Heaven in Devon: The sophisticated, ethereal beauty of Exeter Cathedral

Exeter Cathedral in Devon is an idiosyncratic masterpiece that illuminates the sophistication and personalities behind the development of late-medieval English architecture. John Goodall explains more, with photography by Paul Highnam.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Some 1,000 years ago, in 1050, a priest of the Chapel Royal called Leofric was installed as the first Bishop of Exeter. Little is securely known about his background beyond the fact that he was Brytonicus — British — and probably born in Cornwall. Leofric was educated in Lotharingia and in uncertain circumstances became a chaplain to the future English king, Edward the Confessor, then living in exile in Normandy. When Edward returned to England and ascended to the throne in 1043, he used the institutions of the church as a means of imposing control on the kingdom. Leofric was a beneficiary of this policy and Exeter Cathedral one of its products.

Leofric’s new cathedral replaced two predecessors — in Crediton, Devon, and St Germans, Cornwall — and established his authority in the most important centre of population, administration and trade in the region. Exeter was in origin a legionary fortress established in about AD55 at the lowest crossing of the River Exe. It quickly developed into a regional capital of the territories of the Dumnonii tribe, but, from the 5th century, was seemingly abandoned as a settlement. By about 670, as the area was absorbed within the Kingdom of Wessex, a Benedictine monastery was founded within the Roman walls and it was here that one Wynfrith — the future St Boniface — was educated.

Fig 1: The west front of Exeter Cathedral. Its screen of sculpture was once painted.

Then, in the face of the Viking incursions in the 9th century, Exeter became a fortified settlement or burh. Consequently, in 932 — a date given by long tradition — the monastery was re-founded on a grander scale by King Aethelstan, who probably rebuilt its church. This stood to the west of the present cathedral and later became a parish church, St Mary Major, since demolished. Leofric appropriated Aethelstan’s church as his new cathedral and replaced its community of monks with a group of 24 priests — termed canons — living communally under the quasi-monastic Rule of St Chrodegang, Bishop of Metz (ruled 742–66).

This choice of regimen was highly significant and suggests Leofric’s active engagement with the church reform movement then sweeping continental Europe. Not until the Norman Conquest of 1066 would the rest of the English church be fully exposed to its transformative effects, which usually combined institutional reform with architectural reconstruction. Exeter’s early links to the former, however, may explain why the latter came surprisingly late, during the reign of the third bishop of the see, Warelwast, another royal clerk, diplomat and vigorous reformer. According to the Annals of Tavistock, the new cathedral was begun in 1114 and the canons entered their new choir in 1133. Work to the nave continued late into the century.

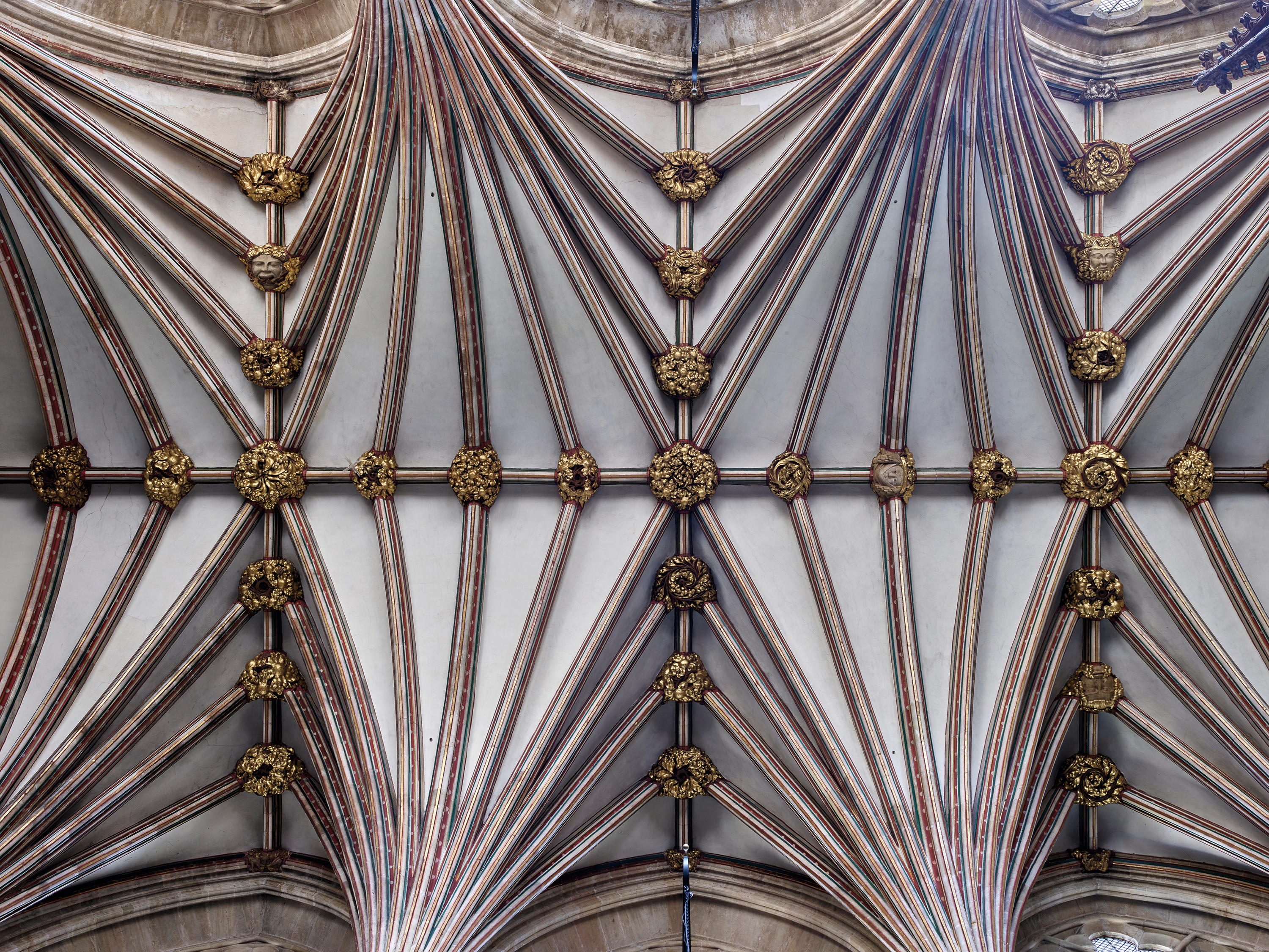

Fig 2: The interior of Exeter Cathedral, with its staggeringly dense ornament.

The Romanesque church occupied a fresh site and was laid out on cruciform plan with the flanking transepts heightened as towers, a unique arrangement. These twin towers survive and give the cathedral its distinctive outline. Set on tall bases of cut stone, they grow in ornament as they rise upwards. Both are presumed to have had low spires; that to the north was remodelled in the 15th century.

The unusual form of the transepts meant that the interior did not have a conventional crossing, where the four arms of the church intersected. Rather, the arcades that divided the interior into a central vessel with flanking aisles ran unbroken through the full length of the building. We know from archaeological excavation in 2023–24 that both aisles terminated to the east in semicircular apses, as well as that the high altar stood in a larger apse that projected beyond these. This was externally faceted — with up to 11 sides — and incorporated a curved internal passage or ‘ring crypt’ beneath the level of the high altar. The best parallels for these arrangements are to be found in Anglo-Saxon churches, such as Wing, Buckinghamshire.

Fig 3: The north front. The squat, castle-like out-line is busy with towers and battlements.

It is likely the cathedral was vaulted in the manner of other great churches in the South-West, such as Gloucester Abbey, and a surviving capital proves the piers were of massive proportions. In places, contrasting colours of masonry were banded for decorative effect. As we shall see, the Romanesque church shaped the present building.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By the early 13th century, Leofric’s original constitution of the cathedral community looked eccentric. To make it conform to arrangements in other cathedrals, Bishop Brewer introduced a governing Dean and Chancellor in 1225. As was also usual elsewhere, the canons began to live in their own houses and appoint vicars or deputies to assume their regular duties. In expression of this institutional change, the choir was refurnished; some of the misericords from the stalls survive. A chapter house was also constructed beside the south transept and linked to the church by a cloister walk.

The Romanesque church seems to have remained intact until the 1270s, when a prolonged reconstruction programme got under way. Over the course of the next century — and driven forward by five active bishops — the cathedral that we see today came into being. It is a remarkably coherent creation in aesthetic terms and our understanding of it is informed by an exceptionally full run of surviving fabric accounts. Even with many gaps, these documents offer the most complete record of the rebuilding of a medieval cathedral in Europe.

Fig 4: The Lady Chapel, which was begun in the 1270s. Inspired by French example, English masons were fascinated by the decorative possibilities of window tracery.

Construction began at the east end with the demolition of the turning bays of the Romanesque choir. Its rubble was used to level the ground to the east of the high altar and three chapels, the largest dedicated to the Virgin (Fig 4), were laid out. The figure responsible was Bishop Bronescombe (ruled 1257–80), who requested burial here and whose remarkable tomb — modernised in the 1400s — survives (Fig 6). It is one of many important monuments in an exceptionally fine collection.

Work gathered pace through the generosity of Bishop Quinil (ruled 1280–91). He was described as ‘the first founder of the new work’, probably because he began the main volume of the eastern arm. It was under his successor, Thomas de Bytton (ruled 1292–1307), however, that this structure was vaulted and glazed. The operation was conducted from at least 1297 by Master Roger and reflects a technical knowledge of other major building projects across the kingdom, notably Lincoln Cathedral and Old St Paul’s, London.

The new choir differed from its Romanesque predecessor by terminating behind the high altar in a flat wall inset with a massive eastern window. This probably first incorporated a central rose, but was renewed in its present form in the late 14th century. The internal elevations once comprised an arcade dividing the central vessel from the aisles at ground level, below tall clerestorey windows. Over all was a stone vault and the inner arches of the tower transepts were opened out to create a more conventional crossing.

Fig 5: The sedilia, with painted cloths in each seat. The lost altar reredos was richly gilded and crowned with similar canopies.

Other great churches of the 13th century, such as Salisbury, Wiltshire, accommodated side altars in a second pair of eastern transepts flanking the choir. At Exeter, however, these transepts are reduced to small chapels opening off the aisles.

By comparison with contemporary Gothic churches in France, the new cathedral was astonishingly low built. What it lacked in height, however, it made up for in density of carved ornament and colour. Every surface ripples with mouldings and the masonry combines pale limestone with blue-grey Purbeck marble. The vault is not only articulated by a uniquely dense clustering of ribs — 13 rising from each spring — but large and richly carved bosses that still display their medieval paint (Fig 8). There is also an extraordinarily varied display of inventive window tracery patterns, a particular fascination of English masons in this period.

In 1310, Master Roger was succeeded by William Luve, but, by 1316, during the rule of Bishop Stapeldon (1308–26), another mason, called Thomas of Witney was in charge of the building operations. Thomas is first documented at Exeter in 1313 advising on the design of a monumental timber canopy that oversails the bishop’s throne in the choir. Executed in wood and rising to the vault with tiers of sinuous and interpenetrating forms, it is one of the masterpieces of European medieval architectural joinery (Fig 7).

Fig 6: Bishop Bronescombe’s gilded tomb.

The form of the canopy reflects Thomas’s earlier documented experience working on the choir at Winchester cathedral priory and St Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster, (Country Life, April 1, 2015). The latter was one of the defining buildings of the English medieval architectural tradition. It not only pioneered the miniaturisation of complex architectural forms in church furnishings, but the free integration of materials — masonry, timber, glass, sculpture and paint — to symphonic structural and decorative effect.

It was presumably also on Thomas’s advice that the two-storey internal elevations of the new choir were ingeniously enriched with a triforium level. This was contrived within the base of the clerestory and gave the building three horizontal registers, an arrangement typical of the greatest English churches. From 1316, Thomas erected a sumptuous reredos with a matching sedilia behind the high altar. Only the latter now survives (Fig 5) to evoke the complexity and opulence of the whole. No less remarkable is his surviving pulpitum screen dividing the choir from the nave and erected in 1318–25.

By 1324, the purchase of stone suggests that plans for rebuilding the nave were in train. Work only got under way, however, in 1328, with the dedication of the high altar and the appointment of Bishop Grandisson, whose unusually long rule, from 1328–69, would witness the effective completion of the cathedral. Bishop Grandisson worked closely with Thomas of Witney, whom he described as a ‘dearly loved member of our household’. He also wrote — separately — of Thomas’s ‘industry [as being] of special value for the repair and in part new building, by his skill, of the fabric of our church of Exeter’.

Fig 7: The lofty choir and soaring canopy over the bishop’s throne.

The Romanesque nave was gutted and its aisle walls reduced to the level of the window sills. Within this low shell, the new nave was created. Thomas borrowed all its forms from the choir, creating the imposing and coherent interior that confronts the modern visitor (Fig 2). A north porch gave day-to-day access to the nave for the laity. It corresponds internally to an arcade arch flanked by niches, probably for figures of the church’s patrons, St Peter and the Virgin. High above is set a balcony ornamented with angels playing instruments, presumably a musicians’ loft.

Externally, Thomas’s works were austerely detailed, making use of simplified mouldings and forms from castles, such as battlements and arrow loops. It is as if he wished the cathedral to read outwardly as a heavenly city encircled by fortifications (Fig 3).

Thomas is last mentioned in the cathedral accounts in 1342 and was replaced by another outstanding designer, William Joy, master mason of Wells Cathedral. It was undoubtedly Joy who undertook work for Bishop Grandisson to the nearby collegiate foundation of Ottery St Mary, a remarkable homage in miniature to Exeter Cathedral (and Wells).

Fig 8: The high vault of the choir is densely ornamented with narrow ribs and richly carved bosses. Some medieval colouring survives.

At Exeter, the handover between Thomas and Joy coincided with work to the west front, which was reared on the foundations of its Romanesque predecessor (Fig 1). It is to Thomas that we owe the design of the great west window, which is undoubtedly indebted to St Stephen’s Chapel, Westminster. Also buried in the fabric is evidence of the lower section of the gable wall he created, which comprised a large central door flanked by two blind arches and two smaller side doors.

Bishop Grandisson, however, wanted to rest within the west front he had completed, so Joy placed his burial chapel to the right of the central door and added the first part of a screen wall across the front of the building to accommodate it. Confusingly, what now seems like a coherent structure was actually built and densely furnished with sculpture over the course of a century. Once brightly coloured, these accessible and animated figures have, incredibly, survived iconoclasm.

The cathedral interior continued to evolve through the late Middle Ages. Its rich collection of chantries and furnishings assumed a distinctive vocabulary of forms that were widely copied in the region. Also preserved here is an unusual quantity of medieval painting. The Reformation, the Civil Wars of the 1640s and an air raid in 1942 all left their mark on the cathedral fabric, as did a major restoration in the 1870s under the direction of Sir George Gilbert Scott. It is to the latter, and another ambitious project of renewal completed this year in the choir and cloister, that we will turn in the next article.

Visit the Exeter Cathedral website to find out more about visiting.

Acknowledgements: John Allan

This feature originally appeared in the December 10, 2025 issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.