Belmont House: The 'jewel in Kent’s celebrated crown', created by a decorated soldier who was sent to prison and premature death by false accusations

Belmont House in Kent is a Georgian creation rich in military associations, now run by a trust. Steven Brindle looks at its history and the remarkable architect responsible for its design; photographs by Will Pryce for Country Life.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Belmont is a Georgian creation. Its name, relating to its elevated position and extensive views, was coined by the first builder of a house on the site, Edward Wilks, the storekeeper at the Royal Powder Mills in Faversham, Kent. Successive owners thereafter, including five generations of the Harris family, were soldiers and colonial administrators, so its history is bound up with that of Britain as a military and Imperial power. Outwardly, however, the character of the house — which was built in its present form by Samuel Wyatt (1737–1807) — belies this martial connection, for it is gentle, bucolic and domestic, with not a battlement in sight. It is two storeys high and a soft yellow colour, with broad, relaxed proportions, exuding the elegant, precise modernity of the 1790s. There is no domineering portico or giant order of pilasters (Fig 1).

Wyatt was the third son of a Staffordshire master-builder and has been overshadowed by his flashy and brilliant younger brother, James. Whereas the family sent James to Rome for an artistic education, Samuel acquired technical skills as a carpenter and builder. He learnt about construction as clerk of works at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire, and, in 1774, he moved to London, where for 30 years he ran a highly successful business as a builder and designer.

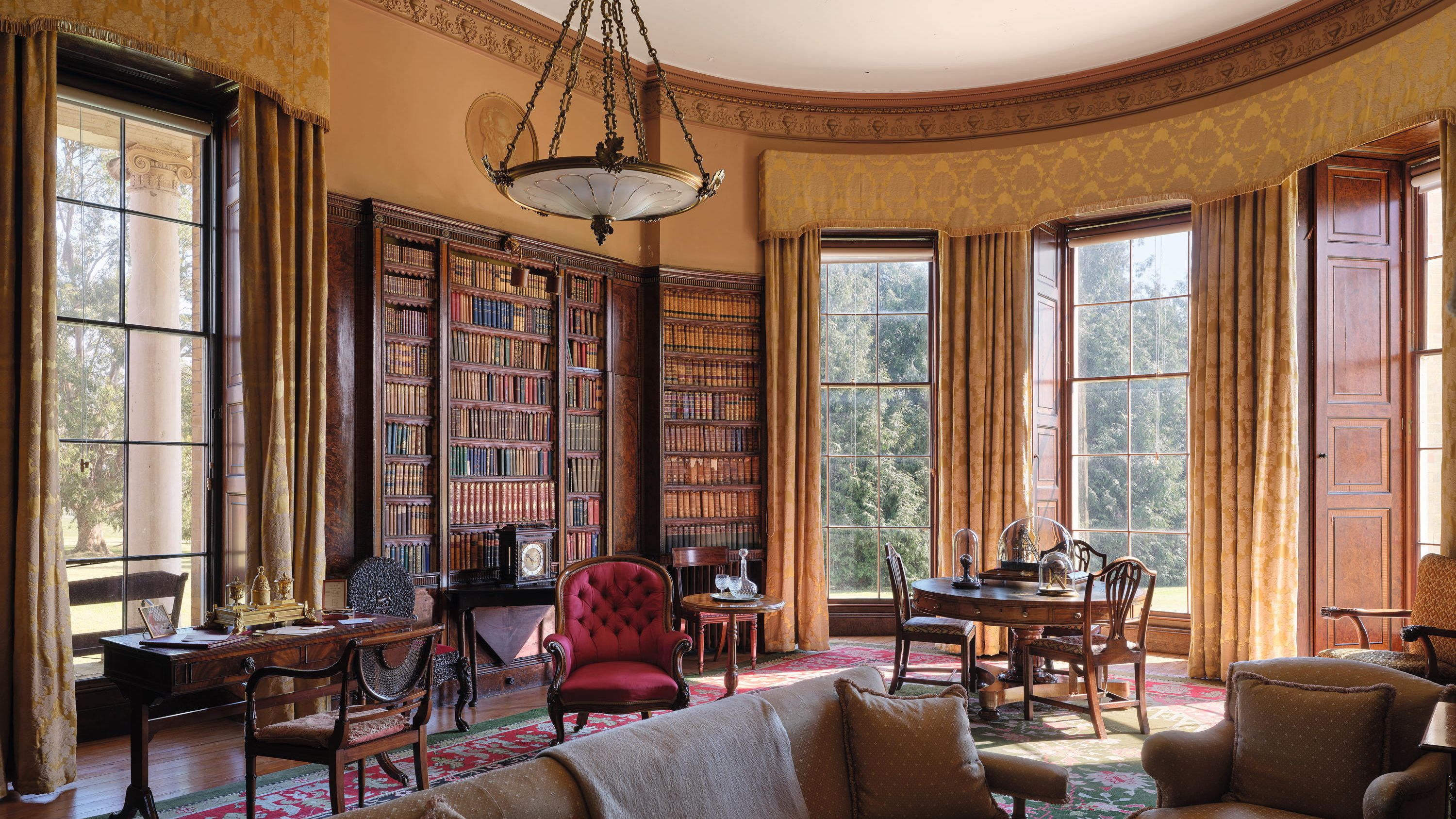

Fig 2: The library. It is semi-circular at either end and the colour scheme with grained bookcases is probably late 19th century.

Samuel Wyatt was surveyor to some large estates, including Thomas Coke at Holkham in Norfolk and Viscount Anson at Shugborough in Staffordshire, for whom he designed superb farm and estate buildings. He developed a distinctive neo-Classical style, simple and austere in comparison to James’s more flamboyant creations. Belmont, being well preserved and open to the public, is probably the best place to study the work of this under-appreciated Georgian. It was last described in Country Life on February 10, 2010, by John Martin Robinson, who elucidated its early history for the first time.

In 1769, Wilks bought land here and built a house: a simple Georgian box of red brick five bays wide, part of which survives within the service wing of the present house. In 1780, he sold the estate to Col John Montresor of the Royal Engineers, a distinguished career soldier — and it was he, along with Wyatt, who made Belmont a great country house.

The colonel massively extended the building to create the house in its modern form: between 1789 and 1793, he made six payments totalling £4,388 to Wyatt, who was evidently acting as principal contractor, as well as designer. Montresor’s story ended tragically: falsely accused of embezzling official funds in 1799, his property was seized by the Crown and he was committed to Maidstone prison, where he died before his case could come to trial. His sons spent two decades battling for posthumous justice; they eventually proved their father’s innocence and were paid compensation in 1822.

Fig 3: The dining room, hung with portraits, preserves its original table and 26 chairs. The superb carpet was commissioned by the 4th Lord and made in India in the 1890s.

The Belmont estate had, by then, long since moved on. It was auctioned at Garroway’s Coffee House in London in June 1801 and was bought by Gen George Harris (1746–1829). The general was a self-made man, the son of the curate of Brasted. He served in America in 1774–78 and, in 1790, was sent to India. As the military commander of the Madras presidency, he led the East India Company’s forces against Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore. In May 1799, Harris’s forces stormed Tipu’s capital, Seringapatam; his eldest son, William George, was also present at the siege, aged 17. Harris received the thanks of Parliament and an eighth share of the £150,000 prize-money, which probably furnished the purchase price for Belmont.

The general was created Lord Harris in 1815. A family man with several children, he retired to ‘live nearly 30 years at Belmont respected and beloved by his neighbours’, as the inscription on his monument in Throwley Church says. He died there in 1829. His son William George, who succeeded as the 2nd Lord Harris (1782–1845), also had a distinguished military career and was wounded at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. He was, in turn, succeeded by his son George Francis, the 3rd Lord (1810–72), who was Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Trinidad, in about 1846–54, and, later in the 1850s, Governor of Madras. His son George Robert, the 4th Lord, was Under Secretary for India, Under Secretary for War and then Governor of Bombay in 1890–95. Belmont was, therefore, the family home of a dynasty that spent long periods overseas and the building’s contents reflect this history.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Fig 4: One of the Coade-stone panels on the façade, complementing the Coade-stone capitals of the Ionic colonnade. A view of the house in low relief is clearly visible to the left.

The house is approached from the south and is asymmetrically planned. A three-bay main block to the right is fronted on approach by a colonnade of Ionic columns, the capitals made of Coade stone. To the left is the orangery, with a long row of tall windows, and beyond that to the left is the kitchen. To the right, around the corner, the east front is symmetrical, with a three-bay centre framed by two broad bow windows capped with shallow domes.

The three main rooms of the house — the drawing room, dining room and library — are incorporated within this frontage. It is ornamented by panels of sculpture also made of Coade stone, one of which depicts the house (Fig 4). What remains of the original building was incorporated by Wyatt into a service wing and now forms part of a pleasant and spacious courtyard to the rear. The other buildings around this courtyard formerly housed the stables, the brew-house, the Justice Room and a billiard room.

Fig 5: The drawing-room windows with their narrow bars are characteristic of Regency buildings, uniting the interior with its setting.

As enlarged by Wyatt, Belmont is very substantially built, with walls 3ft thick. The façades to the service court are of red brick, but the main house is a light buff colour, combining yellow bricks and ‘mathematical tiles’, a kind of cladding that resembles brick. It’s possible that some of these materials came from Holkham, where Wyatt worked. Slates for the roof came from the Penrhyn quarries in North Wales, owned by Richard Pennant, another of his clients, whose estate was managed by his younger brother, Benjamin Wyatt. The window sashes are large, with strikingly thin metal glazing bars.

Closer up, the scale of the conservatory windows is truly impressive.

Passing through the front door, the visitor enters a square entrance hall, which is simple and elegant, with a shallow vaulted ceiling. The lion and tiger in glass cases were shot in India by the 4th Lord Harris when Governor of Bombay. Another of the house’s themes — the great collection of timepieces formed by the 5th Lord — is introduced by three superb English longcase clocks.

Beyond the hall is the high saloon or staircase hall and behind that a corridor, spanned by arches, which form a central axis through the house. To the right of the entrance hall is a door to the drawing room (Fig 5), lit by a bow window and with gently curved ends, a feature that Wyatt often used. The room was redecorated in the 1930s for the 5th Lord by the decorator Basil Ionides, with fine curtains of white-painted silk and striped wallpaper. Its gilded pier glasses and pelmets date from the early 1800s.

Fig 6: A view of the stair hall. There are two upper landings in this lofty space. The room contains several outstanding clocks.

Fig 6a: A hobby horse with a view, overlooking the hall and the portraits on the first floor landing.

Beyond is the dining room (Fig 3), which occupies the centre of the east front and has walls of ochre-red and white from a 1950s redecoration, as well as a fine collection of furniture supplied for the room in the 1830s. This includes 26 chairs with leather seats and a huge table. The splendid carpet is one of several in the house that were made in India in the 1890s, commissioned by the 4th Lord. This interior is dominated by full-length portraits, including a family group by Arthur William Devis, of the 1st Lord and Lady Harris, with their large family.

The library, which corresponds to the drawing room at the opposite end of the building, is also curved at both ends and furnished as a comfortable sitting room (Fig 2). There are signs that the upper walls were once a yellow ochre with grisaille-painted panels that represent fictive sculptural reliefs. It is likely that the bookcases were formerly painted white. The room was redecorated, however, probably in the late 19th century, when the bookcases were grained to resemble walnut and the upper walls painted a tobacco colour.

A room overlooking the back courtyard has recently been adapted as a fine exhibition space for the magnificent collection of Indian arms and armour, dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries, including weapons captured during the Seringapatam campaign.

Fig 7: One of the principal bedrooms at Belmont House.

The high, top-lit saloon or staircase hall (Fig 6) rises through three storeys, although, from the outside, Belmont seems to be two storeys high. A cantilevered stone stair with an iron balustrade winds around three sides of the hall to a first-floor landing and corridor leading to the main bedrooms (Fig 7).

Above this is another gallery. The attic spaces off it were used as store rooms, rather than bedrooms, although visiting servants seem to have been housed up there. One of the twin domes has a little viewing gallery, from where there is a fine prospect over the park and the countryside, towards the sea at Whitstable.

In 1980, the 5th Lord Harris formed The Harris (Belmont) Trust to own and care for the house and park. On the death of the 6th Lord in 1995, the rest of the 3,000-acre estate was transferred to the trust, ensuring its financial stability. Since then, the house’s remarkable collections, many of which were found stored in the attics, have been conserved and, if possible, displayed.

Visitors are welcome these days at Belmont House, which is 'managed by its trustees and staff with exemplary care and sensitivity'.

They touch on many and varied themes associated with the family. A portrait on the staircase of the 4th Lord, standing at the wicket in cricketing flannels, represents one of these; he captained the Kent team for 16 years, played against Australia at Lord’s on numerous occasions, and introduced Test cricket to India. Two bedrooms house a superb collection of watercolour landscapes of Trinidad by Michel-Jean Cazabon (1813–88), an artist of French and African descent who was trained in France and returned to Trinidad. The paintings were commissioned by the 3rd Lord Harris when Governor of Trinidad and constitute a unique record of the island in the mid 19th century.

Visitors will have noticed that every room in Belmont contains fine clocks. All these were acquired by the 5th Lord (d. 1984), who made the finest private horological collection in the UK, numbering 340 English and French timepieces from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. Two further bedrooms have been converted into a clock museum and the house offers specialist tours. Indeed, many visitors come specially to see the clocks, the armoury collection or the Cazabon views.

The beautiful grounds, including a walled garden and kitchen garden, form a major attraction in themselves. Nearby is the cricket pitch, established by the 4th Lord, which hosts regular games. The wider parkland was landscaped in the style of Humphry Repton. The surrounding estate is in the Kent Downs National Landscape: it includes 44 houses and cottages, 50 acres of orchard, 700 acres of broadleaf woodland and a 1,700-acre arable farm, managed in-hand. The estate also maintains footpaths and holiday cottages.

Belmont thus remains in good heart, managed by its trustees and staff with exemplary care and sensitivity, and is regularly open to the public with the help of volunteers. It is a jewel in Kent’s celebrated crown of historic houses and gardens.

Visit the Belmont House website to find out more about the house and visiting.

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Country Life — here's how you can subscribe to Country Life magazine.

Steven Brindle is an author, historian and holds the title of Inspector of Ancient Monuments at English Heritage.