'The Shakespeare of architects... he has yet had no equal in this country': Sir John Vanbrugh and the legacy of Blenheim Palace

To mark the tercentenary of Sir John Vanbrugh’s death, Charles Saumarez Smith considers the changing reactions to one of his greatest creations, Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire. Photographs by Will Pryce for Country Life.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sir John Vanbrugh was a successful playwright who turned himself into an even more successful architect. His achievement in both respects was deeply improbable given what we know of his unsettled early career in business, the army and as a prisoner in France. That in turn, however, may help explain why, in architecture, he was not an orthodox Classicist, but viewed his buildings in free and abstract terms, intending them to evoke an emotional, as much as an intellectual response. During his lifetime, this approach was regarded with suspicion if not hostility, but, a century later, in the high noon of Romanticism, it came to be admired, particularly by architects, for its originality, its extreme vigour and its compositional freedom.

On the tercentenary of his death, it is worth exploring this profound shift in critical attitude through the prism of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, which was famously built for the Duke of Marlborough to celebrate his triumph at the Battle of Blindheim in 1704. From the outset, Vanbrugh had his critics. The Duchess of Marlborough and Queen Anne both wanted Sir Christopher Wren to take on the project and, when the Earl of Ailesbury was shown the designs in September 1705, he thought ‘(by the plan I saw) that the house is like one mass of stone, without taste or relish’. When construction began in the summer of 1705, visitors to the site began to express their opinions about the building. They were not always consistent in their views.

Fig 2: ‘The most expensive and unnecessary bridge ever built’ leads to the house.

One such was the Duke of Shrewsbury, who was regarded as an architectural expert, having been educated in Paris in the 1670s and spent nearly four years in Rome. He wrote two letters to the Duke of Marlborough after visits in May and August 1706. In both, he was enthusiastic about the gardens, which were ‘so noble, and as far as I can discover at the first view, so perfectly well layd out, that they will far surpass any thing I have seen in England’.

Progress to the house (Fig 1), by contrast, made it harder to judge. On his second visit, Shrewsbury described the private wing ‘raised to almost the top of the windows of the first storey’, venturing that ‘the stone work without seems very strong and beautiful’. He was not, perhaps, otherwise impressed because, when he came to choose an architect for a nearby house at Heythrop, he turned not to Vanbrugh, but Thomas Archer. Added to which, according to Alexander Pope, writing in 1717, it was Shrewsbury who coined the phrase that Blenheim was ‘a great Quarry of Stones above Ground’.

Fig 3: The monumental entrance hall is presumably one of the fine internal ‘vistas’ remarked upon by Alexander Pope, who called the spaces ‘very uselessly handsome’.

It was not only friends of the Marlboroughs who came to inspect the building work at Blenheim, but tourists. In September 1710, Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach, a German bibliophile, visited and wrote a long critique of it. He was told that the building had already cost £800,000, a grotesque exaggeration, but an indication that the immense cost of the project was a topic of both widespread discussion and criticism. He was impressed by the scale of the project and number of people at work — he reckoned 800; it reminded him of the Tower of Babel.

He went on to observe: ‘At a distance or from the side it makes a poor impression on account of its many terraces, turrets and other features’, but thought it ‘uncommonly imposing, when viewed from in front’. Otherwise, the building struck him as ‘very low because of the quite extraordinary strength and thickness of the walls and decorations’ and he thought the ‘rooms, although very numerous, are all extremely small, and the windows, which are all high up as in a church, are also very small and seem still smaller on account of their height’.

What really impressed von Uffenbach, however, was the bridge being constructed in front of the house (Fig 2): ‘This must be the most expensive and unnecessary bridge ever built in the world… The bridge is entirely composed of squared stone of prodigious proportions and… consists of three arches, the centre one of which is a hundred feet long and forty feet high, an astounding size.’ Other visitors responded similarly. Thomas Cave, a reactionary Tory MP and owner of Stanford Hall in Leicestershire, visited in September 1711 and dismissed Blenheim as ‘a great house with little rooms and less for cost; the gardens are large and in good order but not the prettiest; there are some foreign Statues and Marbles very Curious but not set up’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Fig 4: One of Sir John Soane’s drawings of the north front he prepared for his Royal Academy lectures as professor of Architecture.

The following year, Samuel Molyneux, a recent graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, wrote that: ‘The grand Portico is in my opinion Clumsy and Crowded. The several Towers in the building extreamly Gothick and Superfluous, The great Face to the Avenue surprizeingly odd in my Opinion.’ Molyneux did at least allow that the house had some virtues if viewed from a distance, describing how ‘upon the whole, I must confess this front at a Distance where its minuter Faults and virtues are not discernible does indeed appear noble and magnificent enough.’

The most brutal criticism of Blenheim during Vanbrugh’s lifetime, however, came from Pope, who was a political enemy and inclined to waspishness. After a visit in 1717 he wrote: ‘I never saw so great a thing with so much littleness in it… When you look upon the outside, you would think it large enough for a prince; when you see the inside, it is too little for a subject, and has not conveniency to lodge a common family. It is a house of entries and passages; among which there are three vistas through the whole, very uselessly handsome… In a word, the whole is a most expensive absurdity (Fig 3).’

Visitors to Blenheim were inclined to be more generous once it had been completed. For example, Daniel Defoe viewed it in 1724 as Vanbrugh had intended, not as a private house, but a national monument, a source of patriotic pride: ‘The magnificence of the building does not here as at Canons, at Chatsworth, and at other palaces of the nobility, express the genius and the opulence of the possessor, but it represents the bounty, the gratitude, or what else posterity pleases to call it, of the English nation, to the man whom they delighted to honour.’ William Stukely, the antiquarian, writing the same year, likewise saw it as ‘a vast and magnificent pile of building, a royal gift to the high merit of the invincible duke of Marlborough’.

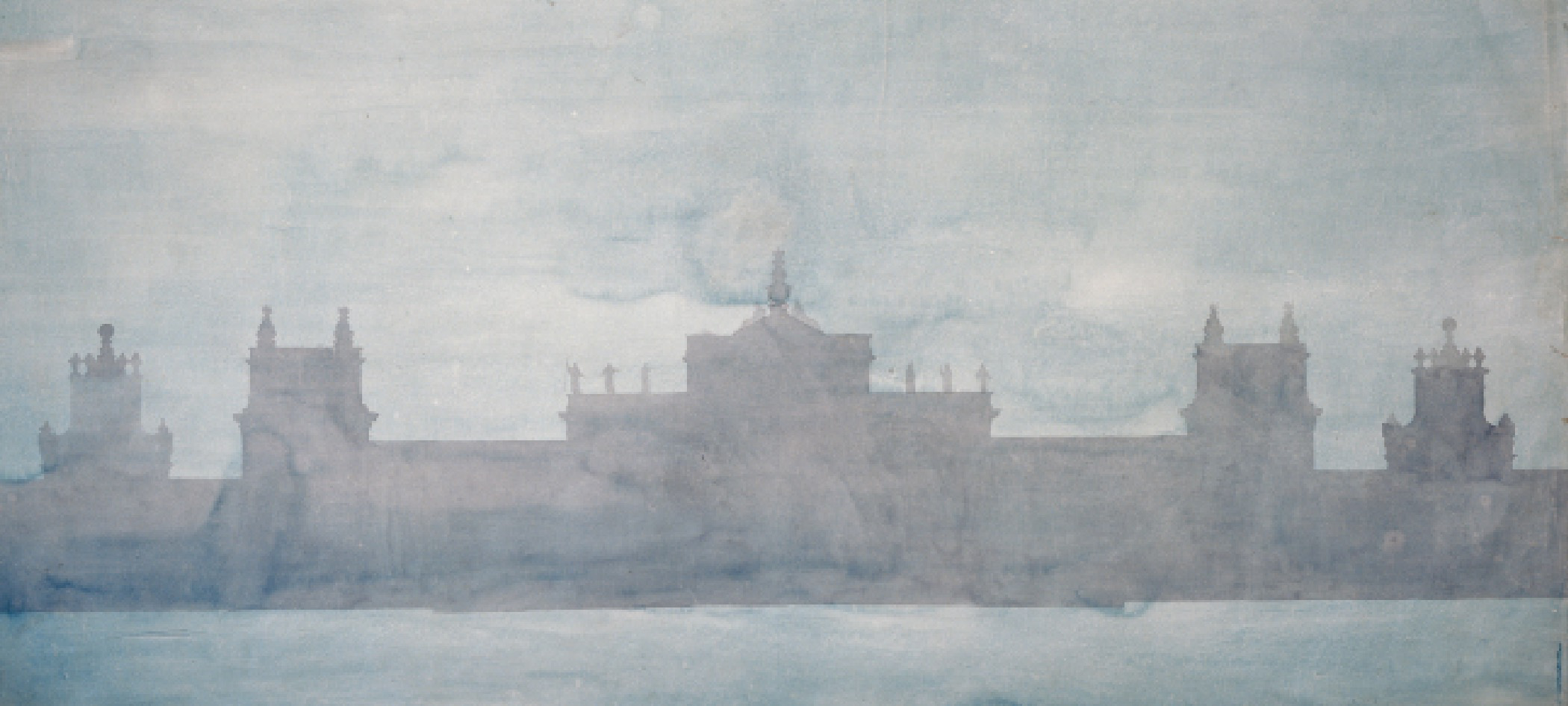

Fig 5: The second view of Blenheim that was prepared by Soane. It shows the façade without detail, but articulated by shadow.

Even so, in the early 18th century, although many admired the park, they found the scale of the house indigestible. As Lady Hervey wrote in 1748, it was an ‘emblem of him for whom it was built — an edifice that ornaments the country, but has plundered the people; — a great house, but not a good one’.

Intriguingly, that began to change immediately Vanbrugh died in March 1726. In a joint preface to their Prose Miscellanies, Jonathan Swift and Pope wished that their ‘Raillery, though ever so tender, or Resentment, though ever so just, had not been indulged… Sir John Vanbrugh… was a Man of Wit, and of Honour’. Admittedly, this was about Vanbrugh’s virtues as a playwright, not as an architect, but it is often hard to disentangle the two.

What was it that caused the revival of Vanbrugh’s reputation? The first sign of a change in attitude to his work came from Robert Adam’s younger brother, James, who held forth — it appears rather boringly — about the compositional virtues of Blenheim when he was travelling back to Edinburgh with Alexander Carlyle, John Home and William Robertson in April 1758. ‘Though he did not say that Sir John Vanbrugh’s design was faultless, yet he said it ill deserved the aspersions laid upon it, for he had seen few palaces where there was more movement, as he called it, than in Blenheim.’ Writing with his brother in their Works in Architecture, Adam described Vanbrugh as ‘a great man, whose reputation as an architect has long been carried down the stream by a torrent of undistinguishing prejudice and abuse… [His] genius was of the first class; and in point of movement, novelty and ingenuity, his works have not been exceeded by anything in modern times’.

In some ways, one can see why the Adam brothers, eclectic and interested in the Picturesque and castle building, admired Vanbrugh. More surprising is the fact that their contemporary and rival William Chambers also spoke well of him in what was to have been a series of lectures at the Royal Academy in the early 1770s: ‘The French and the Italians,’ he wrote, ‘have a method of rendering the most trifling composition considerable, which Vanburg alone amongst the English has ventured to imitate… however faulty Vanburg may have been in other respects, it is certain that his method of decorating the chimney shafts, raising turrets and surrounding his buildings with terrasses, bastions, gates, obelisks, etc. the like gives an air of grandeur and novelty to his compositions that will always be admired by men of true judgement.’

One can see this change in taste reflected in the writings of Horace Walpole, who was always alert to changes in public attitude. When he first published his Anecdotes of Painting in England, Walpole simply reproduced George Vertue’s damning words about Vanbrugh: ‘He wanted eyes, he wanted all ideas of proposition, convenience, propriety. He undertook vast designs, and composed heaps of littleness… he broke through all rule, and compensated for it by no imagination.’

However, 10 years later, Castle Howard in North Yorkshire bowled him over. He saw: ‘A palace, a town, a fortified city, temples on high places, woods worthy of being each a metropolis of the Druids, vales connected to hills by other woods, the noblest lawn in the world fenced by half the horizon, and a mausoleum that would tempt one to be buried alive, in short, I have seen gigantic places before, but never a sublime one.’

The artist Sir Joshua Reynolds, a friend of Walpole, picked up on the idea that Vanbrugh was good at composing buildings from a distance as if he was a painter in his 13th Discourse to the Royal Academy of 1786. He praised Vanbrugh’s ‘originality of invention’ and added how ‘he understood light and shadow, and had great skill in composition’. The comments are unexpected because Reynolds did not pretend to be an architectural critic and, indeed, there are very few references to architecture in his writings.

'For invention he has yet had no equal in this country': Blenheim Palace today is seen as Vanbrugh's crowning glory, and attracts tens of thousands of visitors each year.

This was the critical milieu the young John Soane must have enjoyed as an early student at the RA Schools. Many years later, speaking as the RA’s professor of Architecture in January 1810, he declared Vanbrugh ‘the Shakespeare of architects’ and went on: ‘We must not seek in his work the simple elegance of the antique. He possesses a great portion of the fire and boldness/power, force, expression, marked character, of Michelangelo and Bernini, but he wants the softness and delicacy of Palladio… for invention he has yet had no equal in this country.’

Soane arranged for his lectures to be illustrated with big watercolours prepared by his office. These include three different images of Blenheim, which were prepared, presumably as a sequence, to show the way Blenheim was massed. The first (Fig 4) was a relatively conventional view, the second (Fig 5) shows the building half abstracted, possibly to draw attention to the way it had been composed. In the third (Fig 6), all detail is dissolved, the building appears as a ghostly image in outline viewed from a distance as a free composition. These three images give a clear view of what it was Soane was encouraging his students to look at and admire — the sense of a building as a free and abstract composition, dominated by an idea of mass, with the power of evocation entirely independent of orthodox classicism. These are still qualities we admire in Vanbrugh.

Visit The Blenheim Palace website. Charles Saumarez Smith’s new book ‘John Vanbrugh: The Drama of Architecture’ (Lund Humphries, £29.99) is out now. ‘Vanbrugh: The Drama of Architecture’ runs at the Sir John Soane Museum, London WC2, from March 4–June 28 www.soane.org

This feature originally appeared in the January 14, 2026 issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.

Charles Saumarez Smith is an architectural historian, writer and curator. As well as his books, articles and lectures, he has been director of the National Portrait Gallery, director of the National Gallery, chairman of The Royal Drawing School, a trustee of the Garden Museum and the Castle Howard Foundation, an Honorary Fellow of Christ’s College, Cambridge, and an Honorary Professor in the School of History at Queen Mary University of London.