Needlepoint: The craft of kings, queens and countesses

Far more than a fancy of old ladies, unoccupied hands and evenings are never a problem for enthusiasts of needlepoint. Matthew Dennison takes a look.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

‘I do it avidly, in the evening, watching television,’ the Countess of Hopetoun tells me. ‘At home, although not in the summer, watching the television,’ agrees Romilly, Lady McAlpine. They are discussing the needlepoint that, for both, is a lifelong love, a habit begun in childhood.

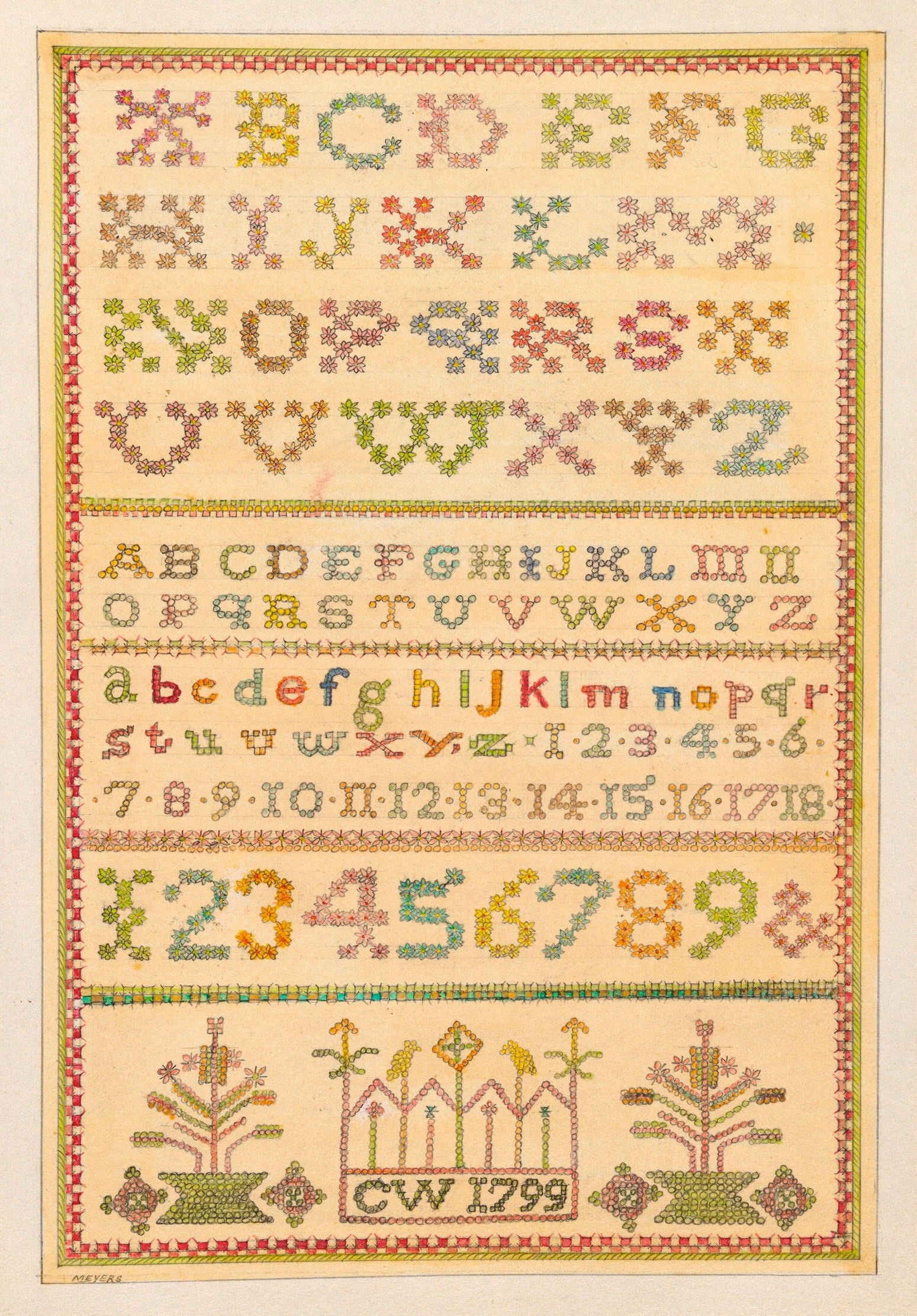

In 1960, the author of the catalogue of an important American collection of historic textiles described all types of needlework as ‘principally domestic art forms [that] reflect more informal aspects of social life than almost any other branch of the decorative arts’. Certainly, this rings true of needlepoint in my life. On winter evenings, my wife, Grainne, establishes herself on the club fender, a Fabled Thread canvas across her knees as the fire warms her fingers and she stitches as we revisit the day’s events. In houses up and down the country, partly thanks to the enforced homeliness of lockdown, needlepoint — a form of embroidery in which coloured yarn is stitched through an open-weave canvas to create an all-over pattern — is once again a favourite pastime among men and women of all ages.

For long-term devotees, this is not a surprise. In South Kensington, Lady Palumbo’s shop La Tapisserie has been providing beautifully designed needlepoint kits to a discerning and loyal clientele since the mid 1980s. Needlepoint, Lady Palumbo explains, is ‘a very social hobby, because it allows you to do other things — talk to friends and family, watch television — at the same time’.

‘I had done needlepoint at school, then I took it up again in my thirties when my daughter Skye was very small,’ remembers Lady McAlpine. ‘Sometimes, I would sit down with a good book in a big cosy armchair next to a lovely fire in our house in Hampshire. But children demand attention: you can’t read a book. I went back to needlepoint. It doesn’t matter if you’re disturbed, you can pick it up and put it down again, even on and off for a couple of years.’

‘Its repetitive quality is meditative,’ suggests Paul Bailie who, since lockdown, has established himself as Britain’s foremost designer of bargello — or flame stitch — needlepoint. Employing the distinctive geometric patterns that have scarcely changed over half a millennium, he creates bespoke cushions, as well as ottoman and chair covers for interior designers and private clients. For Mr Bailie, a former ceramicist and, subsequently, a historic-interiors curator, ‘there’s something wonderful about working with your hands: now, I can’t imagine not doing it any more’. He finds the very simplicity of the needlepoint stitch therapeutic, a verdict echoed by both Lady McAlpine and Lady Palumbo.

Although it took the pandemic and its isolation to turn his thoughts to bargello, Mr Bailie is no stranger to needlework. As a child, he was surrounded by extraordinarily fine embroidered regimental crests worked by his father, a major in the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. Like hunting, baking, a taste for detective fiction, board games or a particular dog breed, needlepoint is frequently a habit that runs in families. In April 1937, a special coronation issue of Needlewoman magazine informed its readers that not only the queen dowager, Queen Mary, but at least two of her children, the new King, George VI, and his sister, the Princess Royal, all enjoyed needlepoint. Both King and Princess, assisted by their respective spouses, were busy working on needlepoint chair covers, it elaborated.

A century ago, at Great Dixter in East Sussex, accomplished embroiderer Daisy Lloyd instructed all five of her sons, as well as her daughter, in needlework techniques. Until his death in 1933, she and her husband, Nathaniel, worked on projects together — sometimes in front of the fire in the Yeoman’s Hall, at other times by the south window in the Great Hall — beginning at opposite ends of the canvas. With her youngest son, Christopher, distinguished gardener and former Country Life contributor, Daisy collaborated on needlepoint covers for a pair of wing armchairs that remain on show to visitors to the house.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

At some point in their lives, all three of Lady Palumbo’s daughters have toyed with their mother’s passion for needlepoint, a taste that she, in turn, absorbed from her German grandmother and a Palestinian godmother, as well as the traditional needlework that surrounded her in her Lebanese childhood. Although Lady Hopetoun acclaims her daughter, Olivia, as ‘much better than me’, her own example surely inspired Lady Olivia’s first sortie into needlepoint slipper-making, a time-consuming endeavour that she has since made her own.

All those consulted echo Lady Palumbo’s assessment of needlepoint as ‘the most rewarding thing’, an aspect of their lives that they could not imagine being without. As Lady Palumbo explained, needlepoint ‘has a big place in my life — I’ve been doing it for as long as my marriage’ — and not only her own home, but those of friends and family members bear witness to her proficiency. Alongside more traditionally patterned pieces, her house in London includes needlepoint designs that she commissioned from leading modern artists, including Patrick Heron, Patrick Caulfield and Elsworth Kelly.

Lady Hopetoun’s taste is more traditional. ‘Most of the stuff I do, my grandmother could have done,’ she comments. It’s possible that her fondness for muted colours and soft, often flower-derived designs has been shaped by her life at Hopetoun, where examples of 17th- and 18th-century needlepoint are visible in both state rooms and the family’s private apartments, including the needlepoint-covered chair in which invariably she sits to stitch in the evening.

There are, of course, faster, more consistent, less exacting means of producing decorative cushions, coverings, slippers or bags, but few that give practitioners more pleasure. Nor do many pastimes place one in a continuum stretching as far back as Elizabethan England, when, in the wake of the Reformation, emerged a new form of secular needlework, dominated by motifs inspired by contemporary herbals and the strapwork designs of renaissance classicism. A single word of warning, courtesy of Lady Palumbo, that may surprise the unwary: ‘This is not only a hobby for old ladies. You have to have good eyes, good fingers — and a good light!’

The wool-spinner still using an 1899 loom and a method handed down for 230 years

Toby Tottle embraces the traditional process of textile production in Mainland Britain's only surviving district woollen mill.

The Dorset button-maker: Easy to learn, cheap to source and fun to create

Born in the heartland of Dorset button-making, Jen Best's yarn shop doubles as a classroom where she passes on her

Credit: Galbraith

A completely self-sustaining house in one of the most remote, idyllic locations imaginable

No. 2 Doune sits on the Knoydart peninsula, known for it’s close knit community, turbulent history and spectacular countryside.