Curious Questions: Who opened the first ever department store?

Forget the mid-19th century institutions of Harrods, Macy's or Bloomingdale's — the oldest department store in the world was founded in London in the 1780s. Martin Fone tells the story of Harding, Howell’s & Co Grand Fashionable Magazine.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Speculation over the future shape of the John Lewis Partnership has once more brought into sharp focus the prospects of the physical retail sector in general and the department store in particular. Despite often occupying prime sites in the centres of cities and towns, their fortunes are in sharp decline, CoStar revealing in August 2021 that with the collapse of BHS, the closure of Debenhams, and the restructuring of other companies, the number of major department stores in the UK had fallen by 83% from 467 in 2016 to seventy-nine. This trend shows no sign of abating.

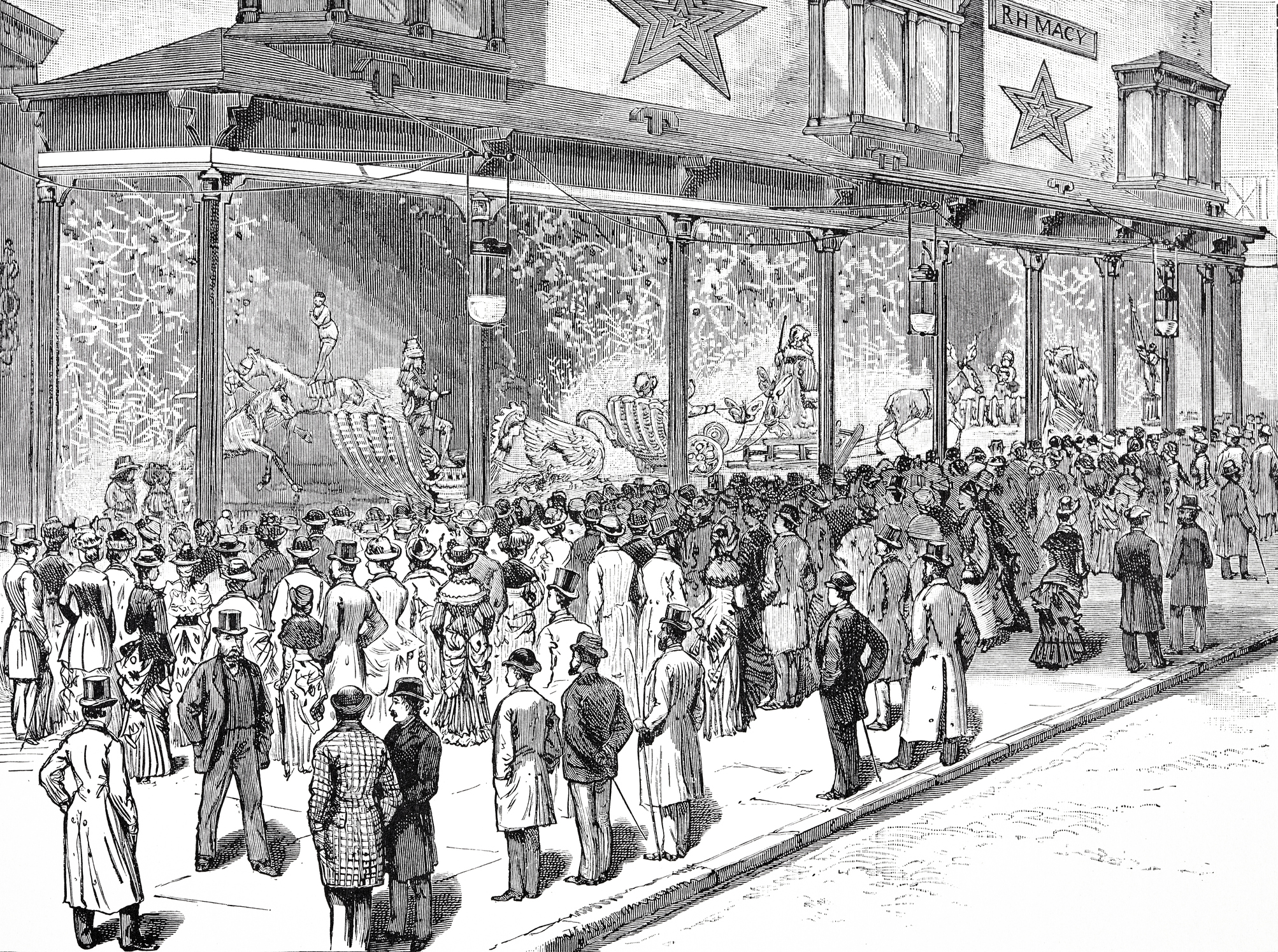

While William Fortnum and Hugh Mason opened their eponymous store at 181, Piccadilly in 1707 and William Clark his shop at 44, Wigmore Street before bringing William Debenham in as a partner in 1813, they were originally a grocery store and a draper’s respectively, only becoming department stores in the 19th century. The same can be said of several other pretenders to the title of the world's first department store: Bennett's in Derby is trading to this day having first opened its doors in 1734, but it was for many years solely an ironmonger. Kendals, in Manchester (now under the House of Fraser name), was founded late in the 18th century, but only became a department store in the 1830s; Harrods life as a department store dates only to the 1850s, as do the oldest examples from New York City, such as Macy's and Bloomingdale's.

Yet while many of those names are still familiar today, the very first department store in the world — and indeed the man who developed the department store concept — is barely remembered. That is in no small measure due to the fact that Anthony Harding's store — Harding, Howell’s & Co Grand Fashionable Magazine — ceased trading over 170 years ago.

Founded in 1789 and located in Schomberg House on Pall Mall, now the site of the RAC Club, it was aimed at the newly affluent middle-class woman, offering them the opportunity to shop for a wide range of goods without the inconvenience of walking chaperoned from one shop to another on the public highway. Designed to be as attractive and enticing as possible, it featured glass chandeliers, tall ceilings from which fabrics were hung and large glass-fronted cases in which merchandise was displayed.

The ground floor was divided by glass partitions into four departments. The first, immediately by the entrance, Ackerman’s Repository of Arts enthused in 1809, was ‘exclusively appropriated to the sale of furs and fans. The second contains haberdashery of every description, silks, muslins, lace, gloves etc. In the third…you meet with a rich assortment of jewellery, ornamental articles in ormolu, French clocks etc, and on the left, with all the different kinds of perfumery necessary for the toilette’.

The fourth department contained millinery, dresses, and textiles, especially chintzes and their accessories. There was ‘no article of female attire or decoration, but what may be here procured in the first style of elegance and fashion’, the article concluded. ‘The present proprietors have spared neither trouble nor expense to ensure the establishment of a superiority over every other in Europe, and to render it perfectly unique in its kind’.

Neither did Harding forget his customers’ creature comforts. After ascending the Schomberg’s magnificent painted staircase to the second floor, the first given over to workrooms employing around forty staff, the shopper found Mr Cosway’s breakfast room. ‘Wines, teas, coffee, and sweetmeats’ were available for consumption and the café offered a pleasant environment in which to compare purchases and catch up on the latest tittle-tattle. A ‘noble apartment [was] used as a shawl room’ and, perhaps most importantly, there were public toilets, a rare convenience for women at the time.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Pall Mall was one of Georgian London’s most fashionable streets and its proximity to St James’ Palace meant that Harding’s store was not short of royal visitors, for whom he would shut the store so that they could browse undisturbed. George III commissioned Harding to design and make the hangings for his bedroom at Kew and to market the cloth produced from the royal flocks of merino sheep that grazed at Windsor.

Harding was never slow to exploit an opportunity. After designing some dress silks for Queen Charlotte, he marketed them to the public as ‘Queen’s silk’, while he ensured that a piece of the chintz produced for the Prince of Wales was pasted to every issue of Ackerman’s Repository of Arts alongside the advertisement for his shop. Samples of the chintz were also sent to every entrant in Debrett’s Peerage to remind them of his royal patronage.

Although at pains to reassure his customers that ‘all their furnishing fabrics were made in England’, Harding was not oblivious to what the wider world could offer, claiming to be able to supply ‘every article of foreign manufacture which there is any possibility of obtaining’. A demand for lace led him to establish a lace factory on the premises, headed by a Flemish expert who would instruct ‘young women respectably connected and of good conduct’ in the art of lacemaking for a fee of £10 each. He would also export goods around the world.

Harding was also saw innovation as a means of keeping ahead of his competitors. A newly patented permanent green dye for chintz, for which he secured the sole trading rights, was advertised as ‘a discovery never before offered to the public’. In 1807 he quickly recognised that the newly installed gas lighting in Pall Mall, the first street to be so illuminated, would show off his printed chintzes and textiles to great effect if they were displayed in the window. Some of his claims, though, strained credulity. A hair dye was advertised as ‘the best Dye in the universe for immediately changing red or grey hair’.

Shoplifters felt the full force of the law. In 1799 Mary Wilson, aged forty-seven, was found guilty of stealing goods to the value of twelve shillings, namely some black ribbon, two pairs of cotton mittens and a silk handkerchief, a crime for which she was sentenced to seven years transportation. She died in Newgate prison two months after her trial.

However, by the standards of the time, Harding was remarkably lenient towards crimes committed by his own employees. In 1817 Samuel Arnold stole £74 in cash and £35 in promissory notes, a crime punishable by death. At his trial at the Old Bailey, he was found guilty, but a director of Harding’s spoke in his favour, describing him as a trusted employee who had always ‘acted honourably’ and whose lapse was down to the malign influence of his new wife. When he declared that Harding’s would have Arnold back, there was ‘a buzz of applause’ in the court room, moving the judge to spare the prisoner who was promptly re-employed.

In December 1819 the business moved to 9, Regent Street, opposite Carlton House. Shoppers were by now buying goods on a whim rather than out of necessity, an appetite fed by Harding’s willingness to be ‘quite prepared to offer a regular succession of novelty throughout the season’. Their fame spread as far as China where a correspondent in 1834 reported a demand for things ‘pretty, odd, and new at Howell’s and Harding’s’. The company’s Royal Warrant as ‘Silk Mercer by Appointment’ to Queen Victoria was a major feather in his cap.

Harding was said to be the last man in London to wear a queue — a type of ponytail added to a wig — and a prodigious drinker who, ‘although never drunk, lost the use of his legs after the sixth bottle’ (this was apparently an occurrence so frequent that a special chair had to be constructed to carry him to bed). He lived a long life, despite all that: Harding died in 1851 aged eighty-nine. His shop soldiered on for a few years but had closed by 1859 when the War Office took on the premises.

As department stores continue to fight for their existence, it is timely to think of the man who first brought them to London’s streets.

Who started the first charity shop?

Charity shops have become a staple of British high streets in the past decade, and more and more of us

Credit: Alamy

Curious Questions: Who invented the cardboard box?

Six months of online shopping have left Martin Fone buried in cardboard boxes — and that's put him in the

Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Curious Questions: Which came first — the plastic flower pot or the garden centre?

Martin Fone takes a look at the curiously intriguing tale of the evolution of nurseries in Britain.

Curious Question: Why does the air smell so good after it's been raining?

That wonderful scent in the air when the rain stops falling has entranced people since the dawn of time —

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.