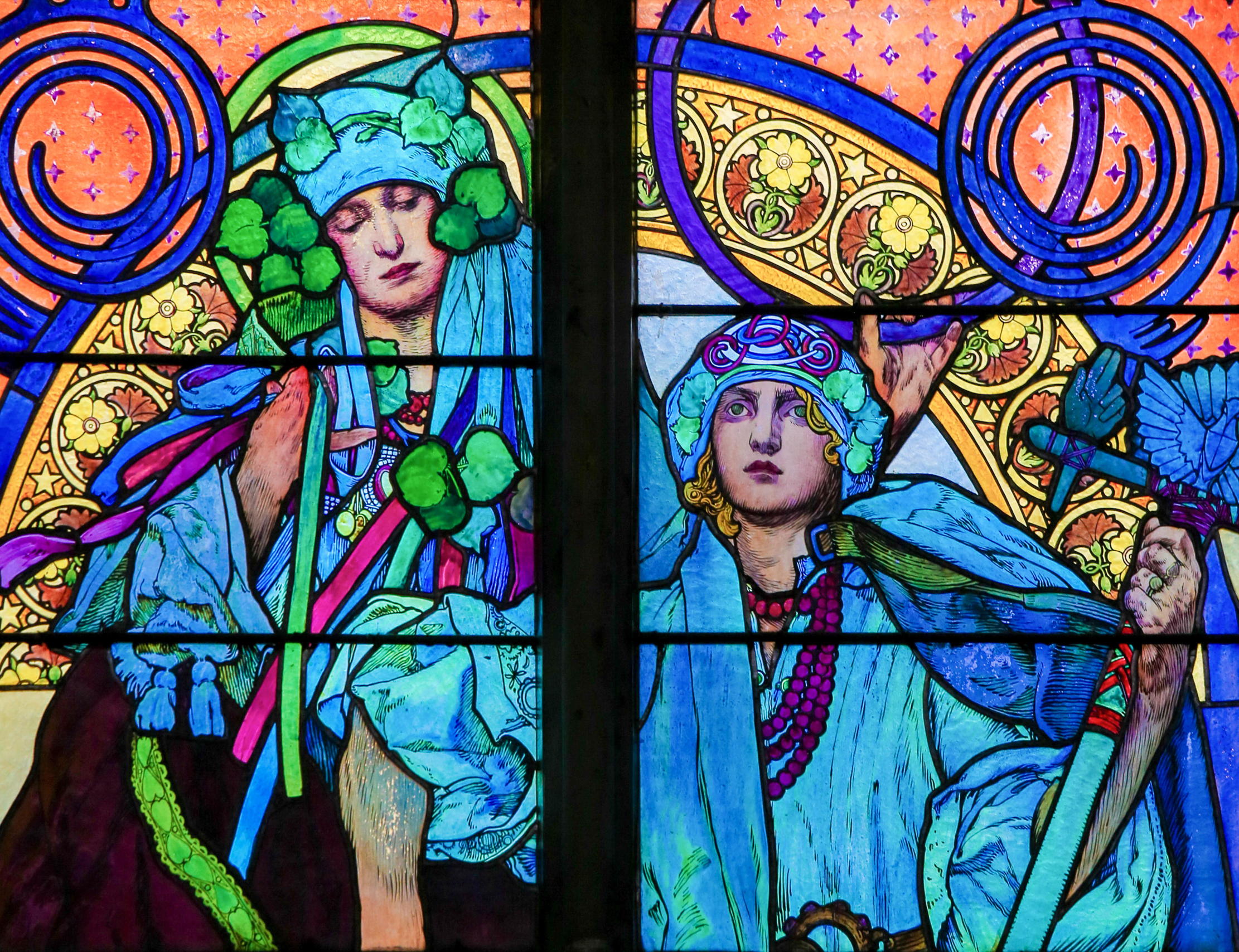

Exoticism and decadent modernity were hallmarks of the movement. The ‘new art’ style — named after the interiors emporium Maison de l’Art Nouveau, opened in 1895 at 22, rue de Provence in Paris, France, by art dealer Siegfried Bing — spread across Europe and the USA between the 1890s and the outbreak of the First World War. Characterised by exaggerated organic forms, sinuous, molten lines and asymmetry, in a rejection of the often cumbersome historicism that dominated much of the 19th century, it reshaped furniture, architecture, fabric and wallpaper patterns, metalware and — famously, through the work of Alphonse Mucha and his imitators — graphic and commercial design. Nature would determine the luscious colours, form and surface decoration of much Art Nouveau glass; it also left its imprint on the shape and pattern of everything from wrought-iron balconies to tiaras.

Abstract form: a Johann Lötz Witwe rosewater vessel.

Makers looked to plants and flowers, to swirling tendrils and falling petals, hedgerow greens and the colours of blossom, irises and rusty chrysanthemums, peacock feathers and carved cameo shells and, in the case of crystal studio founders the Daum brothers, to entire landscapes of trees. In Britain, exponents of the new style were influenced by motifs drawn from Celtic art and Japanese print-making.

So close was the relationship between the natural world and Art Nouveau that, in his native Nancy, Gallé served for many years as secretary, then vice-president of the town’s Horticultural Society and contributed a number of articles to its bulletin. ‘If Émile Gallé has renewed decorative art,’ wrote his wife, Henriette, ‘it is from having studied plants, trees and flowers both as an artist and a savant.’ The motto he adopted — ‘My roots are in the depth of the woods’ — revealed the extent of his commitment and that deep engagement shaped designs such as his Oakleaf vase of 1895.

It was no different for Tiffany. An advertisement of 1897 by Parisian shop Le Grand Depot claimed of Gallé that ‘Nature is for him the material of poetry; it has impregnated his soul’ and, two years later, the catalogue for a Tiffany glass exhibition at London’s Grafton Galleries trumpeted: ‘Never, perhaps, has any man carried to greater perfection the art of faithfully rendering Nature in her most seductive aspects.’ At the Maison de l’Art Nouveau, its entrance framed by towering sculpted sunflowers in place of columns or pilasters, Bing displayed Gallé and Tiffany glass side by side, next to paintings by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Georges Seurat, and plant- and flower-inspired jewellery made from coloured and clear glass, enamel and gemstones by René Lalique.

A stained glass window in St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague, designed by Alphonse Mucha.

As a medium, glass was ideally suited to the elegant experimentalism of Art Nouveau. ‘[It] has a molten state in which it can be blown into the most beautiful shapes,’ wrote the British designer Christopher Dresser in the early 1870s. It was the material of choice for leading masters and lesser-known designers alike, from Tiffany, Gallé, Lalique and the Daum brothers to Val St Lambert in Belgium, Beckert in Germany, Bakalowits & Söhne in Vienna, and, in Britain, Dresser himself. The latter entered into a partnership with the Glasgow-based glass-works of James Couper & Sons. Their collaboration resulted in a range of pieces that seemed to preserve in finished form the liquid flow of the medium’s molten state, achieving wonderful levels of technical proficiency.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

With its pitted and bubbled surface, Dresser’s ‘Clutha’ glass drew inspiration from ancient Roman glassware — streaked and speckled with colour, iridescent as dragonfly wings, like fragments of sea glass washed up on the shore. It was sold by Liberty in London: the shop described it as ‘decorative, quaint, original and artistic’. To modern eyes, in pieces such as Dresser’s Clutha propeller vase of about 1895, qualities of originality and artistry are more apparent than quaintness, the timelessness of the bubbled glass balanced by its remarkably modern twisted shape. The vase imitated both Nature and art. Dresser used aventurine glass, inspired by translucent aventurine quartz in which mineral inclusions create a metallic shimmer. In doing so, he also referenced the attempts of Renaissance Venetian glassmakers 400 years earlier to re-create the effects of the stone.

Christopher Dresser’s Clutha vase.

Tiffany successfully mastered something similar: in a number of decorative pieces, including some he made for himself, he reproduced the iridescence of ancient glass. He claimed that he achieved this ‘by a careful study of the natural decay of glass’, working backwards from observation. In fact, as Bing explained, the glass, when still hot, was ‘exposed to the fumes produced by different metals vaporised’, metallic oxides being the key to its iridescence.

Technical wizardry of this sort earned Art Nouveau glassmakers critical acclaim and a healthy commercial following. At its best, suggested American Arts magazine Brush and Pencil in December 1901, glass of the sort made by Tiffany was ‘opalescent as a soap bubble… heavy with jewelled effects and rich with gold dust blown into the molten glass… [and] every piece gives an almost infinite variety of beauties’. Displayed at the international exhibitions of the time, it attracted marked attention and, inevitably, spawned imitators, although, in some cases, such as the work of ceramicist-turned-glass-maker Amédée de Caranza, shimmering Art Nouveau glass did not emerge from an instinct to copy, but earlier experimentation with ceramics.

Émile Gallé’s Autumn Crocus vase, about 1900, one among many floral glass creations.

Caranza had perfected techniques of working with metallic oxides when designing faïence and began experimenting with metallic lustres on glass in 1890. He created designs for the Belgian glassmakers Val St Lambert, specialising in decorative pieces in earthy red- or tobacco coloured lustres, patterned with stylised designs of mountain ash, violets and swirling leaves. Like Tiffany, Caranza was proud of the technical prowess his pieces displayed, more than once applying for a patent for a firing method during which the metal ‘oxides are deprived of oxygen, so that they are restored to the state of native metals’.

Tiffany’s ‘favrile’ glass — the term derived from ‘fabrile’, meaning handmade — set a benchmark for lustrous shimmer and magnificent colour. Among early admirers was Max Ritter von Spaun, the owner of the Johann Lötz Witwe Glassworks in Bohemia, in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. At von Spaun’s instigation, the company embraced Art Nouveau forms, including plant-shaped vases, and the metallic iridescence of makers such as Tiffany, but ultimately achieved its own distinctive variant, ‘Phänomen’ glass, characterised by wave and stripe effects redolent of stylised seashells. Johann Lötz Witwe designs were more abstract than those produced by French and American makers, despite affinities of shape, inspiration and surface effect.

The Art Nouveau movement proved short-lived, succeeded by the geometric sleekness of Art Deco, among the leading lights of which was Lalique, who had played a key part in the emergence of Art Nouveau jewellery. Yet, for as long as fashions lasted, the movement’s designers transformed glass, moving away from the heavily cut, bright-sparkling confections of the 19th century and reinvesting this magical material with the mystique and exoticism it had possessed centuries earlier.