170 years ago, a river of excrement ran through the centre of London, spreading stench, disease and death. The engineer and architect who cleaned it up deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as Christopher Wren

The architect and engineer Joseph Bazalgette made a contribution to British life and the wellbeing of its people that cannot be overstated. Kate Green celebrates his life and legacy.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the hot summer of 1858, the dreadful stench of human effluent lying in the dry Thames riverbed overwhelmed London. A growing population — it was then the world’s largest city, with two or three million people — combined with the Victorian enthusiasm for the water closet, had revoltingly overwhelmed the existing system. And the 'system' in question wasn't much of a solution: sewage would build up in stagnant cesspools at high tide, and pour into the river at low tide. And the numbers were horrifying: 250 tonnes of faeces were emptied into the Thames every day.

The Great Stink, as it was famously known, wasn't just a matter of the pervasive smell. A few years beforehand, in 1848, 1,500 Lambeth residents had died of cholera because they had no other option than to take water from the Thames. The great men of the age wrote about the ongoing horror, with Michael Faraday describing The Thames as 'an opaque pale brown fluid' with 'the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface, even in water of this kind.' Dickens criticised it regularly, both in articles and books, writing in Little Dorrit: 'Through the heart of the town a deadly sewer ebbed and flowed'.

By 1858, as more lay dying and with the smell reaching the nostrils of MPs in Westminster, the authorities recognised that something had to be done.

'The silent highwayman', an 1858 cartoon from Punch depicting Death rowing on the River Thames, claiming the lives of victims who have not paid to have the river cleaned up, during the Great Stink.

The man called in was in Joseph Bazalgette (1819–91), chief engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works. His epic creation of more than 1,000 miles of connected sewers, still in use today, would carry the effluent further away from the city. These new sewers were concealed in embankments — the Victoria, Albert, Chelsea and so on — built on land regained from the river that also acted as flood defences. This was controversial at the time for the displacement of so many people and businesses; for centuries before this, London life had run right down to the water's edge.

A row of houses on the south bank of the Thames at Lambeth, London, circa 1850.

In 1865, the Prince of Wales opened Crossness Pumping Station, SE2, now Grade I listed; Pevsner described it as ‘a masterpiece of engineering’ and ‘a Victorian cathedral of ironwork’.

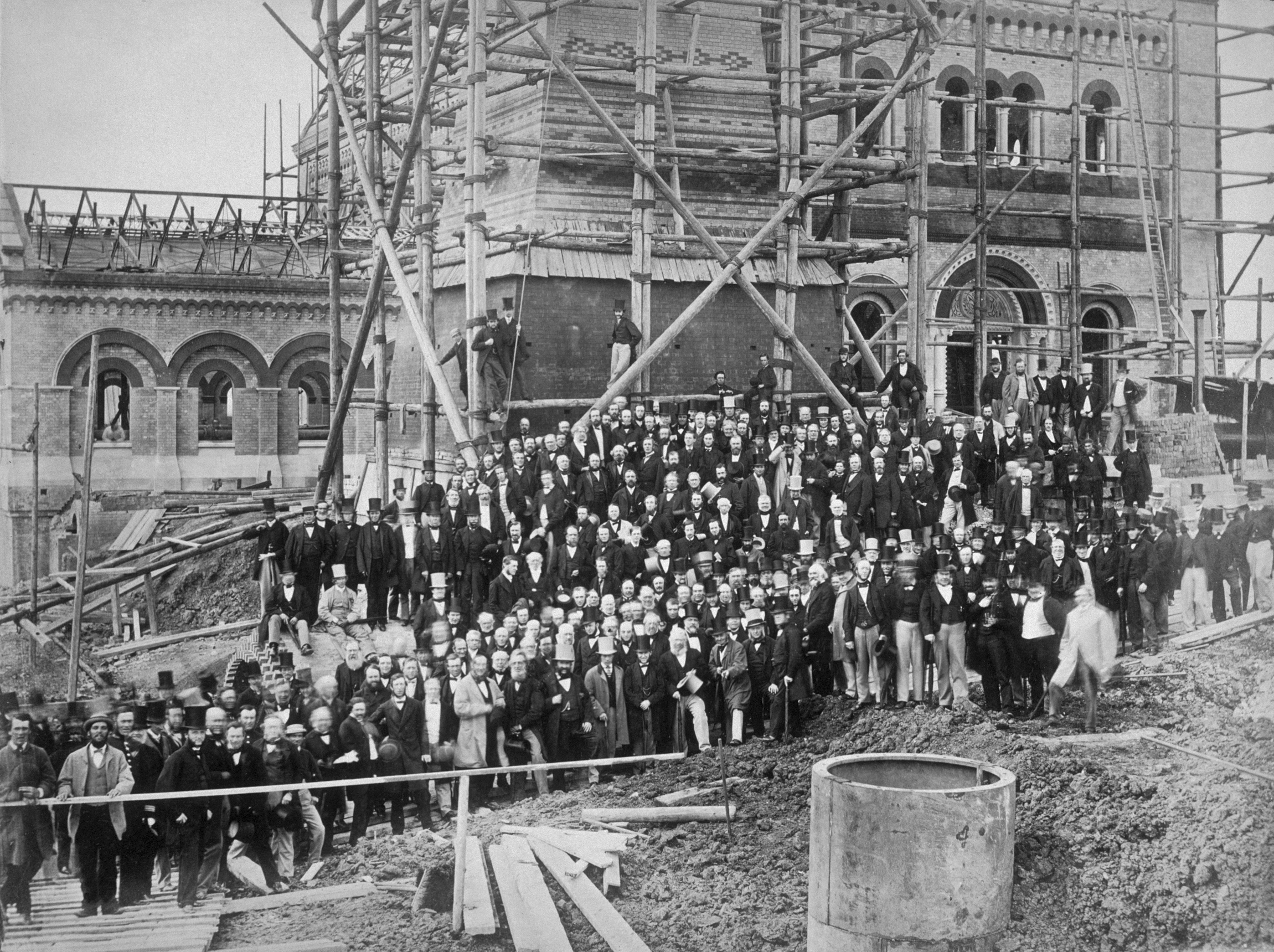

The Crossness Pumping Station under construction in 1862.

Other works have been less respectfully dubbed ‘cathedrals of sewage’, but it is no exaggeration to claim that Bazalgette transformed London with a scheme that now seems absurdly cheap (£4.2 million). Eventually, of course, it came under strain — in 2024 year, the 15-mile Thames Tideway ‘supersewer’ tunnel, an eight-year-project involving a 20,000-strong workforce, was completed.

Bazalgette, who suffered a nervous breakdown in earlier life, was clearly a workaholic. As well as the sewers of London, he redesigned Putney, Hammersmith and Battersea bridges, and on his recommendation the Metropolitan Board of Works bought 12 bridges, including Vauxhall, Wandsworth, Waterloo and Charing Cross, for some £1.5 million, freeing them from the tolls imposed by their owners. He also constructed many new roads, including Southwark Street, Queen Victoria Street, Northumberland Avenue, Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In his retirement, which only lasted two years, he enjoyed riding, keeping cows and making ‘a little hay’.

Joseph Bazalgette photographed in 1887, and as he appeared in the Fancy Portraits series published in Punch in 1883.

He has not been forgotten, though neither has he received the recognition that perhaps should be his due; this is a man who the historian and biographer Peter Ackroyd believes should be considered alongside Christopher Wren and John Nash In 2025 the National Lottery Fund awarded a £249,000 grant to restore the mausoleum at St Mary’s, Wimbledon, SW19, where the saviour of London’s health is buried.

Kate is the author of 10 books and has worked as an equestrian reporter at four Olympic Games. She has returned to the area of her birth, west Somerset, to be near her favourite place, Exmoor. She lives with her Jack Russell terrier Checkers.