How the spirit of Andy Warhol lives on through Christmas

Andy Warhol found Christmas a tricky time, yet threw himself into the festivities and, when he decided to illustrate his series on American myths, he had no doubt he should include the jolly old man in the bright red suit.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

'Christmas,’ quipped Andy Warhol, ‘is when you have to go to the bank and get crisp money to put in envelopes from the stationery store for tips. After you tip the doorman, he goes on sick leave or quits and the new one isn’t impressed.’ A bit ‘Bah, humbug!’, but then the American pop artist would have had every reason to resent the holidays.

Growing up in a poor family of Carpatho-Rusyn origins, his Christmas had not only been on a different day from most Americans — the Warholas, who practised Byzantine-rite Catholicism, celebrated on January 6 — but it had also been meagre: ‘When I was a child, I never had a fantasy about having a maid, what I had a fantasy about having was candy,’ he wrote in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. Then, as an adult, the distance — not only physical — that separated him from his relatives made Christmas a tricky time, especially after he sent his mother, who had suffered a stroke, back to his native Pittsburgh in 1971: the sense of guilt kept eating him up every December for more than a decade after she had died.

Even when he had gathered a surrogate family of his own — a vast entourage of friends, acquaintances and hangers-on — the season to be merry often turned out to be anything but. In 1950, at a Christmas Eve party in which he had perhaps entertained hopes of spending time with the poet Ralph Ward, of whom he was enamoured, their friend George Klauber got badly hurt, after which both an ambulance and the police arrived at the scene: ‘Andy was very upset and left immediately, but waited downstairs for Ralph, thinking that he and Ralph could go off together,’ recalled Klauber. ‘Unfortunately for Andy, Ralph came with me to the hospital.’

'Valerie Solanas, a woman he had helped and who, in turn, had attempted to murder him, called his studio just before Christmas, threatening to try again'

In 1968, Valerie Solanas, a woman he had helped and who, in turn, had attempted to murder him, called his studio just before Christmas, threatening to try again, unless Warhol dropped the criminal charges against her and paid her $20,000. On December 21, 1980, his then boyfriend, Jed Johnson, put an end to what had perhaps been the most important romantic relationship in Warhol’s life.

Yet, despite all this, despite that doorman quip in his book and despite the money worries that seemed to grip him every Christmastide, the artist never really surrendered to his inner Scrooge. Even following his breakup with Johnson in 1980 — when he told his ‘human diary’, Pat Hackett, to whom he dictated his daily memoirs, that he’d ‘been having the most un-Christmas spirit of [his] life’ — he tried desperately to get back into the festive mood.

Christmas had given Warhol one of his early professional breaks: in his illustrator days, he designed whimsical cards for the Museum of Modern Art, Bergdorf Goodman and Tiffany: a star formed from colourful doves or a golden tree made of mermaids and cupids, crowns and cats. More than that, however, the mix of Christianity, tradition, partying and rampant consumer culture — as Pop as Pop could ever get — made Christmas the perfect holiday for a man who was as devout to religion as he was to carousing.

A painting of a ticket to Studio 54, with an inscription to Truman Capote on the reverse.

He threw himself into the festivities with fervour and bought presents generously, almost with abandon: ‘He would spend weeks Christmas shopping for his vast number of friends, often up to half the day every day during the last couple of weeks, and arrive at [his studio, known as] The Factory laden down with treasures…’ wrote Victor Bockris in Warhol. ‘All this joie de vivre climaxed with the yearly Factory Christmas party at which all his friends would gather and even the lowliest member of staff would receive a gift.’ Caviar and Champagne were on tap, everyone was given at least a simple wristwatch and close friends would get legendary presents such as, in 1978, the silkscreen paintings of the complimentary drink tickets at New York nightclub Studio 54. That same year, he also starred on the cover of High Times magazine as a dog-carrying Santa to (a very drunk) Truman Capote’s little elf boy.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

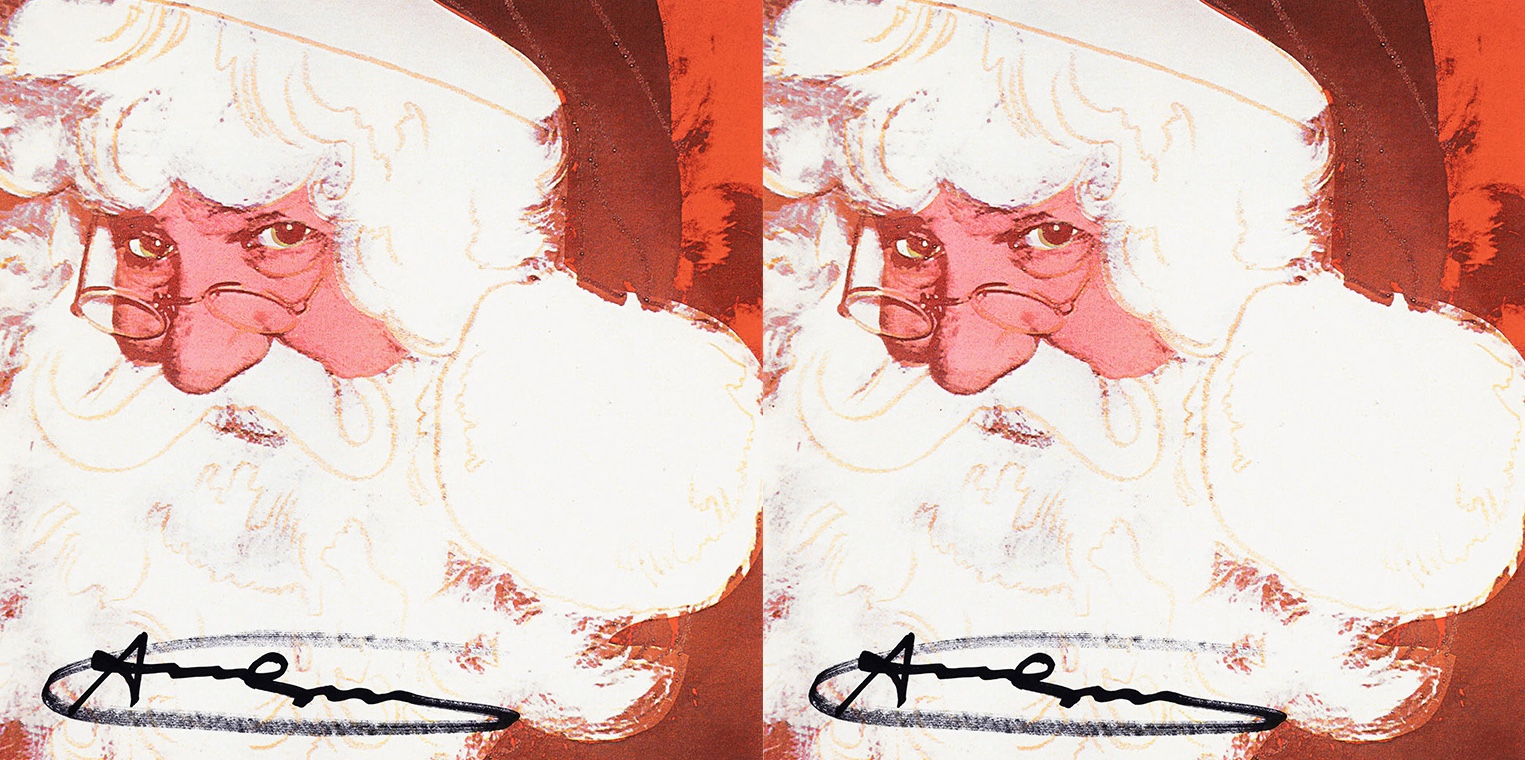

It’s hardly surprising, then, that when he began work on his 1981 series on American myths, Warhol included Santa Claus, together with Superman, Mickey Mouse and Uncle Sam. He took Polaroid pictures of actor John Viggiano dressed as St Nick — the department-store variety — with his round glasses low on the nose, lush fake white beard, a hint of a cheeky smile and an amused twinkle in his eye. From the photographs, Warhol made silkscreen prints infused with nostalgia, but also acute in their reflection on the popular culture of the late 20th century. The old man in red was the ultimate celebrity, the emblem of materialism and consumption. Yet, for Warhol it was also perhaps a link to the religion of his childhood, as St Nicholas, the ‘wonderworker’, is the patron of the Byzantine-rite church.

Christmas Tree by Andy Warhol, of about 1957.

The artist doubled down on the Christmas theme, if more subtly, in 1982, with his ‘Poinsettia’ series. That year, like the one that preceded it and the two that followed, he spent the holidays in Colorado with his then love interest, Jon Gould, but all was not well: despite having given everyone ‘framed underwear’ as presents, he noted in 1982 that he had ‘spent a miserable Christmas’. Eventually, he and Gould broke up, yet Warhol clung on to what he could of holiday magic: on December 22, 1985, he bought himself ‘another Santa Claus sculpture’, then ‘took a gang to Nippon for Christmas Eve dinner’ and tried to fend off his solitude by feeding people at the soup kitchen run by the Church of the Heavenly Rest.

He was struck by the gulf between the ‘beautiful, perfect people’ that populated his world and those ‘with bad teeth and everything’ he nourished on the day. ‘It’s such a different world,’ he told Ms Hackett, but volunteered again the following year. Shortly afterwards, on February 22, 1987, he died. Yet, his Christmas spirit lives on in his prints, in the Deck the Walls art sale and party held every December at the New York Academy of Art he founded — and in the soup kitchens across the world that feed those in need on Christmas Day.

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.