A fate worse than demolition? The desecration of the original Bank of England, one of Georgian architecture's great masterpieces

This year is the centenary of the enlargement of the Bank of England initiated by Sir Herbert Baker. Clive Aslet asks whether the project deserves its reputation as an unforgivable act of architectural desecration. Photographs by John Goodall.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the garden of Owletts, Kent, stand two Corinthian capitals conjoined as a bird bath. They form an architectural trophy from the old Bank of England that Sir Herbert Baker, the owner of Owletts, largely rebuilt in a campaign of work that began a century ago this year. Baker’s Bank (Fig 1) is the most prominent of all the numerous City financial institutions that were rehoused on a vastly bigger scale in the 1920s. Rather than enhancing his reputation, however, the project has stained it. That is because few architectural historians have been able to forgive the fact that the building he altered was the outstanding masterpiece of the Regency architect Sir John Soane.

Baker’s work, therefore, has been added to a charge sheet of other perceived failings, not least his refusal to change agreed plans for the Secretariat buildings in New Delhi in India to favour Sir Edwin Lutyens (who famously claimed in consequence to have met his ‘Bakerloo’). Yet is his vilification as the destroyer of Soane’s exquisite interiors of the Bank fair?

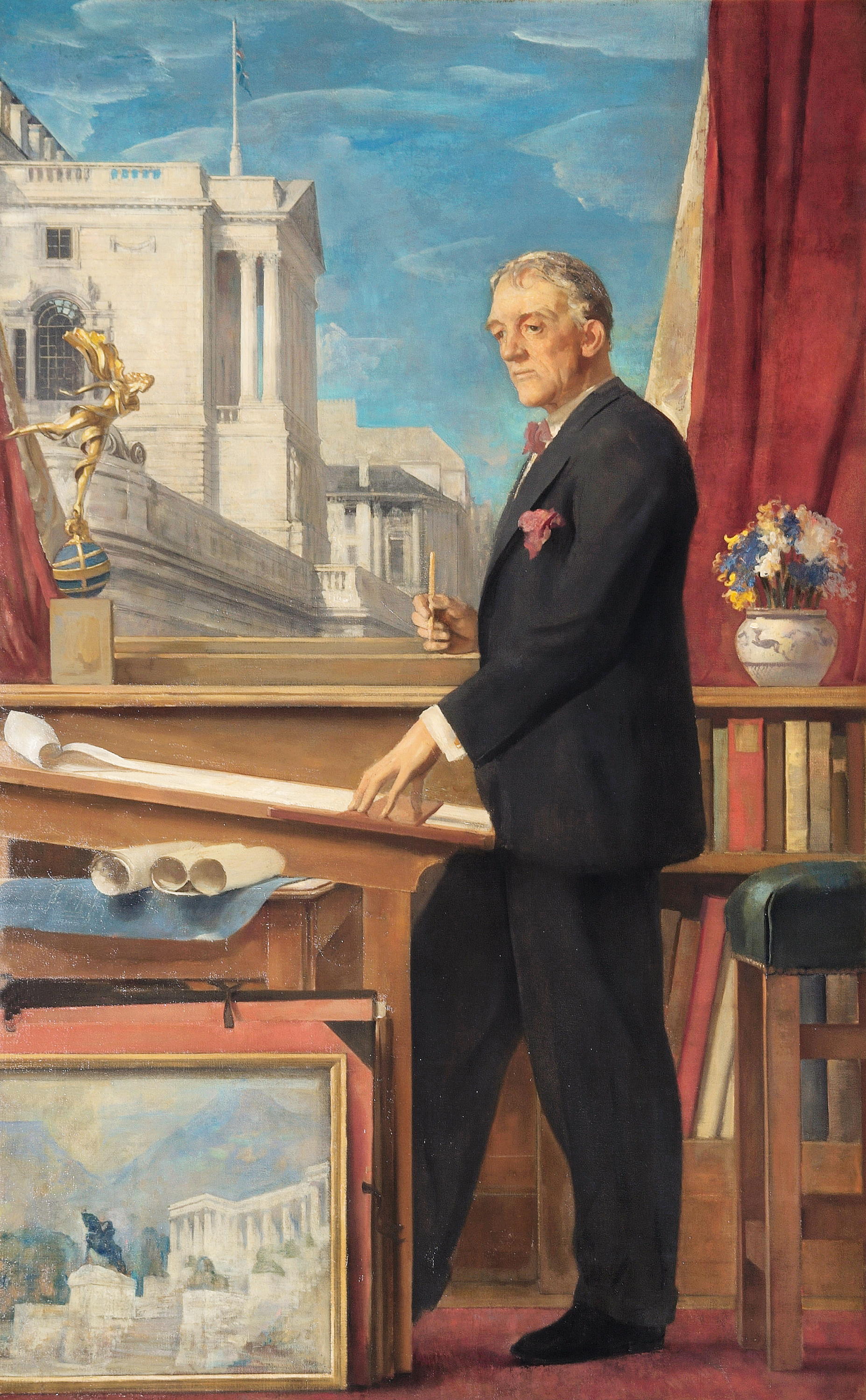

Fig 2: Alfred Kingsley Lawrence’s portrait of Herbert Baker, showing the Bank of England behind and the Rhodes Memorial at his feet. The delicate golden statue known as ‘Ariel’ is to the left.

Founded in 1694, the Bank began life in the hall of the Mercers’ Company. In 1734, it acquired what may be the first purpose-built bank premises in the world. The original building was designed by George Sampson in the form of a Palladian townhouse and extended in the 1760s by Robert Taylor. Soane first came on the scene in 1788, five years before the outbreak of war with France. War always requires finance, as well as arms — indeed, it had been to help fund William III’s campaigns against Louis XIV that the Bank of England had been first called into being.

The Bank of England as it appeared in the early 19th century, from an engraving by Daniel Havell dated 1816, after Thomas Homer Shepherd.

Both Britain’s national debt and the number of people employed to manage it ballooned during the Napoleonic Wars and Soane was kept busy for 45 years. Nothing could have better suited his obsessive, introverted personality. A blank screen wall wrapped the whole of the 3½-acre site. Around this secure perimeter, Soane placed a sequence of rooms of different shapes, playing variations on the ideas familiar from his other work, in which Classical pilasters and domes are distilled to their essence. Because the rooms were only one storey in height, he could make free use of his beloved top lighting.

In the 1840s, a parapet with gunloops was erected to protect the Bank from the Chartist Riots. Otherwise, this gentlemanly, slow-moving institution — its turn-of-the-century secretary, Kenneth Grahame, found time to write The Wind in the Willows (1908) — had, in terms of its architecture, changed little by 1914. By 1900, the national debt had sunk back to 30% of GDP, but the First World War catapulted Britain’s financial institutions into a different era. The national debt soared from £650 million to more than £7.5 billion and the workforce more than trebled. Everybody agreed that the Bank of England needed more space. Most people also thought that it should stay on its historic site.

Fig 3: Soane’s beautifully detailed screen wall, which encircles the Bank.

Lutyens believed that he had been promised the job of rebuilding the Bank by its outgoing chairman Lord Cunliffe, but, if so, Cunliffe had overstepped the mark. Instead, the Bank’s trustees delegated the matter to a three-man Rebuilding Committee. Those who mourn the loss of the Soane interiors might cast them as philistines, but this is far from the case. They were a cultivated group and as alive to Soane’s merits as their contemporaries. One of their first acts, indeed, was to seek the opinion of the director of the Sir John Soane’s Museum.

In 1921, the committee approached Baker for a report. Baker was, in some ways, a more obvious choice as an advisor — and, in due course, architect — than Lutyens. He may not have been Lutyens’s equal as a master of abstract form, but, before the First World War, had built more than 300 buildings in South Africa, including the parliament or Union Buildings in Pretoria. This made him more experienced than Lutyens, who was, in any case, hampered by his reputation for being expensive and best at home with rich clients. At Delhi, moreover, Lutyens had not shown himself to be collegial. Baker, by contrast, was the team player par excellence, having captained as a schoolboy both the Cricket XI and the Rugby XV at Tonbridge, Kent. No wonder he got on better with committees and later described the Bank as the ‘glorious climax’ ofa career shared with ‘many happy collaborators’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Baker’s report, dated July 6, 1921, was thoughtful. The Bank of England was, he wrote, the ‘one palace-like building in the City’ and suggested that ‘conservatism’ — what we would call conservation — should be one of a trium-virate of guiding values in any changes that were made, alongside efficiency and architectural expression. A balance, he argued, could be achieved by keeping Soane’s work, which was largely on the perimeter of the site, and erecting a building of many floors in the middle. Such a scheme would enable the Court of Directors of the Bank to fulfil ‘its obligations as Trustees of a precious national heirloom,’ as well as meeting the needs imposed upon it by the war. The result would display the ‘Bank’s historical periods of growth during the two great wars of England’s history’ and contain ‘the elements of architectural dignity commensurate with the Bank’s position and destiny in the City and the Empire’.

Fig 4: Baker’s solution to redeveloping the Bank, constrained by the City, was to build upwards over the original site.

On investigation, the committee did not think that Baker’s proposal would provide enough office space. It called for a second report into the feasibility of a completely new building, on a site cleared of all the existing structures. That December, the architect argued against such an approach. It might have opened the way to what a later age might have called a glass stump: ‘Such buildings express quite rightly and often excellently, profitable business enterprise, but would not such expression be quite inappropriate for the Bank of England?’ Baker concluded that, because security considerations demanded the retention of the screen wall (Fig 3), it would be difficult for any architect to escape building, as Soane had done, around the edge of the site.

A totally new structure would be an exciting opportunity for ‘self-expression’, but he preferred a composite solution that blended old and new. This was accepted.

How could any architect have met the brief for expansion without inflicting damage on Soane’s creation? Baker persuaded the committee to maintain a measure of continuity with the past, emphasising, in the Architect’s Journal, May 6, 1925, the ‘utmost sympathy’ that they felt towards ‘the retention of every feature that could be incorporated without too great a sacrifice of the essential efficiency of the new working organism’. Unfortunately for Baker, the judgement of history has chosen to overlook both what he aimed to do and his attitude towards the building he inherited. Rather than preserving the essence of the Soane rooms, he is accused of ruining them by raising some of the floors and replacing worn-out domes with ones to the same design, but in reinforced concrete. Extra bays were added to the Bank Stock Office and a new lantern inserted.

Fig 5: The main entrance of the Bank. The great bronze doors are part of a series created by Charles Wheeler that extends right around the building. Wheeler was commissioned to design all the Bank’s architectural sculpture, from keystones to doorhandles.

Thus the sculptor Joseph Armitage took down and remodelled old ceilings, such as the one above Taylor’s Court Room (Fig 6), to incorporate in the Baker design. Like Soane, Baker, who visited Italy in 1923 specially to gain inspiration for his designs at the Bank, was steeped in the Classical tradition and his interiors would probably be applauded today if it had not been for what they replaced.

Outside, we may regret the mismatch between the portico of doubled columns that forms the centrepiece of the new Bank as it surges above Soane’s delicate screen wall (Fig 4). Nevertheless, Baker was successful in his aim of providing a building that sat well with the surrounding architecture, including other new commercial premises such as Sir Edwin Cooper’s adjacent National Provincial Bank and Lutyens’s Midland Bank Headquarters on Poultry.

In one of a series of portraits commissioned from Alfred Kingsley Lawrence to document the rebuilding of the Bank, Baker is shown as a well-tailored, aloof figure, his face craggy, his eyes seemingly misted by Imperial dreams (Fig 2). At his feet is a painting of the Rhodes Memorial at Cape Town — Baker was a man of Empire through and through — and confronting him is a golden female figure. It is now incorrectly known as Ariel because the Bank’s Governor, Montagu Norman, so persistently misnamed it that the title stuck. According to Baker’s unpublished description of the Bank decorative scheme, however, it represents the ‘magic power of Trust transmitting Credit over the world’. It is now to be seen presiding over Soane’s ‘Tivoli Corner’ — a feature modelled on the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli — at the junction of Lothbury and Prince’s Street. ‘Ariel’ is a reminder of what a generous patron of artists and craftsmen Baker was; the Bank of England represents 20th-century Britain’s single largest commission of architectural sculpture for a single artist.

Fig 6: Robert Taylor’s Court Room was re-created in the 1930s. This photograph was taken for Country Life in 1969 following the room’s redecoration. The colour image is a rarity for the magazine’s architectural pages at this time. Baker’s Empire Clock, made with his son, Henry, which hung over the fireplace has already been removed.

That artist was Charles Wheeler, a future president of the Royal Academy, who was then in his late thirties. The programme included massive bronze doors (Fig 5) (one of the wonders of the Bank today), keystones, portrait heads, carved owls, bronze censers, medallions, plaques, fireplaces, lion door-handles and balustrades in the form of lions with keys. Baker was at his best in designing this type of ornament. Whereas ‘Ariel’ stands in a popular tradition of lighter-than-air statues, such as that known as Eros in Piccadilly Circus (1892) and the gilded ballerina on top of the Victoria Palace Theatre, opened in 1911, some of the work was avant-garde.

The unveiling of the giant stone figures of ‘Guardians’ and ‘Bearers of Wealth’ beneath the pediment was greeted, according to the Daily Mail, with cries of ‘Epstein!’ — a reference to Jacob Epstein’s unidealised nude sculptures on the British Medical Association’s building in the Strand, which had been stridently condemned as indecent when the public first saw them in 1908. Wheeler acknowledged his debt to Baker in a letter written on his 82nd birthday which begins ‘Dear Parent Oak’ and is signed ‘Sapling’.

In Baker’s day, the Bank of England, as yet unnationalised, was open to all. Now the only part that can be visited by the public is the Museum, occupying a reconstruction of Soane’s Bank Stock Office. This displays examples of the decoration that would once have delighted the public: tiles painted with stylised lions and a modern interpretation of Britannia; air vents incorporating the keys so necessary to a building in which gold bullion is kept; mosaic pavements by Boris Anrep, also known for his work at the National Gallery; and parts of the Empire Clock that once graced the Court Room. Installed in 1939, the clock served both as a demonstration of Baker’s modernising traditionalism and an Imperial world view that would soon seem outmoded. Symbols around the dial reflected the time zones of Imperial territories across the world. Baker’s engineer son, Henry, collaborated with the Synchronome Company on the mechanism, operated by a master clock next door. Alas, the Empire Clock was at some forgotten point taken down and most of it is now lost. However, a version of it survives at Owletts, as well as one at Winchester College.

Well versed in the Classics, Baker could face change with the stoicism of the Ancients. ‘Lately we were a sight for the bankers, now we are a pleasure for the birds,’ reads a translation of the Latin epigram that he penned for his Corinthian bird bath. ‘Which is the better fate?’

This feature originally appeared in the November 26, 2025 issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.