Forget Bond, the understated George Smiley is fiction's greatest spy

As a new exhibition in Oxford charts John le Carré’s legacy, Emma Hughes takes a closer look at his most enduring creation, George Smiley.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sixty years ago this month, at the end of 1965, Bond fever was sweeping Britain. Thunderball was breaking box-office records and The Man With The Golden Gun, Ian Fleming’s final novel, was a runaway bestseller — but, quietly, almost unnoticed, a very different sort of spy was about to make his cinema debut.

George Smiley is easy to miss in Martin Ritt’s adaptation of John le Carré’s 1963 novel The Spy Who Came In From The Cold. Played by Rupert Davies, he cuts a rotund and unthreatening figure, easily outshone by Richard Burton’s MI6 agent Alec Leamas. However, in the six decades since then, he has somehow managed to notch up almost as many outings as James Bond himself. He is currently in Oxford, integral to ‘John le Carré: Tradecraft’, a new exhibition at the Bodleian Libraries which tells his origin story. It’s superbly done, although Smiley, one of fiction’s most self-effacing men, would surely wince at the thought of display cases being devoted to him.

For Nick Harkaway, le Carré’s youngest son, he has always been like family. ‘My dad would write sections of the books and then read them out loud to my mum,’ he remembers. ‘When I was acquiring language, I was getting 90 minutes of Smiley a day, not only his dialogue, but his world as it evolved.’ Later, he would fall asleep listening to cassette tapes of the novels, drifting off as Smiley unravelled another knotty mystery. ‘Although he belongs to the world of espionage, the books work like detective stories — my dad was a huge Sherlock Holmes fan.’

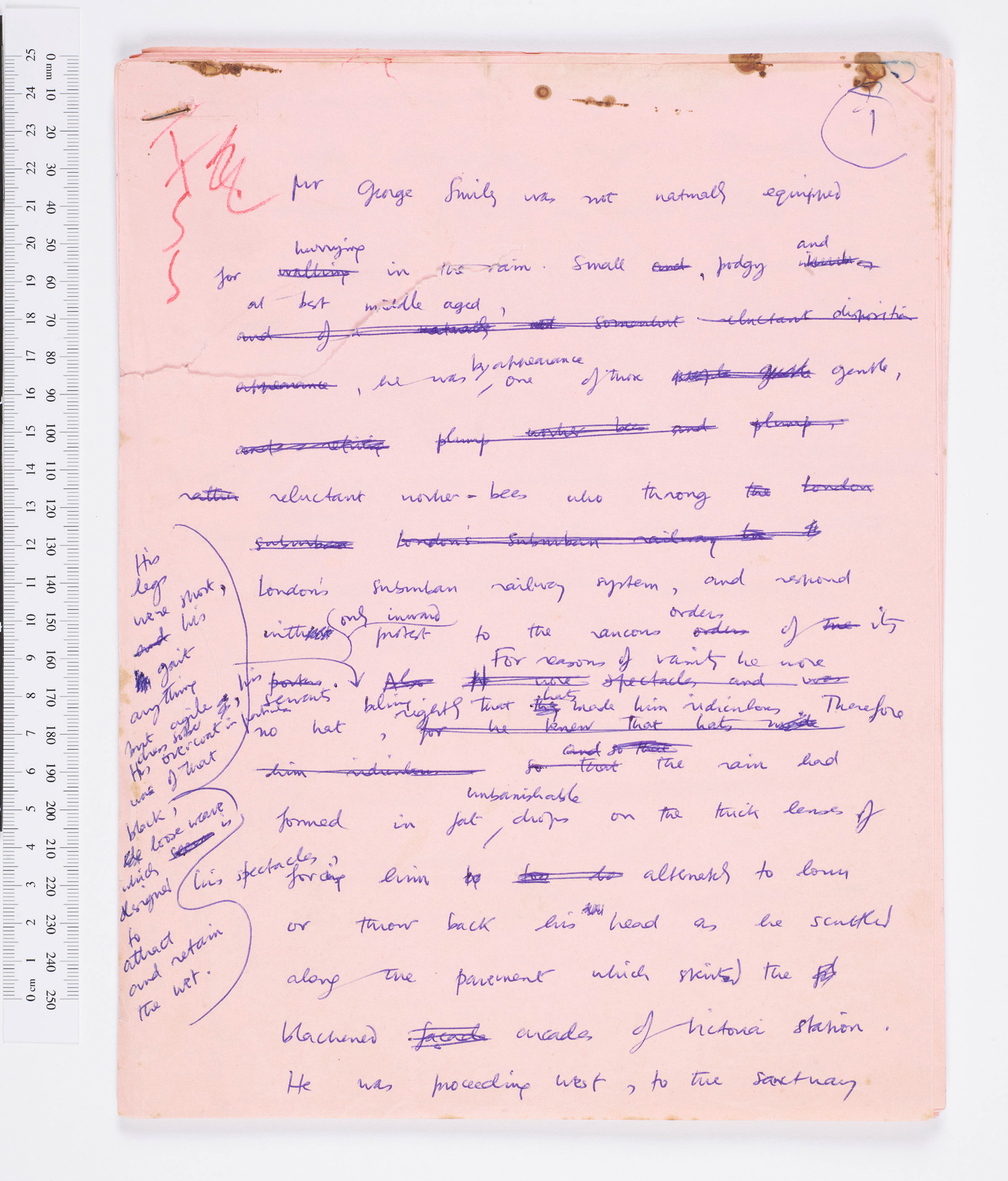

A handwritten draft for Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy in which George Smiley is described as 'small, podgy and at best middle-aged'.

Smiley was born between 1906 or 1916 (the date changes in the novels, stranding him in permanent middle age), but his birth as a character came in the late 1950s when le Carré, then an intelligence officer named David Cornwell, turned his hand to fiction during his commute from Buckinghamshire to MI5 in London. It was the height of the Cold War and the spy-heroes of the 1940s were having to get to grips with a less swashbuckling milieu. Amid stewed tea and clacking typewriters, George Smiley emerged as the antithesis of a kiss-kiss, bang-bang 007 figure.

‘Le Carré was quite explicit about the fact that his spy world was directly in opposition to Ian Fleming’s,’ explains Dr Jessica Douthwaite, co-curator of the Bodleian exhibition. ‘He did an interview with Malcolm Muggeridge in 1966 in which he described Bond as an “international gangster” rather than a spy.’

In the books, Smiley is short and tubby, dressed not in a dinner jacket, but a poorly fitting suit. He is an outsider who travels through life ‘without labels in the guard’s van of the social express’. After being recruited at Oxford and a stint undercover in Nazi Germany, he forms an unlikely attachment to his boss’s beautiful secretary, Lady Ann Sercomb. There, any suggestion of glamour ends: the match is roundly mocked and Ann betrays her ‘breathtakingly ordinary’ husband continually, starting with a racing driver. Her infidelities are so public that innuendo follows Smiley wherever he goes, at least until the events of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy turn him — reluctantly — into the most influential man in British intelligence.

Smiley’s consolation is his desk job at a fictionalised MI6’s grubby headquarters, the Circus. His work feels rather cloistered when he is introduced in 1961’s Call For The Dead, but it becomes increasingly high-stakes: over the course of eight more novels he is dismissed and reinstated, wrangles with Soviet spymaster Karla and saves the day repeatedly, although always at a cost.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'Thus George marches on, his dream of a quiet life continually thwarted by a country that needs him'

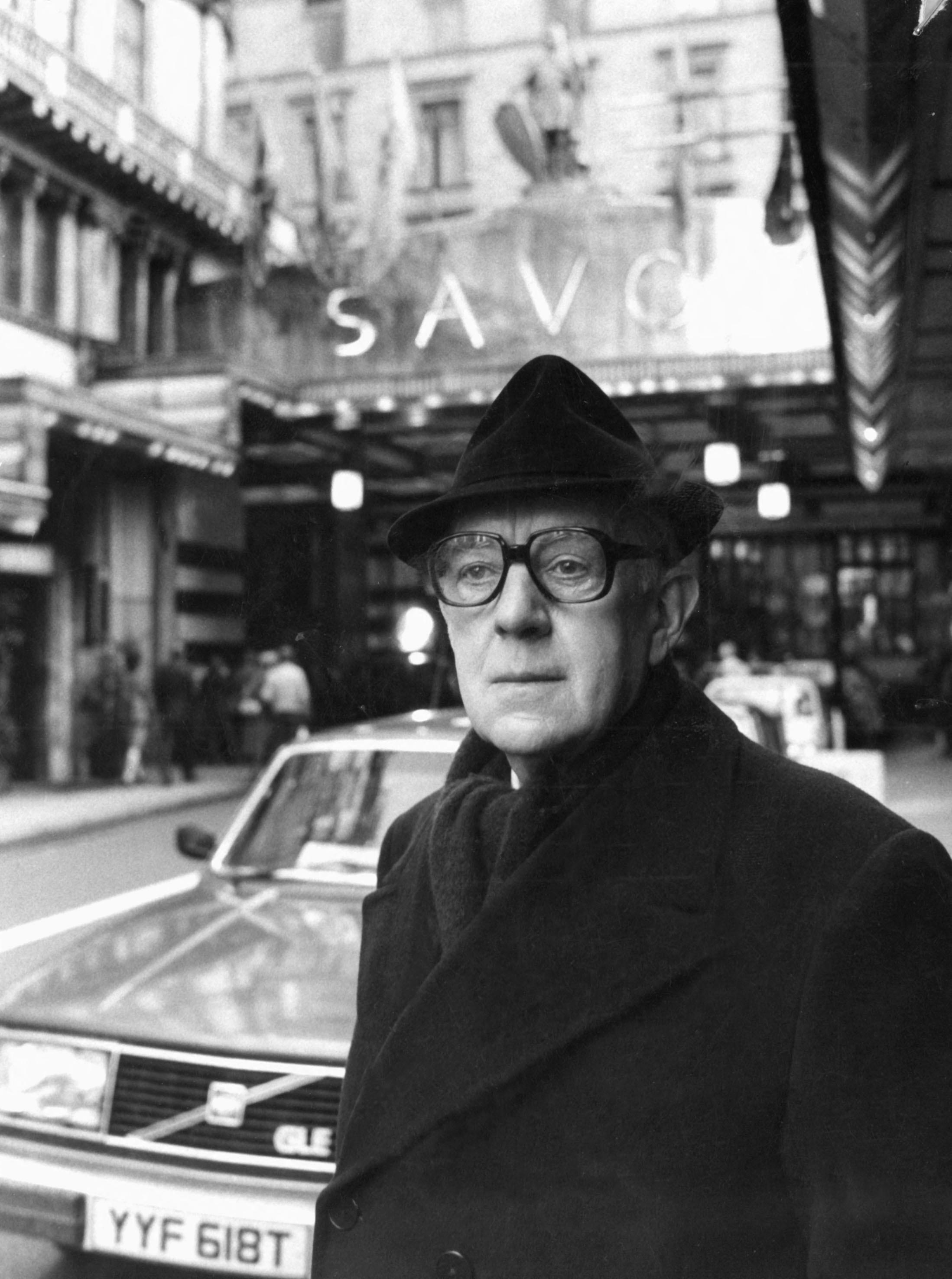

What really propelled him into the limelight was the BBC’s 1979 adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, which drew eight million viewers per episode and created the bowler-hatted Smiley of myth. Tall and imposing, Sir Alec Guinness was physically unlike the ‘bullfrog in a sou’wester’ of the novels and, according to a letter in the Bodleian, he worried he wasn’t right for the part, even suggesting later that Arthur Lowe (Capt Mainwaring in Dad’s Army) replace him. It was le Carré who persuaded him. ‘He wanted to meet a spy, so he and my father went for lunch with Sir Maurice Oldfield [the retired head of MI6],’ Nick recalls. Sir Alec noticed he swung his umbrella ‘in a Charlie Chaplin sort of way’; the detail made it into the show.

Part of the series’ genius lay in its resistance to pyrotechnics and quipping. Much of the action is conveyed by no more than the twitch of an eyebrow and Sir Alec’s Smiley is a Prufrockian figure, cautious and meticulous, entirely without spy-game glitz. ‘It’s a far more realistic characterisation than the idea of someone endlessly glamorous and urbane,’ says novelist Charlotte Philby, whose own thrillers are full of ‘outsiders in a world that doesn’t belong to them’. Le Carré’s shadowy universe has long overlapped with hers: one of his books sat on a shelf in her parents’ house alongside all the volumes on her grandfather, the Cambridge spy and defector Kim Philby.

Smiley’s growing fame was a double-edged sword: le Carré himself found ‘his’ version increasingly difficult to write. ‘For a while the only voice he could hear was Guinness’s,’ says Nick. Smiley, however, was confirmed as a national treasure by being sent up by the Two Ronnies in 1985 and two late-1980s BBC radio adaptations. Denholm Elliott stepped in to play him in 1991’s A Murder of Quality. There are never any exploding pens or car chases: the thrill, as Dr Douthwaite puts it, is in the juxtaposition of ‘Smiley’s idiosyncrasies and insecurities and his extraordinary competence and capability’. Bond is superhuman, impossible to emulate, but we like to believe that we could rise to the occasion as Smiley does.

Alec Guinness as the eponymous spymaster in 1982's Smiley's People

The next person to drag him out of retirement was Swedish director Tomas Alfredson, who remade Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy in noir style in 2011. Le Carré breakfasted with Sir Gary Oldman, who borrowed some of his mannerisms for his painfully solitary yet steely Smiley (le Carré subsequently kept a photograph of him in costume on a bookcase). He would later don a much grubbier mackintosh to play a kind of parallel-universe version gone to seed: Jackson Lamb of Slow Horses, star of the ‘Slough House’ novels by Mick Herron, who was gripped by the BBC’s le Carré adaptations as a boy.

Le Carré died in 2020, aged 89, leaving instructions that his family should try to continue his legacy. Nick, by then a successful novelist, was persuaded by his brother to write a Smiley novel, which he set in 1963, between The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. As soon as he sat down, he found a familiar figure by his desk. ‘It was as if Smiley was there, waiting patiently, and I was slightly late — if you’re quite prepared, Nicholas, we may begin,’ he writes in the novel’s introduction. He felt, too, the presence of every actor who had taken on the role. ‘Each of them did him slightly differently, but each subsequent to the first with a homage to each other. All those inheritances were mine to draw on. His voice is melancholic, it’s contemplative, it’s internal, it’s gentle, slightly suffering… It’s ultimately about revelation and in some senses faith, whether it’s disappointed or not, in humanity.’

Karla’s Choice was an instant bestseller in 2024; there are hopes for a sequel. Meanwhile, earlier this year it was announced that Matthew Macfadyen will play Smiley in a new series. Thus George marches on, his dream of a quiet life continually thwarted by a country that needs him. He offers us the hope that someone seemingly unremarkable can, as Nick puts it, ‘pick up the pieces of the broken vase, then tell you not only how it was broken, but how to put it back together’ — and, in our age of bombast, there is something very appealing about his understatedness.

‘George, you won,’ declares his friend Peter Guillam at the end of Smiley’s People after Karla has been vanquished. ‘Did I?’ says Smiley, with the gentle bemusement of a man who, against stiff competition, has just been awarded the prize for best-kept garden at the village fête. ‘Yes. Yes, well I suppose I did.’

‘John le Carré: Tradecraft’ is at the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, until April 6, 2026

Emma Hughes lives in London and has spent the past 15 years writing for publications including the Guardian, the Telegraph, the Evening Standard, Waitrose Food, British Vogue and Condé Nast Traveller. Currently Country Life's Acting Assistant Features Editor and its London Life restaurant columnist, if she isn't tapping away at a keyboard she's probably taking something out of the oven (or eating it).