Eccentric, awe-inspiring and a home-from-home for literary giants: Why the London Library is an institution like no other

The London Library is celebrating 180 years in St James’s Square.

On the night of February 23, 1944, a series of 500lb German bombs crashed down on St James’s, shattering the windows of the Chapel Royal and ripping a hole in the western corner of St James’s Square. Had you been picking your way across the debris afterwards, you would have witnessed an extraordinary rescue operation: a human chain of British and American servicemen and bespectacled Bloomsbury types scrambling to load books into wheelbarrows.

Having survived nearly two wars unscathed (after an October 1917 bombing raid that ‘produced havoc in Piccadilly… our London Library stands whole,’ Virginia Woolf recorded), No 14’s luck had run out — the tall, narrow building’s north-west wing had suffered a hit that destroyed 16,000 books, with those remaining vulnerable to rain and the Fire Brigade’s hoses. It could easily have been the end had it not been for the members and their friends: when the news broke, they rushed to the scene to help salvage what they could.

Among them was the diarist James Lees-Milne, who read about the bombing in Brooks’s and hurried over. ‘It is a tragic sight,’ he wrote, describing ‘books lying torn and coverless. The dust [was] overwhelming. I looked like a snowman at the end’. He spent an hour perching on a girder ‘over an abyss’ catching books thrown to him; the novelist Rose Macaulay, then in her sixties, is said to have volunteered to be held out of the building by her ankles to help get them down to street level. The rescued volumes were carefully wheeled over to the crypt of the National Gallery, where they stayed for the rest of the war.

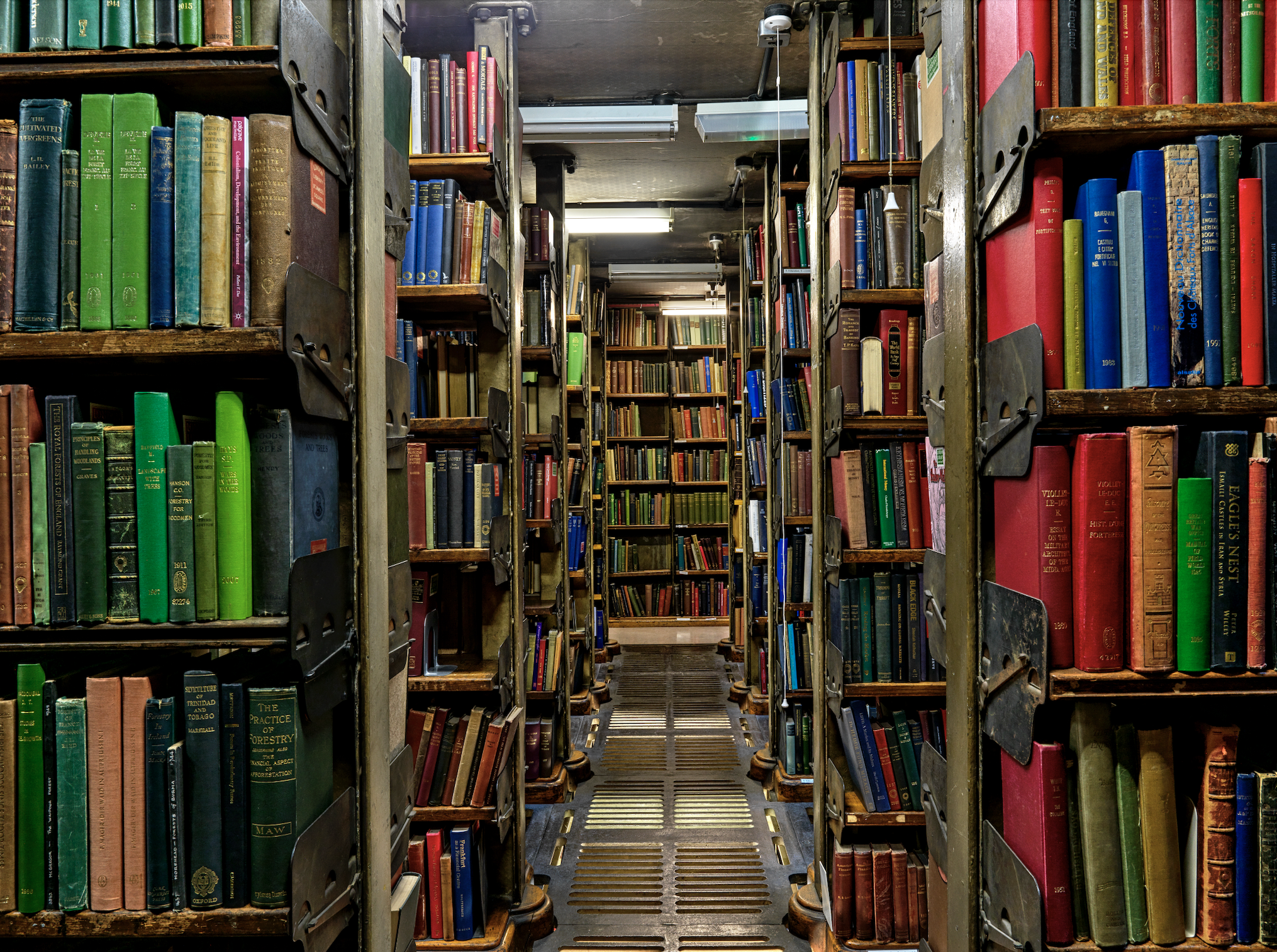

Somehow, this episode isn’t the most colourful footnote in the London Library’s 180-year history in St James’s Square. It is, by any measure, an extraordinary place: visually a cross between White’s and the warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, a ‘midwife, refuge, goldmine and cocoon,’ according to John Julius Norwich in 1978. ‘If I were stopped in the street by one of those opinion pollsters and asked to list three specifically British cultural institutions of which I was proudest, my answer would be unhesitating and categorical… the BBC, the National Trust and the London Library,’ he added.

Bram Stoker researched Dracula in the library and Ian Fleming gave it a cameo in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

As well as being home to a 1611 King James Bible, a Fourth Folio of Shakespeare and a first edition of On the Origin of Species, the London Library’s membership records read like a Who’s Who of British literary history: Alfred, Lord Tennyson, J. M. Barrie, Joseph Conrad, Vita Sackville-West, George Eliot, T. S. Eliot, Evelyn Waugh, Siegfried Sassoon, Stella Gibbons, Nancy Mitford, Daphne du Maurier. Bram Stoker researched Dracula here, Ian Fleming gave it a cameo in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (Bond consults a copy of Burke’s General Armory) and Muriel Spark had its books posted out to her in Italy. More recently, David Nicholls called it one of his favourite places in London, Tom Hanks and Reese Witherspoon posed for photographs outside and Simon Schama declared ‘there is nowhere quite like it’. The chances are that at least one of your favourite novels began its life here: between them, its 7,500 members publish some 700 books every year, plus more than 450 film, television and theatre scripts.

One of them is Victoria Hislop, who joined 15 years ago. ‘When I’m in London, it’s where I go to write; you can leave your domestic life behind and, if you’re a full-time author, it’s nice to have that feeling of packing your satchel and setting off,’ she says. During ‘book crisis periods’ she even comes in on Saturdays, ‘and I do like the late-night opening, being there in the evening in the winter when you know there’s no distractions. It’s an absolute haven’.

‘The minute I saw the place I realised it was ideal,’ agrees William Boyd, who had been hunting for a place to write when he moved from Oxford to London in 1983. ‘At that point, it was something of a time capsule. It’s changed a lot since then, but after all these years as a member it’s a wonderfully reassuring institution. You know there are kindred spirits all around you.’ His books are famous for their globetrotting — the latest, The Predicament, races from Guatemala to West Berlin — and ‘even in the age of Google I have found information in the London Library that the internet couldn’t provide.’ Searching for a guide to the manufacturing of corned beef in Uruguay when writing Any Human Heart, the London Library came up trumps.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

With its Portland-stone façade, Robert Adam fireplace in the study, shelves of obscure bound volumes (many of which can be borrowed for months at a time) and leather arm-chairs bearing the impress of countless naps, the London Library looks, and feels, like a club. However, unlike those around the corner on Pall Mall, it’s one that absolutely anyone can join. ‘It’s very democratic,’ confirms Sir Charles Saumarez Smith, who joined the committee in 1988 as a young man. Back then, the atmosphere was rarified, but, today, it’s much more diverse, thanks to discounted off-peak, remote, overseas and youth memberships. ‘One of the things I really admire is the way it has modernised and attracted new members: I’m struck by how many younger people use it now. My sons go a lot.’ With university libraries becoming ever-more digitised, he feels, London students are increasingly seeking out paper, print and human connection.

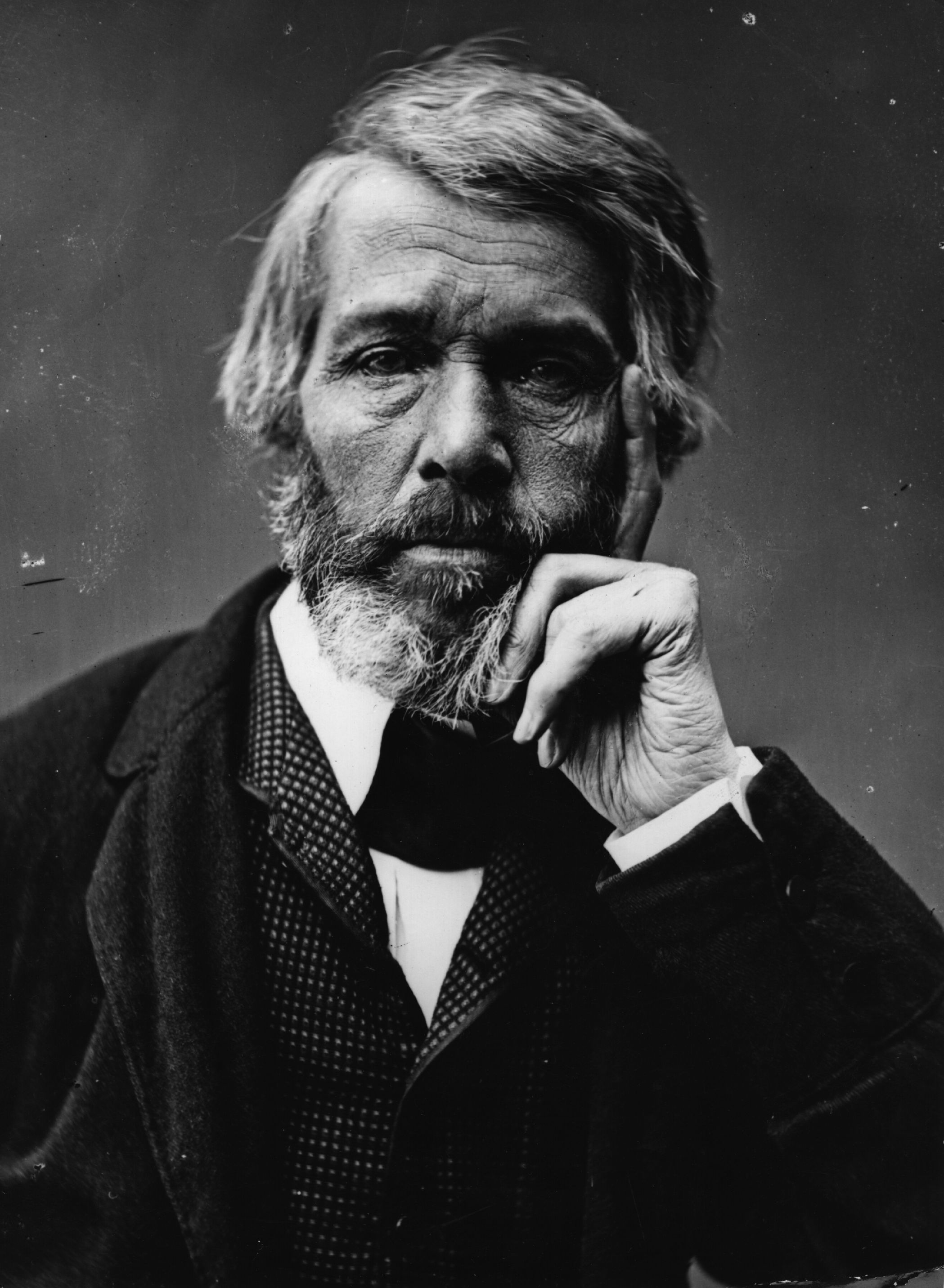

Members have one man to thank for it all: the essayist Thomas Carlyle. In the late 1830s, he became so fed up with the ‘buzz and bustle’ of the British Library’s reading rooms, as well as the fact he couldn’t take any of the books home to Chelsea, that he decided to set up his own. ‘We have no library here from which to borrow books, and we are striving to get one,’ he informed Ralph Waldo on February 8, 1839, before leaning on friends, including Charles Dickens and John Stuart Mill, to drum up support. Five hundred initial subscribers were found and two rooms on Pall Mall were stocked with 3,000 volumes. The London Library opened on May 3, 1841.

Thomas Carlyle

Although the collection was much more limited than it is today — a testy notice from the first librarian reminded members that ‘this Library does not undertake to supply the various Novels of the day’ — before long it had out-grown its digs and a new home had to be found. In 1845, the committee settled on what was then called Beauchamp House in St James’s Square, which had a dilapidated air after years of being let out (the writer A. I. Dasent pooh-poohed it as ‘the worst house in the Square’). The members didn’t seem to mind: within 12 months, there were 746 of them, with Prince Albert serving as the first royal patron (setting a precedent that Edward VII, Georges V and VI, Elizabeth II and The Queen would all follow). The freehold was secured in 1879 for £21,000.

The arrival of gas lighting in 1866, replacing precarious candle-lamps, had enabled the Library to stay open later, but space continued to be a problem. A solution came from America in the late 1890s: a steel-framed extension of ‘stacks’ with metal-grilled floors. It was one of the first such structures in London and took three years to build as part of a complete overhaul of the premises; Sir Leslie Stephen, who, as well as being president (and Virginia Woolf’s father), was a keen mountaineer, could sometimes be seen scaling the scaffolding to keep an eye on things.

Dimly lit, warren-like and prone to clanging spookily, the stacks are straight out of Hitchcock and, in fact, have appeared in more than one fictional mystery: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1925 short story The Adventure of the Illustrious Client has Watson hurrying back to Baker Street ‘with a goodly volume [on Chinese pottery] under my arm’ and A. S. Byatt’s literary whodunnit Possession opens with a chance discovery by a researcher in a book he has requested.

The proprietary classification system is famously eccentric. ‘One of my favourite juxtapositions is Fishing being next to Flagellation,’ says Country Life’s David Profumo, who joined as a student at Kings College. ‘This morning, I also saw Elephants by Electroplating.’ All 17 miles of shelves (the length of the Circle line) are open for browsing and Kazuo Ishiguro was inspired to write The Remains of the Day by a copy of Harold Laski’s The Danger of Being a Gentleman he stumbled across in the stacks. Not everyone, however, finds the ease of access entirely helpful: the Booker-longlisted novelist and New Yorker gardening correspondent Charlotte Mendelson jokingly describes the London Library as ‘a terrible place to write because it’s so interesting. My current novel has taken a while to get off the ground and it’s definitely the Library’s fault — so much vital research to do on fruit, or weaponry or medieval Northumberland’.

A post shared by The London Library (@thelondonlibrary)

A photo posted by on

Having survived being bombed, the Library faced bankruptcy in the late 1950s. Churchill rode to its defence in The Times and, once again, writers came to the rescue by donating lots for a fundraising auction at Christie’s in 1960; they included Ian Fleming’s dressing gown and slippers and the original manuscript of A Passage To India. The financial and practical challenges of maintaining such an idiosyncratic building in the heart of a city remain — and, of course, every few years, another half mile or so of books joins the collection. A sympathetic programme of improvement work is currently under way, following 2014 RIBA Award-winning renovations by architects Haworth Tompkins, which, among other things, created a new reading room in the light-well, improved accessibility and made thoughtful use of brass-meshed shelving and glass.

Throughout it all, the Library’s presidents have raised both its public profile and much-needed funds. In 2022 Helena Bonham-Carter succeeded Sir Tim Rice, becoming the first woman to hold the title. She joined not long after starring in A Room With A View, following in the footsteps of her great-great-uncle John Bonham-Carter, a Liberal MP and early member. ‘The past is so tangibly present that it’s almost like you’re walking through a time warp,’ she said when she was appointed. She has immersed herself in the life of the library, throwing a suitably literary biannual party in the Reading Room: the most recent one saw Sebastian Faulks and The Crown’s Tobias Menzies performing a section of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Addressing members in 1952, T. S. Eliot warned that ‘whatever social changes come about, the disappearance of the London Library would be a disaster to civilisation’. It would also be a personal tragedy to all the writers, students and book-loving Londoners who file through the doors at 9.30am into the Issue Hall, perhaps hanging a hat up on the venerable stand before making their way to a desk to sit among the benevolent ghosts who also wrestled with the blank page in their time. It’s easy to see why so many members were prepared to risk life and limb in 1944 — there is nowhere else quite so full of illustrious stories, and yet so welcoming, in the capital. Back to Julius Norwich: ‘I know of no more wholly agreeable environment anywhere,’ was his verdict, ‘and in a London without the London Library I should not wish to live.’

Visit the London Library's website for more information.

Emma Hughes lives in London and has spent the past 15 years writing for publications including the Guardian, the Telegraph, the Evening Standard, Waitrose Food, British Vogue and Condé Nast Traveller. Currently Country Life's Acting Assistant Features Editor and its London Life restaurant columnist, if she isn't tapping away at a keyboard she's probably taking something out of the oven (or eating it).