The Houses of Guinness: A real-life 'Succession' with privileged characters, living extravagant lifestyles 'and revelling in their extraordinary lives'

The Guinness family has garnered more headlines, column inches and pages written about them than they've seen for many years. Adrian Tinniswood's book, centred on the country houses they built in the British Isles, is the best of the lot, says Timothy Mowl.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

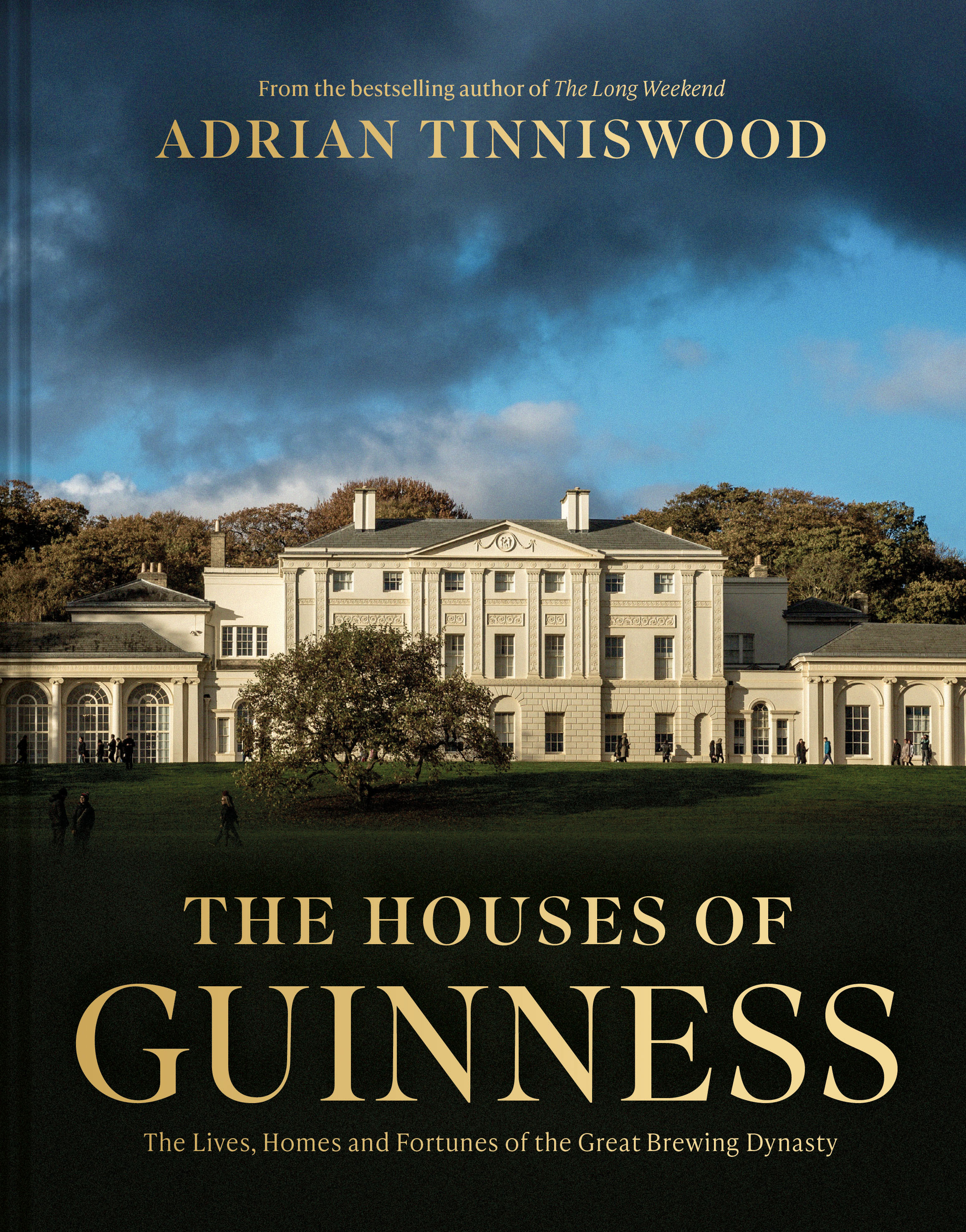

It might be true that you can't judge a book by its cover, but the front of Adrian Tinniswood's wonderful The Houses of Guinness (Batsford, £30) does a wonderful job of foreshadowing what lies within. Showing an impending storm over Kenwood House on its thunderous cover, it's as darkly rich and creamy as the eponymous porter, and a perfect match for the tales told. For this is the real-life Irish version of Succession or, more precisely, Netflix’s current historical drama, House of Guinness.

The Houses of Guinness is a compelling story of the family that became the biggest exporter of stout in the world — James Joyce’s ‘foaming ebon ale’. From 1759, at the brewery on James’s Street, Dublin, to 1997, when the firm came to an end, Tinniswood tracks the business through the men who ran it and the houses they bought, built from scratch or remodelled.

Thirteen properties feature, most in Ireland, with England represented by Kenwood House in London, Kelvedon Hall in Essex, Elveden Hall in Suffolk and Biddesden House, Hampshire, plus an ‘interlude’ on churches. The houses are stage sets for the extravagant lifestyles of the Guinnesses and the sumptuous entertainments they held. The dextrous marshalling of such a privileged cast of characters, setting them within their social and cultural milieus and revelling in their extraordinary lives is this author’s forte.

Luttrellstown Castle near Dublin, bought by the Guinness family in the early 20th century, as pictured in The Houses of Guinness.

At St Anne’s, just outside Dublin, Sir Benjamin Lee Guinness and his brother, Arthur, bought the house together in 1835 and extended it to give the property a more castle-like appearance. Arthur spent more time in his town house at St James’s Gate, but Benjamin Lee and his wife, Elizabeth, established themselves as Dublin society’s leading couple, Benjamin Lee becoming Ireland’s first millionaire.

They bought No 80, St Stephen’s Green in Dublin and a shooting lodge in Co Mayo. At St Anne’s, they created incident-packed gardens with a hermitage, several grottos, a ‘Druidic circle’ of basaltic rocks and a Herculaneum villa. It was Benjamin’s son, Sir Arthur, who gave St Stephen’s Green to the nation — the family was noted for its philanthropy — and transformed St Anne’s into a huge Italianate mansion.

Sir Arthur also turned Ashford Castle on the shore of Lough Corrib into one of the great Irish country houses. He and his wife, Olivia, entertained lavishly in their fantasy castle, holding banquets, house parties, balls and shooting weekends.

Ashford Castle is now a hotel. A very, very nice hotel.

One of many highlights in the book is the 1881 costume ball thrown by Lord and Lady Iveagh at No 80, St Stephen’s Green. Edward Cecil Guinness, Benjamin Lee’s son, had inherited the property in 1868 and turned it into a colossal house, dripping with onyx, marble and alabaster. For the ball, the staircases and passageways were filled with ferns and palms; there were ‘Chinese mandarins and cavaliers, matadors and Elizabethans and powdered ladies of the ancien régime’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Adelaide’s dinners were crowded affairs, so diners, having to sit elbow to elbow, would take it in turns to eat. William Orpen’s visit to paint Lord Iveagh’s portrait at Farmleigh was a hoot. He sat in terror in the newfangled, chauffeur driven motor car that had picked him up and had to re-paint the portrait because the consensus was that the chin was too long and the head too big.

In England, Edward Cecil bought Elveden Hall in Suffolk, with its Mughal interiors, as a base for shooting parties, doubling it in size. In 1919, he was created Earl of Iveagh and Viscount Elveden and, in 1924, bought Kenwood, ensuring that it would be made available to the public, either in 10 years or at his death.

The Guinness influence in the interwar years was most keenly felt at Biddesden. Lord Iveagh’s grandson, Bryan Guinness, married to Diana Mitford, moved into the serene Queen Anne house in 1931, where they entertained artists and writers — Evelyn Waugh, Augustus John, Aldous Huxley — built a domed bathing pavilion decorated with mosaics by Boris Anrep and gave safe harbour to John Betjeman after he had been jilted by Penelope Chetwode. Roland Pym was commissioned to paint delightful trompe l’oeils for the blind windows on the east front.

For the 1960s, it was Luggala, Co Wicklow, where, at Tara Browne’s 21st-birthday party, The Lovin’ Spoonful performed and Brian Jones dropped acid for most of the weekend. The book is full of such stories and no better tribute could be given than that by the current Lord Iveagh, who writes in the foreword that this is ‘an entertaining masterpiece’ in which the ‘essential character of the Guinness family spirit prevails’.

The Houses of Guinness is out now (Batsford, £30).

Timothy Mowl is an architectural historian and writer who has worked as an inspector of historic buildings for English Heritage, an architectural consultant, journalist, lecturer and writer on architecture, conservation, historic landscapes and gardens. He spent many years working at the University of Bristol, teaching architectural history and garden and landscape history, is an honorary professor at the Royal Agricultural University, and is the author of 14 books.