Country-house treasures: A papal seal of approval at Combermere Abbey

Country houses up and down the land are renowned for their great treasures. Here we take a look at some less-well known items in their collection that hold a deeper meaning to their owners.

Country houses are famously more than the sum of their individual parts. The greatest not only unite landscape, architecture and art to symphonic effect — each element setting off the others to advantage — but reveal in countless ways the changing personalities, circumstances and fashions that have shaped them. Each house has its own story to tell and every story rightly told has details to fascinate and amaze.

Therefore, although it remains important to cherish these buildings as physical manifestations of history, as well as for the quality of their architecture and contents, it is also possible to enjoy them for the insights they offer into the personal experience of those who have lived, loved and worked in them through time. It is to explore this theme of the human interest of such homes that Country Life launches a new series this week titled Country-house treasures.

We have asked the present owners and custodians of houses great and small, ancient and modern, to choose an object from their home for which they have a particular affection and to explain the significance it has to them and the history of the building. These individuals necessarily have an unrivalled understanding of the buildings and collections they care for, so are both well placed to choose and to explain their choice. Added to which, they are presently making their own contribution to what will become the story of their homes.

'In the bonds that link the three together is the very essence of what keeps the British country house — in the face of so many challenges — loved, living and vigorous in the 21st century'

In making their selection, the only guiding principle has been to steer away from things of intrinsic value, such as Old Master paintings or fine pieces of furniture. Such objects tend to advocate themselves to a wide audience and command respect because of their perceived value. Rather, we have asked the owners to think of something that has an engaging story attached. These are the things — we suggested — that are pointed out to enliven a tour or which naturally catch the attention of visitors as curiosities. Alternatively, they might be commonplace objects that it would be easy to look straight through, but which benefit from having their presence and significance explained.

The choice has not necessarily been easy, but the results are invariably fascinating, varied and unexpected. In each case, the person who has made it has been photographed with the object in the house, sometimes in company with their spouse. We are grateful for their enthusiasm and time contributing to this series. The result on the page is a short explanatory text with a happy trinity of commanding images: caretaker, curiosity and house. In the bonds that link the three together is the very essence of what keeps the British country house — in the face of so many challenges — loved, living and vigorous in the 21st century.

By order of Pope Honorius III

Sarah Callander Beckett holds a framed papal seal or bulla issued by Pope Honorius III (reigned 1216–27), discovered at Combermere this year by a local metal-detector group. Such seals — which continue in use — have bestowed the name of ‘papal bulls’ on the documents they authenticate. By long tradition, bullas are made of lead and decorated with Saints Paul and Peter on one side (identified by the inscription SPASPE) and the name of the issuing pope on the other.

The discovery is a reminder of the medieval origins of Combermere as an abbey of the Sauvignac — and later Cistercian — order that was dissolved in 1538. It is not known to what lost document this bulla was attached.

The Roman-born Honorius III was a towering figure in European affairs, driving forward the reforms of the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215. Through his legate, Guala Bicchieri, he also played a crucial role in the English civil war that followed King John’s rejection of Magna Carta. Papal support secured the succession of John’s nine-year-old son, Henry III, to the throne in 1216. Another bulla, issued by Innocent IV (reigned 1243–54) was also discovered at Combermere in the 1990s.

Indian Summer

Richard and Susanna Bott stand on the verandah that overlooks their much-loved gardens and lake at Benington Lordship. This was one of the pioneering properties involved in the first opening of the National Garden Scheme in 1927. ‘The verandah is a favourite feature of the house,’ explains Richard, ‘popular with the whole family, including the animals. It is very much part of the history and varied character of our home and is particularly enjoyable on a sun-drenched day in high summer.’

The verandah was built in 1906 as part of the Edwardian enlargement and reorganisation of the house overseen by the architect Edward Arden Minty of London and Petersfield, Hampshire, for a former Indian railway engineer, Arthur F. Bott. Its Tuscan columns and the arrangement of rooms opening onto it — originally a drawing room, billiard room and smoking room — are reminiscent of a colonial bungalow.

Bott purchased Benington Lordship with his wife, Lilian, on retirement in 1905. At that time, it comprised a brick house of about 1700 erected over the foundations of a medieval castle. These remains inspired one owner in the 1830s to create the memorable neo-Norman gateway entrance to the house.

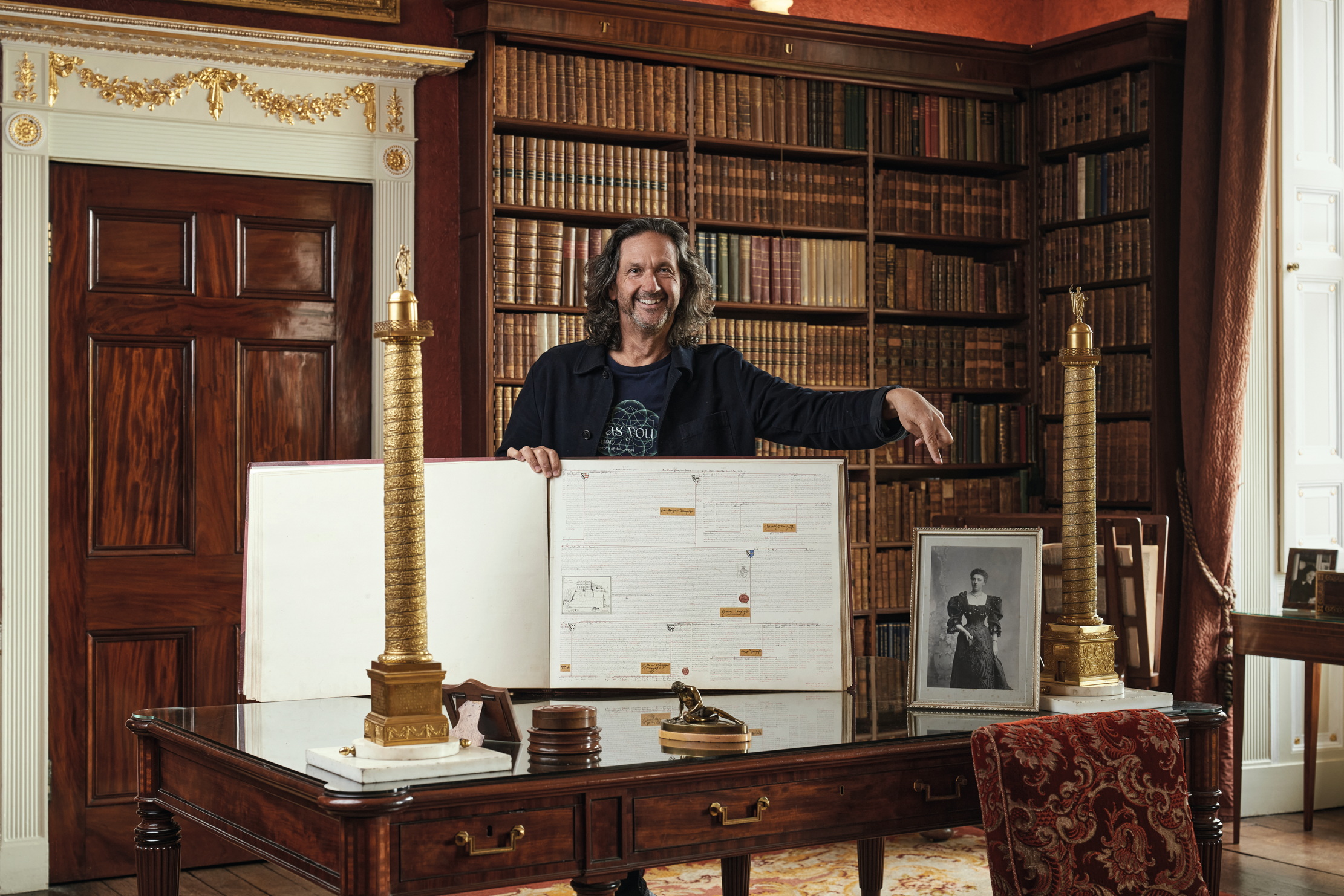

Past participants: The centuries-old documents at Broughton Hall

A close-up of the vellum document at Broughton Hall, owned by Roger Tempest

Roger Tempest holds open a densely written genealogy that traces the history of his family, owners of Broughton since the Middle Ages, back through 32 generations to 1097. ‘The continuity is astonishing and improbable,’ he muses. ‘How have we survived?’

This remarkable volume was compiled in 1889 by his great-grandmother Eleanor Blanche Tempest, whose silver-framed photograph stands on the desk. The text is written in a small, but immaculate hand on vellum with names picked out and is variously illustrated with hand-drawn illustrations, including coats of arms, seals and facsimiles of signatures. Another copy of the manuscript was presented to the British Library, where it remains.

‘This document is a window into the past,’ he continues. ‘It reveals what my ancestors lived through and how adaptable and forward thinking they were. It’s a reminder, too, I suppose, that actions are the measures of every individual. I like to think that there is a lot of courage, duty and integrity to be found here, as well as good custodianship of the land and its community.’

A life remembered: The Cobbold family's picture of portrait of Emily Bulwer Lytton

The framed portrait of Emily Bulwer Lytton, owned by Henry Lytton Cobbold.

Henry Lytton Cobbold, 3rd Baron Cobbold, holds a portrait of Emily Bulwer Lytton (1828–48). A concealed inscription declares in French: ‘When I am gone, think of me!’ Emily was the daughter of the celebrity Victorian novelist Edward Bulwer Lytton and the forceful beauty Rosina, née Wheeler.

After their acrimonious separation in 1836, Rosina tried to exact vengeance on her husband for his infidelities by writing novels based on her experiences. By the terms of their settlement, she was denied access to her children.

Henry Lytton Cobbold holds the framed portrait of Emily Bulwer Lytton. Almost forgotten, her inscription to 'remember me when I am not there' clearly resonates with the 3rd Baron Cobbold.

Emily suffered from curvature of the spine and died aged 19, alone in a boarding house in London. The discovery of her coffin in the family mausoleum — prised opened by thieves — and a box of her letters at Knebworth prompted Lord Cobbold to research and write up her tragic life in a two-volume biography.

It was asserted that she died of typhus, but she may have taken her own life, overdosing with laudanum she had been prescribed for toothache. The message on the portrait seems to have been aimed at her grandmother, in whose former bedroom it hangs.

A musical façade: The organ at Glyndebourne House

Gus Christie sits in front of the organ in the hall that physically links the house and opera at Glyndebourne. This instrument — and the purpose-built Tudor-style room that contains it — were built after the First World War by the founder of the opera, John Christie, for his composer and friend Dr Charles Harford Lloyd, the Precentor of Eton, as an inducement to retire in East Sussex. Sadly, however, Harford Lloyd died in October 1919, before the organ was completed.

The instrument was so powerful that, when it was first played, pieces of plaster fell from the ceiling. Christie went on to buy the Norfolk-based company that built it, Hill, Norman & Beard. Alterations to the neighbouring opera house in the 1950s have left the instrument as a silent monument to his enthusiasm for music.

‘Operagoers love passing through this room and all our performances are relayed here,’ Mr Christie explains. ‘This instrument is like a musical façade that introduces both the history of the house and its musical life. If we can raise the funds, I hope that one day it will play again.’

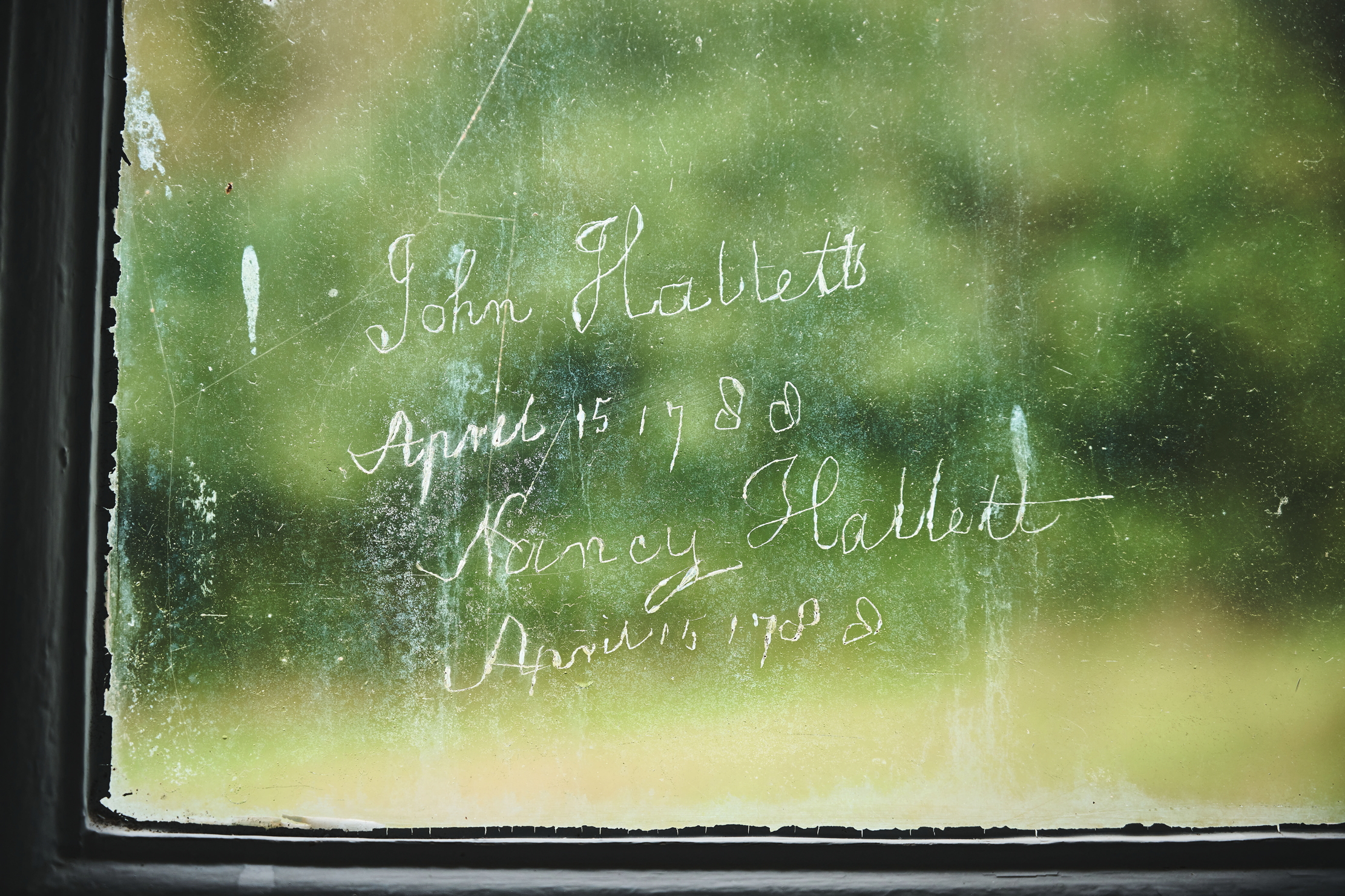

Signatures from the past — Stedcombe House, Devon

Graffiti incised in the window panes of this fine 1690s house, which Paul Zisman has been restoring with his wife, Sybella. The graffiti includes the repeated signature of John Hothersall Hallett and the date April 15, 1788.

At the time he scratched his name, John would have been 12 years old. He had eight siblings, one of whom was Nancy Hallett, who also signed her name.

Hallett inherited Stedcombe in 1814, by which time he had already built his long-term home nearby, called Haven-cliff. This was a Gothic villa overlooking the mouth of the River Axe, which he attempted to develop, cutting a channel through the beach to make — in the words of a local press report — a ‘commodious harbour… capable of admitting vessels of 150 tons burden’. He secured an Act of Parliament in 1830 ‘for maintaining and governing the harbour of Axmouth’. It lists the duty to be paid on such commodities as coal, eggs, nails, gunpowder and cattle, associated with Hallett’s diverse business ventures.

The harbour was hit hard by the arrival of the railway in the 1860s and the family’s fortunes declined with it. The estate was auctioned by order of the Chancery Division in 1890.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.