Exclusive: The House of Commons as you've never seen it before, 75 years on from reopening following its destruction during the Blitz

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the reopening of the House of Commons following the destruction of its predecessor in 1941 during the Blitz. John Goodall reports; photographs by Will Pryce.

On the night of May 10–11, 1941, London witnessed the last and most intense air raid of the bombing offensive known as the Blitz. A communique from the German High Command quoted in the British papers claimed that hundreds of high-explosive bombs and more than 100,000 incendiaries had been dropped on the capital. Westminster suffered particularly badly in the attack, with damage to the Abbey, Westminster Hall, the House of Lords and the Elizabeth (then St Stephen’s) Tower, although the great clock continued to operate faultlessly and Big Ben to chime.

The House of Commons, meanwhile, was hit by a high explosive bomb and then engulfed with flames caused by an incendiary. Next morning, the chamber — created by Charles Barry and Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin just over 90 years previously as part of the great Victorian rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster — was reduced to rubble and the adjacent Members’ Lobby left a roofless shell. The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, visited the next day. According to The Daily Telegraph he ‘said little during his tour’, but ‘frowned for most of the time the damage was being shown to him’.

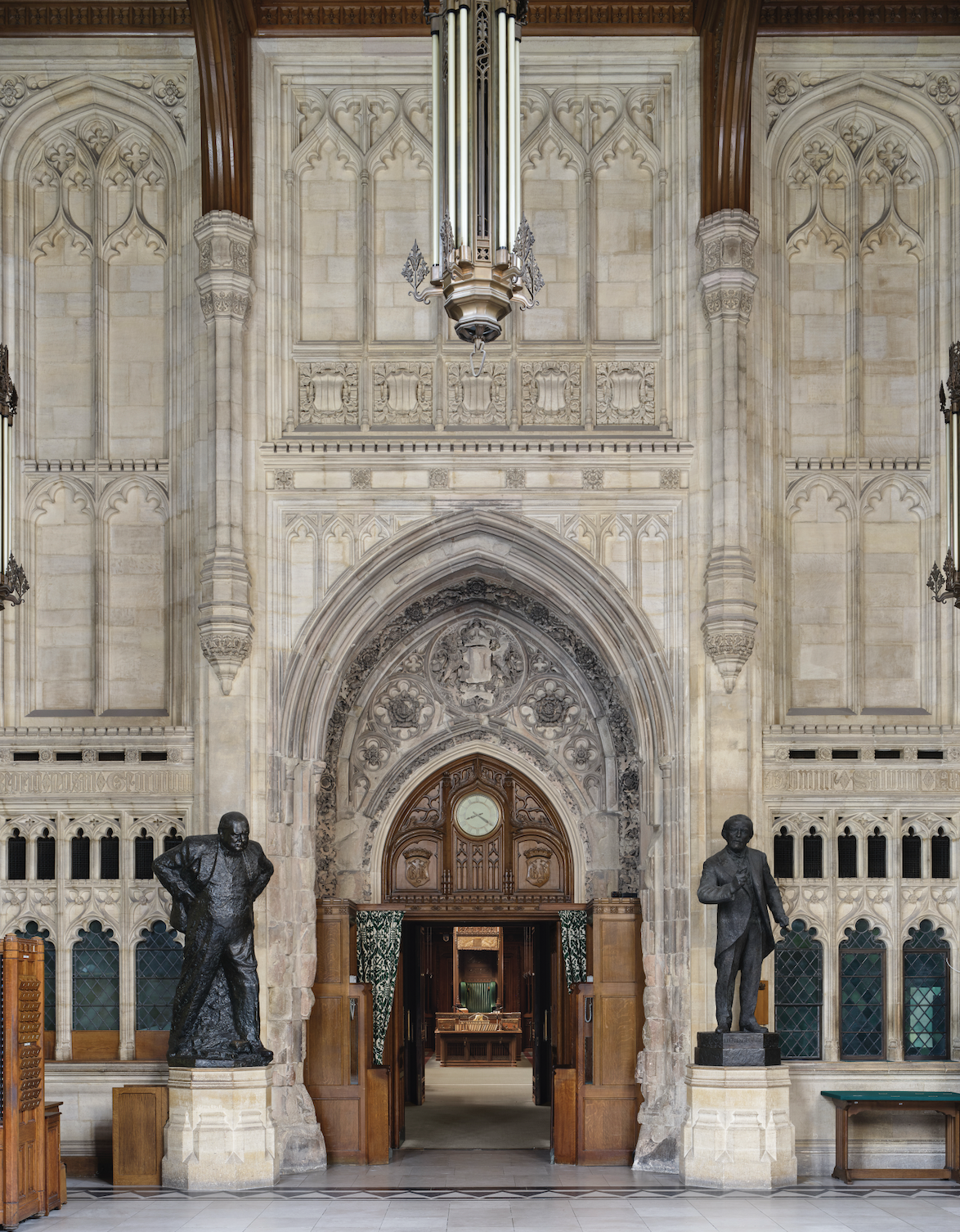

The towering interior of Central Lobby.

It was more than two years after the event, on October 28, 1943, that the Commons gathered in the borrowed chamber of the House of Lords to discuss its future accommodation. From Hansard, it’s clear that the turnout for the debate was thin, but, as war raged across Europe, the Prime Minister moved the motion in characteristically magisterial terms.

‘We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us,’ he asserted. ‘Having dwelt and served for more than 40 years in the late Chamber, and having derived fiery great pleasure and advantage therefrom, I, naturally, would like to see it restored in all essentials to its old form, convenience and dignity. I believe that will be the opinion of the great majority of its Members. I am, therefore, proposing in the name of His Majesty’s Government that we decide to rebuild the House of Commons on its old foundations, which are intact, and in principle within its old dimensions, and that we utilise so far as possible its shattered walls.’

The House of Commons' chamber was deliberately designed to not be big enough to contain all of its Members — so that Debates would not be 'conducted in the depressing atmosphere of an almost empty of half-empty chamber.'

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, Sir Winston Churchill, Clement Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, and Baroness Margaret Thatcher are all honoured with bronze statues in the Members' Lobby.

The Prime Minister went on to urge that the new building should necessarily respect two ‘characteristics’ of its ruined predecessor. First, that the new house should likewise be ‘oblong’. It was a shape, he argued, that ‘much favoured’ the two-party system and physically emphasised the momentous political nature of crossing the floor, as he could personally attest. By contrast, the ‘semi-circular assembly, which appeals to political theorists’, made it ‘easy for an individual to move through those insensible gradations from Left to Right’.

Second, the new chamber ‘should not be big enough to contain all its Members at once without over-crowding’. Otherwise, he opined, ‘nine-tenths of its Debates will be conducted in the depressing atmosphere of an almost empty or half-empty Chamber’. Added to which, ‘the essence of good House of Commons speaking is the conversational style, the facility for quick, informal interruptions and interchanges’. This required ‘a fairly small space’, which would also create ‘on great occasions a sense of crowd and urgency’.

The rebuilding, he suggested, should commence after the war, but the plans for it should be laid immediately to avoid any ‘injurious hiatus in the continuity of our Parliamentary life’ in what he predicted would be the stormy politics of post-war years. In his peroration, he thanked the Lords for ‘our sojourn on these red benches and under this gilded, ornamented, statue-bedecked roof’ — a reference to the superb interior in which he spoke — but he ended with a quotation from the sentimental song Home Sweet Home (1823): ‘Mid pleasures and palaces though we may roam,/Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home.’ He then left the chamber.

The exchange of views in the debate that followed would have been eerily familiar to Barry, who was driven to an early grave by the aggressive and contradictory demands of parliamentarians during his work to the Palace of Westminster. They also resonate today, as Parliament scandalously continues to defer the hard and increasingly urgent decisions about restoring Westminster.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

One MP urged the relocation of Parliament to a greenfield site with state-of-the-art facilities on the ‘biggest scale’, including a station, aerodrome and ‘fine car park’, another that it should be rebuilt in the Classical style and a third that it should be in keeping with the Victorian Palace. There were other opinions besides. As to the shape and size of the building, some flatly disagreed that the bombed chamber was anything to admire. Had not the Commons sat in many chambers in the past?

Other parliament buildings across the globe were cited in arguments about the future form and facilities of the building and an extravagant claim was made that French democracy had been undermined by the shape of the chamber used for debates. Cost and resources featured, too. Would bombed-out families be shocked by Parliament looking after itself? Even those who wished to see the chamber restored cited the need for improvements in acoustics, lighting and press access. Where were the telephones? Were inkpots necessary?

For all this discussion, the government motion passed unaltered and a Select Committee was appointed ‘to consider and report upon plans for the rebuilding of the House of Commons and upon such alterations as may be considered desirable while preserving all its essential features’.

Astonishingly, those features were directly derived from the chapel of St Stephen, begun in 1292. Following the Reformation, this superficially adapted interior had become the first permanent home of the House of Commons. It’s from the facing ranks of choir stalls in this building that the modern arrangement of benches in the House of Commons derives, likewise the Member’s Lobby from its antechapel and the position of the Speaker’s Chair from the high altar and Gospel lectern.

In April 1944, the Committee selected the architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott from a short-list drawn up by the Royal Institute of British Architects. He was helped in this work by his brother Adrian. It was an obvious appointment. Scott had first sprung to fame in 1903 at the age of 22 as the winner of the competition to design Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral. He had since established himself as a leading architect of his generation, with an enormous diversity of projects to his name, from the K2 telephone box of 1925 to Battersea Power Station of 1929–35, and from the University Library at Cambridge of 1931–34 to replacing Waterloo Bridge in London in 1937–42.

The Speaker's Chair, designed for the Palace by Pugin around 1849, was destroyed when the House of Commons was bombed in 1941. The present chair was given by Australia and is made of black beanwood from North Queensland.

Scott was well versed in English and European Gothic. He agreed that the new work at Westminster had to sit stylistically with the old, but was critical of the Victorian detailing, which he described as ‘lifeless and uninteresting’. In its place, he aimed to create something ‘fresher, lighter and more alive’. Whereas Barry and Pugin had adopted an eclectic style that freely combined details of many phases of English Gothic, Scott adopted a restrained Perpendicular Style modelled on Tudor buildings. He also almost completely stripped out the heraldry from the design, which was the leitmotif of the Victorian decoration throughout the Palace.

By October, Scott had drawn up his designs, presenting them with the help of an exacting model at a scale of 1:48 by Thorp Model-makers at the considerable cost of £509 14s 2d. Building work, however, waited until the end of the war. As reconstructed, the chamber sits within the earlier walls and has a pitched roof of the same volume as its predecessor. The Victorian roof had incorporated painted panels, but Scott’s roof is plain and densely timbered. It again accommodates a skylight, but one illuminated by electricity rather than the sun (there are offices above). This detail was a concession to the demand that the rebuilt interior, like the Victorian chamber, initially had no suspended lights.

The internal furnishings were largely made using kiln-dried oak from Shropshire. This created a light finish in contrast to the stain and gilt of the earlier interior. Scott used a similar finish in many other comparable projects, including the slightly later restoration of the London Guildhall. At the Commons, he fought an unsuccessful rearguard action to prevent what he regarded as the oversimplification of the panelling as a cost-saving measure. All the carving of the oak was undertaken by Green and Vardy of Islington over a period of three years.

Internal galleries for visitors had been part of the Commons since the 1690s. These were expanded at the ends of the room and the distinct spaces for men and women integrated to create a single Strangers’ Gallery. At the same time, the columns that had previously supported them were removed, opening out the floor of the chamber. This was initially planned by Scott with more upright benches furnished with a new machine-woven wool tapestry called Replin. MPs, who had enjoyed slumping on Barry’s leather-covered originals, however, demanded that the old benches be exactly re-created with upholstery in the Tudor livery of green. In concession to the poor acoustics, a miniature speaker was fixed in the back of the benches every two seats.

Great care was lavished on the Speaker’s Chair which was independently commissioned from H. H. Martyn & Co of Cheltenham in Gloucestershire. It is carved from Australian Black Bean Wood, one of many gifts of furniture and materials made by Dominion and Commonwealth territories of what was already a rapidly shrinking Empire to the rebuilding—including inkstands, ashtrays and replacement despatch boxes. The chair’s canopy was made by Watts & Co, with embroidery by the Misses Scrivener that made use of 5,000 yards of gold thread.

The Members’ Lobby, restored to its Victorian form. Some of the plinths are still empty.

Although Scott was focused on the form and decoration of the chamber, he also faced the structural challenge of inserting it within the existing layout of the Victorian building. As conceived by Barry, the two houses of Parliament were aligned in the plan, with the Speaker’s Chair of the Commons and Sovereign’s throne in Lords just intervisible down a long enfilade that crossed the towering volume of Central Lobby. Scott’s re-creation not only preserved this alignment, but its aesthetic coherence as well.

The gutted Members’ Lobby was repaired after Barry’s design, but — as was suggested in the 1943 debate — the scarred doorway to the chamber was preserved as a reminder of the wartime damage. It is flanked by sculptures of Churchill and Lloyd George, Britain’s two 20th-century wartime leaders. All the Gothic detailing was skilfully recut using stone quarried from Clipsham, Rutland, but with updated black-letter inscriptions. To either side of the Chamber itself, Scott also created Aye and No lobbies, the tellers’ desks rolling out on rails to facilitate counts.

More practical concerns included the need to create an efficient air-conditioning system. The heating system of the old house had been a favourite subject of complaint for MPs and the task of creating a more effective replacement fell to Dr Oscar Faber. This operated with the help of a periscope that allowed the operating engineer to increase or divert the flow of air according to the level of attendance and in response to divisions. Another concern was the provision of modern communications, including scores of telephone cabinets. Offices and services were squeezed into every available space above, below and to the sides of the new structure.

The new chamber was officially opened by George VI on October 26, 1950, nearly 10 years after it had been destroyed. Many critics were regretful that Scott had been compelled to work in a Gothic style. Indeed, the fact that the Festival of Britain opened the following year in the summer of 1951 underlines exactly how counter-cultural this was. The Times correspondent observed that if art was meant to please and amaze, the new chamber would ‘be pleasing to many but will astonish no one’. Regardless of such judgements, however, Scott’s neo-Gothic interior arguably articulates in architecture the creative tension between tradition and modernity that — for better or worse — remains central to our politics.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.