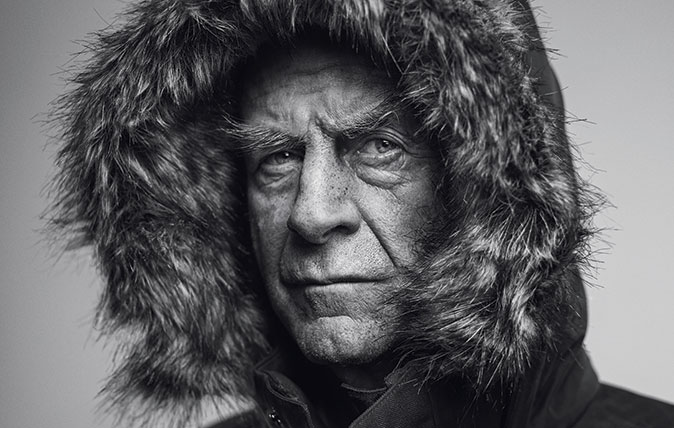

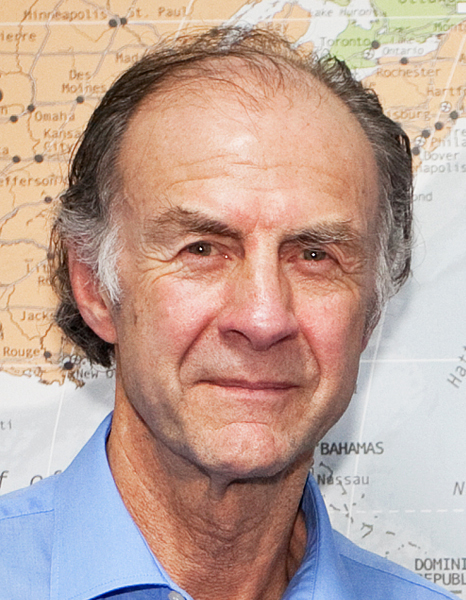

Ranulph Fiennes: 'Commuting up and down the motorway is more dangerous than a trip to the Arctic'

Explorer, adventurer and national treasure, Sir Ranulph Fiennes has travelled to the ends of the earth and raised millions for charity in the process – all while remaining a true gentleman. He spoke to Jonathan Self.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

‘How do you do, Sir Ranulph?’ I say, shaking the proffered hand (which, incidentally, is XXL, rather like everything else to do with the great explorer).

‘Please, call me Ran. Everyone does,’ he booms back, springing out of one of the Royal Geographical Society’s deepest armchairs with the energy of a man half his age (he’s 73). ‘I must apologise, but I am afraid you’ll have to shout. I was learning to dive yesterday and I seem to have perforated my eardrum.’

After we’re seated and refreshments ordered, Sir Ranulph smiles encouragingly. ‘I thought I would begin by asking you about your life as an explorer and then, perhaps, move on to other, more personal subjects,’ I venture.

This is met with a loud harrumph. ‘I’m dreadfully sorry. You know how it is, but I really would prefer not to say anything about my wife, Louise, or our daughter.’

"Brave, fearless, kindly, trusting, larger than life, indiscreet, irreverent, passionately concerned with justice, perfectly mannered and somewhat contradictory"

I hasten to assure him that it isn’t my intention to pry, but Sir Ranulph frequently returns unprompted to the subject of his wife and daughter, providing me with the sort of domestic details that would set a tabloid journalist’s heart racing.

He also tells me about a private meeting with The Prince of Wales, during which the latter, overcome by jetlag, fell sound asleep; why he refers to a certain Norwegian explorer as Ragnar Foreskin; what he would like to do to Roland Huntford, whose book debunking Scott of the Antarctic is clearly still infuriating Sir Ranulph nearly four decades after it was published; and how, at Eton, despite suffering from vertigo, he would climb church spires at night and leave lavatory seats atop their weathervanes.

There, in a nutshell, you have the man: brave, fearless, kindly, trusting, larger than life, indiscreet, irreverent, passionately concerned with justice, perfectly mannered and somewhat contradictory.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Millions of words have been written about him and his exploits, many of them, in fairness, as he’s the author of 20-plus books, by himself. He describes himself as a travel writer on official forms. ‘I hate it when I’m referred to as an adventurer, because it makes me sound like a libertine. I prefer expedition organiser.’

He organised his first expedition at the age of 12, taking his 17-year-old sister, Gill, on a cross-country canoeing trip; it started on the River Lod, which ran close to their Sussex house, and went via the Rother and Arun to the sea, where their mother collected them in her Morris Minor.

He entertained no thoughts of becoming an explorer, but planned to follow in his father’s footsteps into the army. Lt Col Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes commanded the Royal Scots Greys and was killed by a mine in Italy in 1943, four months before his son was born.

By his own account, young Ranulph must have been a handful. He was often beaten by his schoolmaster with, he says, complete justification and, when he was six, he held up the cook with his late father’s service pistol and demanded extra cake. His mother fixed a notice above his bed reading ‘Never, never let your gun/Pointed be at anyone’ and then caned him.

One could describe Sir Ranulph’s teens and early twenties as a series of authority-defying exploits, from breaking into a girl’s boarding school with fireworks and smoke bombs to attempting to blow up a dam that desecrated a beautiful piece of countryside, but this would be misleading.

For every tale he tells about his misdemeanours – he’s a superb raconteur, skilled at making you feel that you’re the first to hear each story – there are several others about close friends, family and, most often, his childhood sweetheart, Virginia Pepper. He met Ginny when she was just nine and their marriage, in 1970, seems to have had a calming effect. Instead of raising hell, he began to raise money for scientific and record-breaking expeditions.

It is with good reason that Guinness World Records lists Sir Ranulph as the World’s Greatest Living Explorer. His first noteworthy achievement was leading the Jostedalsbreen Glacier Expedition in 1967 and, since then, barely a year has passed without his making an unsupported bid for the North Pole or running seven marathons in seven days on seven continents or climbing Everest or crossing the Antarctic plateau during the polar winter.

All this was achieved with the unflagging support of Ginny, who became the first woman to receive the Polar Medal and to whom he was clearly devoted. She was, Sir Ranulph said, the best base leader in the world and when he describes her death from cancer in 2004, I find my eyes tearing up.

Asked which expedition he is proudest of, Sir Ranulph hesitates before deciding it was the discovery of the lost city of Ubar, after several attempts, in 1991. Asked which was the most gruelling, he says all of them seem indescribably difficult at the time, but, on reflection, the most gruelling part of any expedition is raising the money.

And how about the time he amputated his frostbitten fingers with a hacksaw? It seemed a good idea at the time, he says. Ginny brought him comforting cups of tea while he was doing it and his only regret was that it made it ‘jolly tricky to tie my black tie and also to hold those fiddly little plastic forks you get at buffets’.

I suggest that he must be very brave. ‘Not really. I just get on with it. Anyway, it’s considerably more dangerous commuting up and down the motorway every day than mounting a properly equipped, fully supported expedition to, say, the Arctic. I know which I would rather do.’

This emboldens me to ask a final question: ‘Why?’

‘Different reasons at different times. I sort of drifted into it, to begin with, because it seemed better than a proper job.

‘Later, I realised its potential for raising money [£18.9 million so far]. Now, it’s just what I do. I can’t ever imagine stopping.’

In a country that is, let’s face it, rather short on heroes at the moment, this is reassuring to hear.

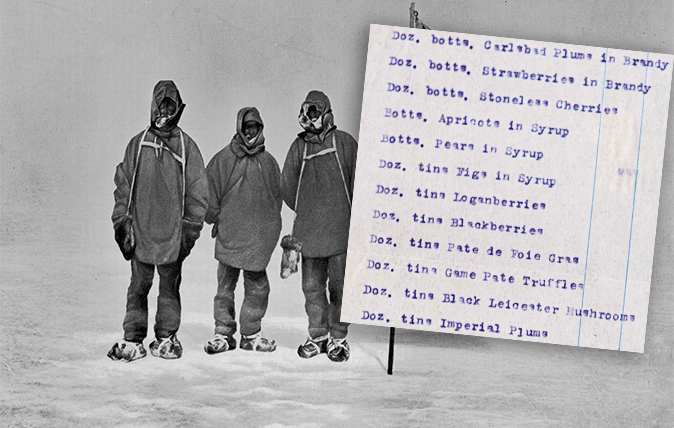

Ernest Shackelton’s arctic shopping list, and other secrets of Britain’s great shops

Harrods, Fortnum & Mason and most of Britain's other great retailers have archivists – and they shared some of their

Credit: Alamy

Gloriously evil: The Top 10 British villains in Hollywood history

Everyone knows Brits make the best on-screen super-villains. Jonathan Self picks out his favourites.

The true story of Eton Mess – and how to make the perfect one

The question, it turns out, isn't 'why' it's called Eton Mess, but whether it's actually called 'Eton Mess' at all...

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.