Donald John Mackay, the Hebridean tweed weaver who has changed an entire industry

Given the chance create his very own ‘estate’ Harris tweed, David Profumo knocks at the door of Donald John Mackay, the Hebridean weaver who has changed an entire industry. Photographs by Glyn Satterley.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It is the only time I have walked out of a restaurant with a pair of my father-in-law’s trousers over my arm. For a significant birthday, The Doctor (as he is known) had arranged for me to have a specially woven Harris tweed version of his own venerable sporting suit and he was loaning me the original as a template. Although I am only the laird of a modest Highland hill farm, I have always loved the concept of having my very own ‘estate tweed’.

When, many years ago, he bought her Hebridean croft, The Doctor was given by old Mrs Macmillan a traditional length of homespun she had woven there herself in the outhouse and he has worn it proudly ever since. Over the decades that I have been visiting the island, I, too, have developed a penchant for tweed, a textile of subtle beauty that somehow reflects the texture and earthy palette of the local landscape — it is hard-wearing, handsome and keeps me snug when the central heating fails up the glen here.

Clò Mòr (or ‘big cloth’ in the Gaelic) began to be popularised away from its homeland when, in 1846, the Dowager Lady Dunmore had her family tartan replicated in Harris tweed and the fashion spread among Scottish landowning circles (a Balmoral check was developed in 1853). Its non-pareil durable qualities eventually became so popular with climbers, dedicated shootists and cyclists of all genders that shoddy imitations proliferated — one fake was so loosely constructed that an islander contemptuously said: ‘You could spit peas through it.’ A Lancashire mill even devised a spray to mimic the genuine article’s distinctive scent and, more recently, an Italian company was advertising ‘Harry’s Tweed’. (The word ‘tweed’ itself resulted from the misreading of a labelled consignment of ‘tweel’ that, in 1832, was dispatched to London from Hawick in the Scottish Borders and shares no historic identity with the mighty river of that name.)

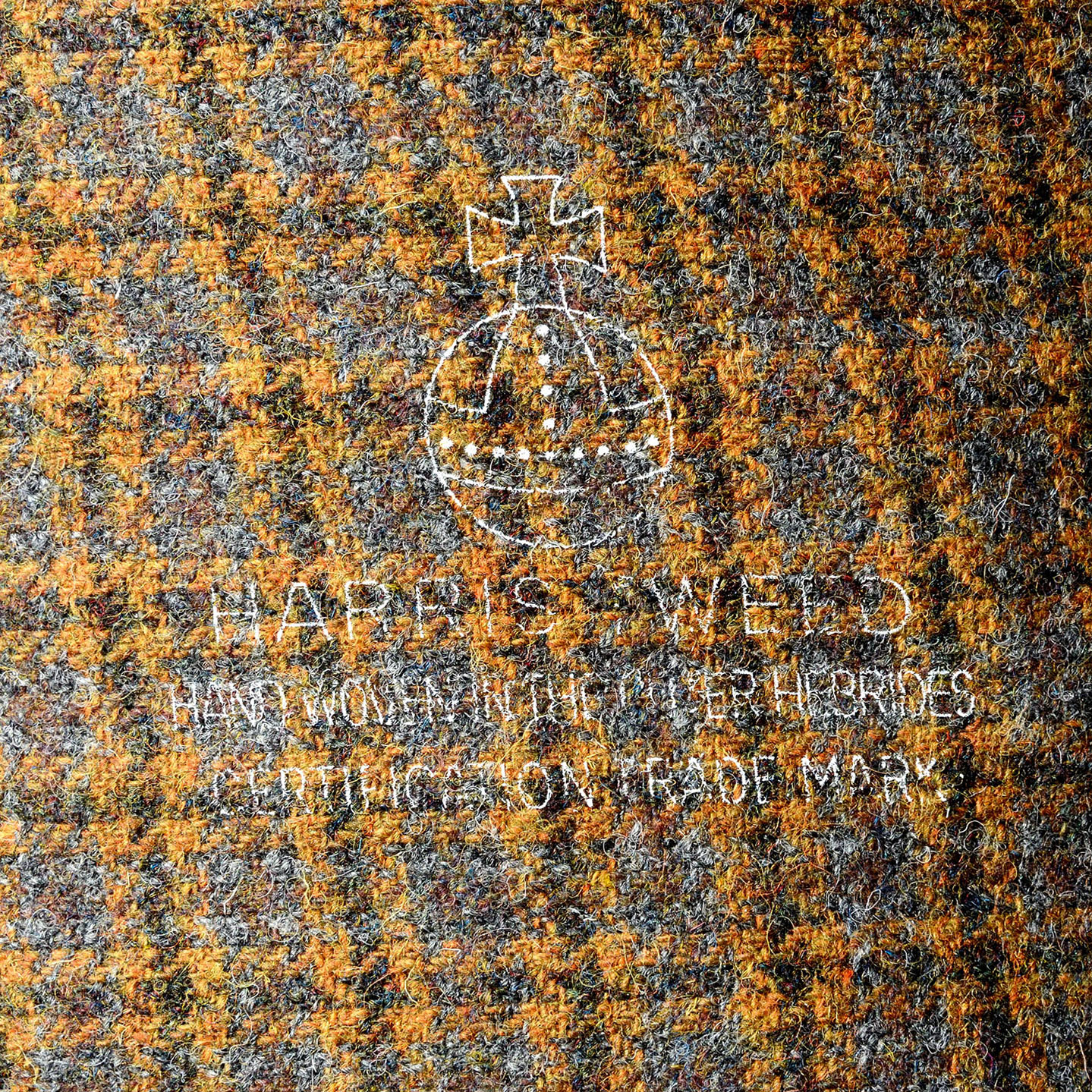

So crucial was it to safeguard the exacting standards of this small-scale cottage industry that, now, Harris Tweed is the only fabric in the world governed by its own Act of Parliament. Since 1993, the term — and its distinctive Orb trademark — can only be applied to cloth that is entirely dyed, spun and handwoven by Hebridean artisans in their homes. Vagaries in taste and image have always affected it: in the loom-boom year of 1970, for example, nearly eight million yards were being produced, but, by 1995, this had slumped to only 1½ million. Periodically, it is re-adopted on the international catwalks — Vivienne Westwood, Ralph Lauren and Alexander McQueen have all been tweedy designers at times — yet the most dramatic saga in the textile’s tangled history involved the very man who was later to create our own family fabric.

One day in 2004, Donald John Mackay, a third-generation independent crofter-weaver at Luskentyre, south Harris, was busy at his loom when his wife, Maureen, announced there was a company called Nike on the telephone. ‘I didn’t know who they were,’ he says, but they requested a few samples. ‘To be honest, I didn’t expect to hear anything back.’ When Nike subsequently rang in an order for 10,000 yards of cloth, it caused him ‘sheer panic’ — his daily output averaged some 27 yards.

He mobilised most of the weavers in the Western Isles, the order was filled in three months and a limited-edition female training shoe, the Terminator, was duly launched — with the Orb appearing on its tongue, alongside the Nike ‘tick’. Madonna was among those who sported it and further commissions ensued — it proved a turning point for the entire Harris tweed industry.

Modest, courteous and outspoken, Mr Mackay is a veritable ‘local hero’ and was made an MBE by the late Queen in 2012. He continues to produce limited quantities of traditional, single-width cloth on his foot-treadle Hattersley loom and, when we visited to discuss a new, unique iteration of The Doctor’s weave, he showed us the painstaking method by which all his tweeds are crafted.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

First, dyed yarns are set up by hand to determine the pattern by intricate vertical threads (the load-bearing warp) and the weft that runs left to right. Commercial dyes are now standard, but, within living memory, natural dyestuffs such as crotal lichen or peat soot were used, often fixed with urine as a mordant. Once the web has been woven, it is finished by washing and shrinking it at an island mill — formerly a laborious process performed by women at a ‘waulking’ board, to the rhythm of Gaelic songs.

It took some months to decide upon the final design. Nonetheless, in due course, there was a presentation ceremony here in Perthshire, when The Doctor unrolled the finished bale. We had settled for a medium-weight tweed, its ground a smoky grey like the island bedrock, with over-check and tones of bracken and golden moss. It smells deliciously of peat-smoke and lanolin. Mr Mackay pronounced himself pleased with his handiwork: ‘If you wore that on the hill, well — you’d disappear,’ he said, approving of its natural camouflage colours.

Now, we had to find a bespoke tailor to build garments from this magical cloth and the obvious choice was Campbell’s of Beauly — established as a family firm back in 1858 and now owned and run by the enterprising John and Nicola Sugden. Helen, my wife, had a fetchingly waisted jacket made and I plumped for a coat, long trousers and proper plus-fours, with a cap (but skipped any matching trainers). As you would expect from a firm that makes sporting tweeds for more than 100 estates and enjoys royal patronage, the finished garments were immaculate.

We were now dressed to kill — and the first expedition was, fittingly, to Amhuinnsuidhe Castle in North Harris, erstwhile home of the Dunmores themselves. I caught two salmon that day, which I hope bodes well. And I feel sure — given their fabled durability — these tweeds will see me out. My birthday card read: ‘Wear them well.’ Doctor, I certainly will.

For information about the Luskentyre Harris Tweed Company, telephone 01859 550261 or email Donald John Mackay at djluskentyre@gmail.com. For tailoring rates and apparel at Campbell’s of Beauly, Inverness-shire, telephone 01463 782239 or visit www.campbellsofbeauly.com