Who won the rivalry between Turner and Constable? It was us, the public

A forthcoming exhibition at Tate Britain that revives the rivalry between these two 19th century painters sheds new light on their relationship.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was his chance to be bold and John Constable seized it. In the spring of 1831, the Suffolk artist, elected a fellow of the Royal Academy two years earlier, was on the hanging committee for the annual exhibition — and he placed his Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows squarely between two of J. M. W. Turner’s golden paintings, Caligula’s Palace and Bridge and Vision of Medea. The arrangement caused a stir, with the press calling it ‘a clash of fire and water’, one painter ‘all heat’, the other ‘humidity’.

Turner and Constable had been compared since at least 1819, but, says Amy Concannon, Manton senior curator of Historic British Art at Tate, it took until 1831 for the two to be pitted as rival powers in landscape art. Until then, the competition had been rather one-sided, with the less celebrated Constable at once remarking, ‘Did you ever see a Turner and not wish to possess it?’ and making snippy comments about ‘he who would be Lord of it all’.

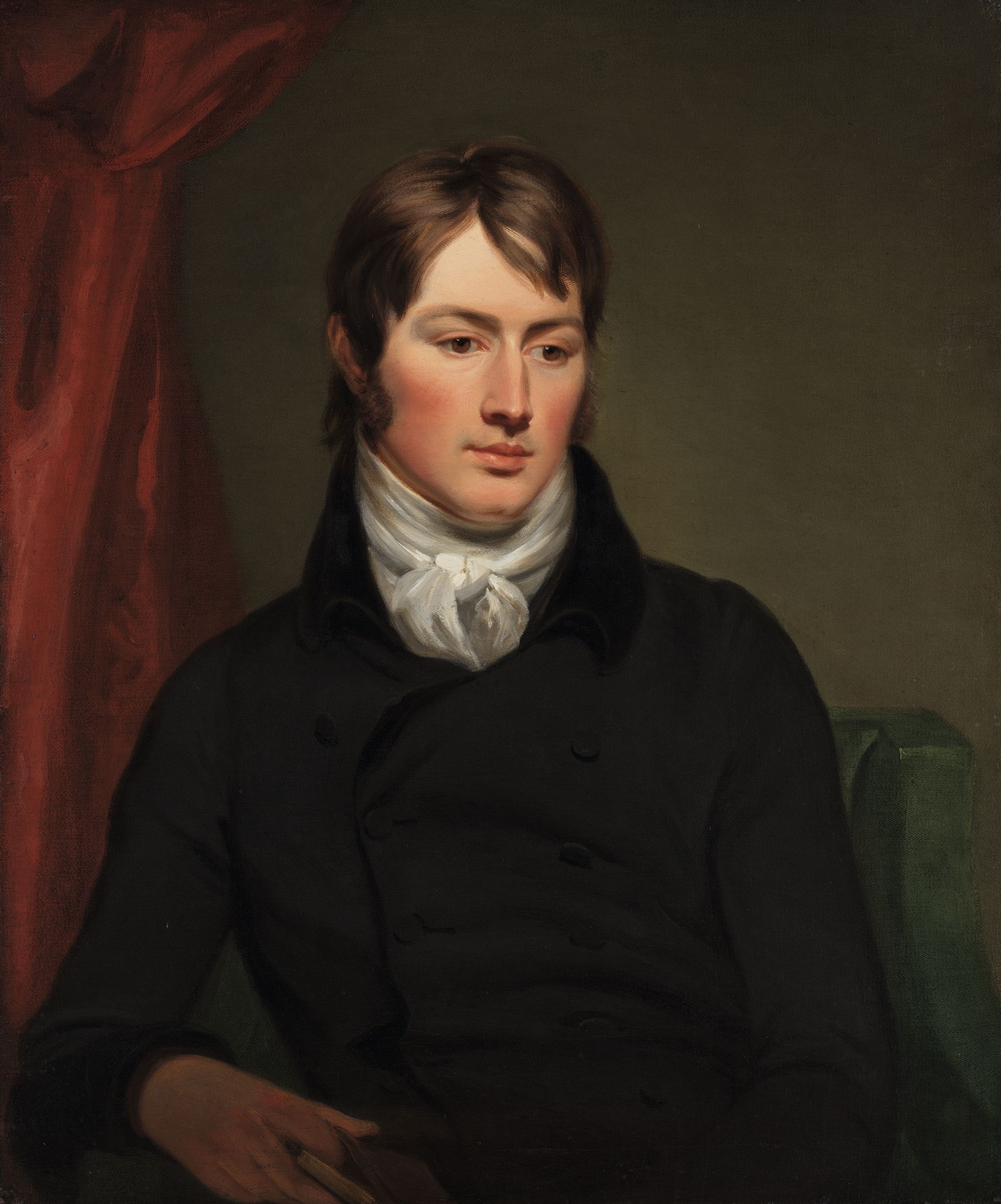

Constable, painted by Ramsay Richard Reinagle

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery

Self portait by Turner

Image credit: Tate

The ‘Lord’ in question probably didn’t give as much thought to his would-be contender — until Constable shunted one of his works to the side to claim the centre spot for himself. When the two artists met one evening, soon after the exhibition had opened, Turner went down upon the younger painter ‘like a sledgehammer’, according to his biographer, Walter Thornbury. A year later, he would put the red buoy on his Helvoetsluys seascape to outshine Constable’s The Opening of Waterloo Bridge, prompting the latter to say: ‘He has been here and fired a gun.’

Nearly two centuries later, Dr Concannon is reviving that rivalry in a forthcoming exhibition, ‘Turner and Constable’, which she has curated for Tate Britain. Intended to celebrate the bicentenary of both artists’ births — Turner’s fell this year; Constable’s is in 2026 — it is a battle of artistic Titans, where some of the hanging had been conceived to suggest ‘what the press saw in 1831’.

Curating the show was itself a titanic effort, with Dr Concannon determined not only to ‘do both artists proud’, but also display rare treats that have not been seen in this country since at least the 1970s — such as Turner’s The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 16 October 1834 — and highlight unexpected facets of their work. As an example, she mentions Constable as a painter of cityscapes: London, Salisbury and Brighton. For all that the Suffolk artist said he ‘should paint [his] own places best’, she finds that ‘he was really at his boldest when out of his comfort zone: it was his painting of London that rattled Turner enough to put that red blob on his seascape’.

The Water: Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows by Constable

The exhibition sets out to challenge the way in which the two artists have long been typecast, Constable as the traditional artist, Turner as ‘the maverick, the really experimental magician’, whose subject matter and technique both point to the future. In fact, argues Dr Concannon, ‘in terms of technique, Constable was probably braver earlier’. At the turn of the 19th century, when paintings were expected to look smooth and polished, with no visible brushstrokes, Turner adhered to the canon; Constable didn’t. ‘He wanted to keep his paint surfaces reflective of the liveliness, freshness and atmosphere in the countryside, so they have that sense of texture, of the landscape moving, the foliage moving. He preferred to keep his brushstrokes quite visible and that was very bold.’

Constable, whose sketching chair will be on display at the exhibition, was also more of a plein-air artist than Turner: ‘He was so wedded to the idea of everything about his work being authentic, he became almost superstitious that he couldn’t make a painting if he hadn’t made at least a sketch of the scene outdoors.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'It’s really impossible for me to choose. There are works by both of them I truly love. Most often, Turner has that initial ‘wow’ factor. However, [with] Constable, you can stand and look at the marks and get lost in his paint surface'

It was London that weaned him off that habit, but not before he had accumulated enough sketches to sustain him for the rest of his career. ‘When you think about how difficult that would have been,’ muses Dr Concannon, noting he would have had to lug pigs’ bladders filled with the oil paints he had previously mixed, as well as dealing with wind, rain, insects and nosy passers-by, ‘you have a new level of respect for Constable’.

She contends that, even in terms of subject matter, both artists were equally modern, reflecting the fast-changing world in which they lived. Turner may have painted steamboats and trains, but the Constable we now see as nostalgic instead captured a transforming landscape: ‘The canal he depicts, that’s one of the earliest industrial innovations in the countryside.’ As Britain’s war against France raged on, he also tapped into national pride. Art, notes Dr Concannon, was used to drum up patriotism: ‘Artists played into a self-congratulatory [message]: “Isn’t our landscape wonderful?” That’s effectively what Constable’s paintings are saying.’

Ask her which she prefers of the two men and she is stumped. ‘It’s really impossible for me to choose. There are works by both of them I truly love. Most often, Turner has that initial ‘wow’ factor. However, [with] Constable, you can stand and look at the marks and get lost in his paint surface. They both have something very different to offer.’

The fire: Turner's Caligula's Palace and Bridge.

Where Turner definitely excelled over Constable was in enterprising spirit. The latter made far fewer sales in his lifetime: ‘If something was a success, it was by happenstance: someone liked what he was doing.’ Turner, on the other hand, knew how to please his patrons: ‘I’m sure [he] really loved to paint Venice, but Venice was also a really marketable subject matter.’ Perhaps this contrast stemmed from their origins. Constable came from a more affluent family, but one with ‘quite narrow middle-class expectations’ that initially held him back from an artistic career. Turner not only had the encouragement of his father — and was gaining recognition for his work when Constable had barely started art school — but he lived in Covent Garden among people who had to be resourceful to make ends meet. He believed in himself and in the market, where Constable has a certain reticence in ‘getting his hands dirty’.

Yet, at a human level, Constable is perhaps the more relatable: ‘He always struggled with his confidence. He worried if things were good enough, whether his paintings were finished. There was one point when he was between houses and he worried that, because his studio was in London, but his family was in Hampstead, he could neither work very well, nor parent his children very well.’ In this, he was already a man of our times.

‘Turner and Constable’ is at Tate Britain, London SW1, from November 27–April 26, 2026

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.