Curious Questions: Can you hear the Northern Lights?

The Northern Lights — or Aurora Borealis — are among the planet's most extraordinary natural phenomena. Even stranger than their ethereal glow, however, is the fact that they can be heard as well as seen. Martin Fone explains more.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Swirling rivers of greenish-blue light against a clear sky, dancing seemingly with a will of their own, sometimes almost static, the Northern Lights — or Aurora borealis — are one of nature’s most spectacular displays. For all their beauty, though, they are the product of a violent event high above us, the clash of charged particles from the Sun with the Earth’s magnetic field.

Solar winds send energised particles from the Sun’s surface, hitting the Earth’s upper atmosphere at speeds of around 45 million mph. Acting as a defensive shield, the Earth’s magnetic field forces the charged particles to move in spirals along the magnetic field lines towards its magnetic poles. Once they hit the gas atoms and molecules in the Earth’s atmosphere, they transfer their energy which is transformed into photons.

The Northern Lights’ colour is dependent upon three factors at the time of the collision: the amount of energy held in the solar wind’s electrons, the type of gas atoms and molecules they collide with, and the altitude at which it occurs. A red light is produced when high-energy electrons interact with oxygen at an altitude in excess of 290 kilometres in the ionosphere while the more familiar green light is the result of the impact of low-energy electrons and oxygen at lower altitudes. A collision with nitrogen can produce a blue or red hue and other colours such as pink or purple are created when there is a mix of gases.

As the solar wind particles are funnelled towards the Earth’s magnetic poles, aurorae are most likely to be seen in a circular area around them, in the northern hemisphere, principally around the northern coast of Siberia, Scandinavia, Iceland, the southern tip of Greenland, northern Canada, and Alaska. When solar activity is particularly intense, as at the end of February 2023, they are visible much further south.

The southern hemisphere has its own lights, the zone passing mostly over Antarctica and the Southern Ocean and are normally visible from land in Tasmania with occasional sightings in southern Argentina and the Falklands.

Aurorae are not intermittent events but happen all the time, a fact brought vividly to life by The Space Weather Prediction Centre’s fascinating interactive forecast of the location and intensity of an aurora in the world over the next thirty to 90 minutes. Whether we see them or not is dependent upon sky conditions and the level of light pollution.

Named Aurora borealis by Galileo in 1619 and explained scientifically by Norwegian physicist, Kristian Birkelan, in 1902/3, the Northern Lights have long fascinated mankind, featuring in cave paintings found in South-western France dating to 30,000 BC, and first recorded by a Babylonian astronomer in 567 BC. Absent a rational explanation for their cause, they inspired many myths and superstitions.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

For the Vikings, they were the shimmering reflections of the armour of the Valkyries sent by Odin to collect the bodies of the warriors slain in battle, while in Finland fire foxes travelled through the sky so quickly that their tails produced sparks as they brushed the mountains. In northern Sweden the lights, created by shoals of herrings, were a harbinger of a plentiful catch.

Elsewhere they represented the souls of the dead, in Greenland of children who had died in childbirth and in Norway of old maids, while for the Sámi they were to be feared and respected. Provoking them by waving or whistling in their presence ran the risk of being snatched away. In Scotland, the lights, known as ‘Merry’ or ‘Pretty Dancers, were created by fallen angels and warriors who battled it out in the skies, their drops of blood creating the distinctive red specks on the green heliotrope known as bloodstone.

Their ominous red presence in the skies of continental Europe was seen as a harbinger of war. In the weeks before the French Revolution a bright red Aurora was seen over Scotland and England with reports of the sound of mighty battles being heard, intriguingly raising the question of whether the Northern Lights made a noise.

One who took the subject seriously was Danish astrophysicist, Sophus Tromhult, inspired by his father, Johan, who claimed to have heard them three times between 1838 and 1843. He likened their sound to the quiet but rapid rubbing together of two pieces of paper. Despite a career spent observing the lights and being the first man to photograph them, in October 1882, Sophus never heard them.

In the 1930s The Shetland News was inundated with reports, some contemporary, others historic, of sounds emanating from the Northern Lights. One such, published on May 20, 1933, from Peter Hutchison claimed that ‘on clear and frosty nights about thirty years ago the ‘pretty dancers’…would flit and fro, making a noise as if two planks had met flat ways – not a sharp crack but a dull sound, loud enough for anyone to hear. We boys got so used to this that we never heeded the noise when the pretty dancers came out to clap their hands’. Witnesses in Canada and Norway also claimed to have heard them.

Persistent reports of noises emanating from aurorae were discounted by the scientific community, the witnesses having no rigorous scientific training and the altitude at which they occurred being beyond the range of human hearing. The tide turned when the eminent auroral scientist, Carl Størmer, published the experiences of two of his assistants who described hearing ‘a very curious faint whistling sound, distinctly undulatory, which seemed to follow exactly the vibrations of the aurora’ and a sound like ‘burning grass or spray’.

A paper published by Clarence Chant in The Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada in September 1923 provided the now accepted scientific rationale behind the sounds emanating from aurorae, although there is still some debate as to how the mechanism that produces the sound operates. The motion of the Northern Lights, he explained, altered the Earth’s magnetic fields, inducing a change in the electrification of the atmosphere which, in turn, generated a crackling sound much closer to the Earth’s surface when it met objects on the ground, much like static. It was not until the 1970s that Chant’s theory was rediscovered.

Some experts argued that the chances of hearing an aurora were remote, with only 5% of violent auroral displays accompanied by sounds. However, some recent research by Professor Emeritus Laine of Aalto University has turned this on its head, suggesting a remarkably strong correlation between geomagnetic fluctuations and auroral sounds. Astonishingly, Laine claims that that many of what he calls ‘possible auroral sounds’ occur even in the absence of visible Northern Lights. In other words, it is possible to hear them even if you cannot see them, and that without a visual accompaniment the sounds made by the Northern Lights might easily be passed off as something more mundane.

To hear a version of them, check out a Radio 3 programme in the Between The Ears series, first aired on Boxing Day, 2020, which remapped very low frequency radio recordings of aurorae to levels audible to the human ear. Although not quite the same as the real thing, it suggests that the Northern Lights should be reclassified as one of nature’s finest son et lumière shows.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Who invented the lawnmower?

Martin Fone delves into the history of the lawnmower and discovers a link to weaving machines.

Curious questions: Who was the first person to receive the Victoria Cross?

Martin Fone retraces the history of the order and discovers the stories of its early recipients.

Curious Questions: How fast do snowflakes travel?

Martin Fone examines the science behind snow and explores the history of snowfalls in the UK.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Should you bring a snowdrop into the house?

Martin Fone delves into Britain's collective passion for Galanthus and looks at the folklore that surrounds it.

Curious Questions: Why were ferns considered magical?

Martin Fone considers the beautiful and ancient fern, once commonly held to have mysterious properties.

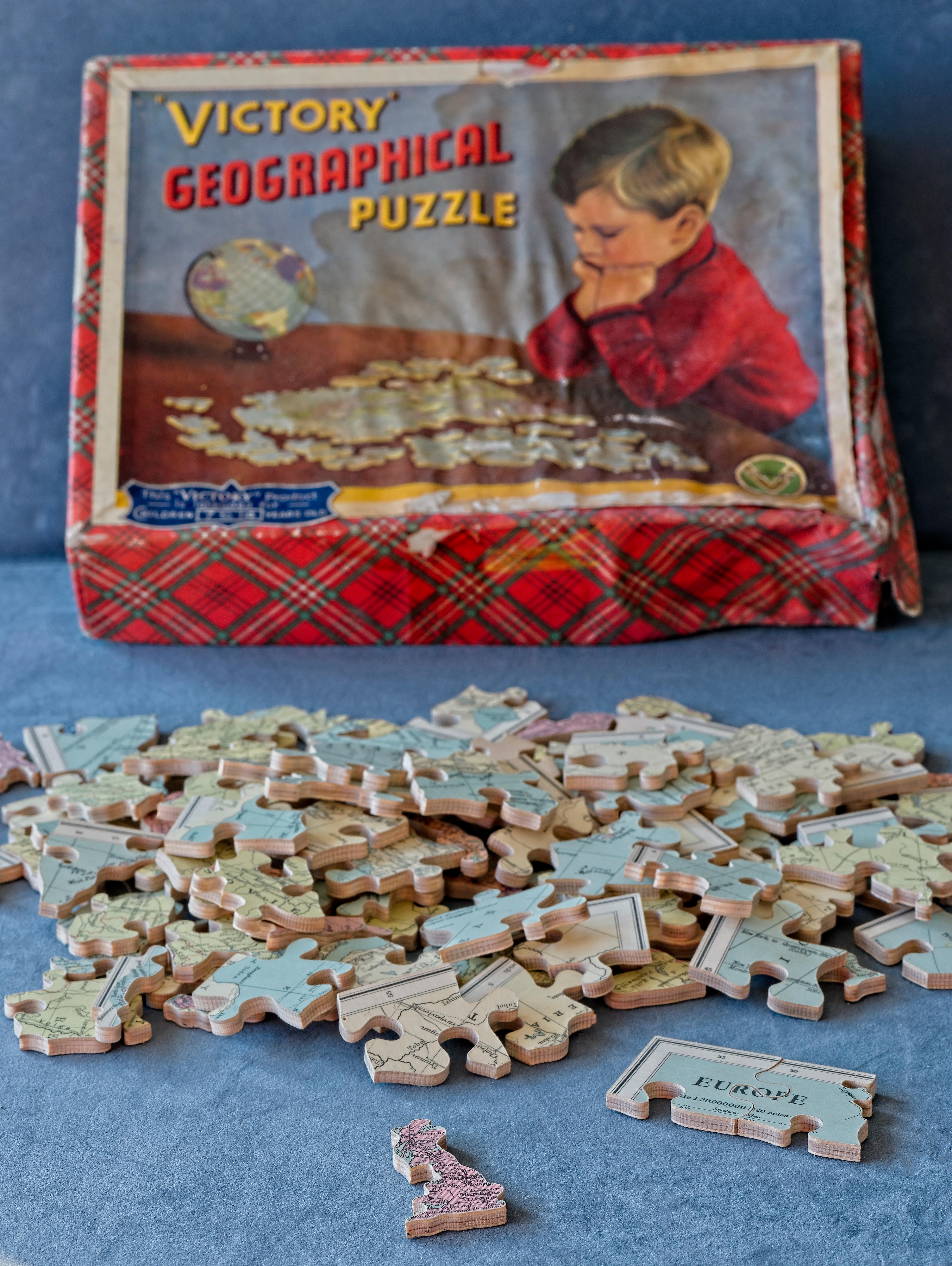

Curious Questions: Why do we call picture puzzles 'jigsaws'?

Jigsaws have been around since the 18th century and have gone through all sorts of iterations. Martin Fone traces their

Credit: Alamy

Curious Questions: Why are pineapples called pineapples, when they're not pines and not apples?

Martin Fone delves into the curious history of one of the world's most popular tropical fruits.

Credit: Getty

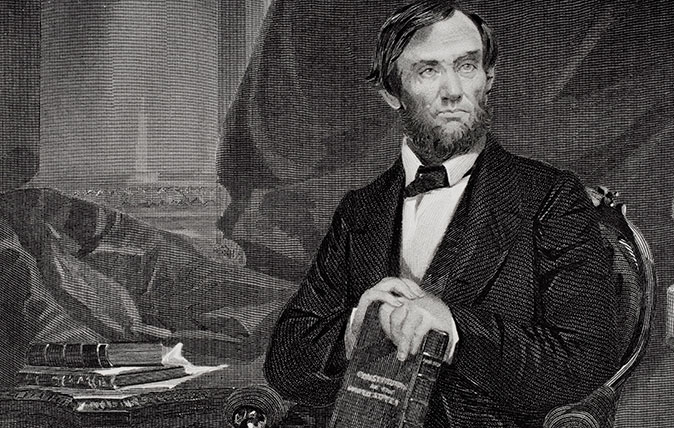

Curious Questions: How did Abraham Lincoln come to be the only US president to hold a patent?

Statesman, lawyer, fearless leader – and part-time inventor. Martin Fone looks at one of Abraham Lincoln's lesser-known talents.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.