Curious Questions: Were Mallory and Irvine the first to reach the summit of Mount Everest?

It’s now 100 years since George Mallory and Andrew ‘Sandy’ Irvine disappeared high on Everest; speculation about their achievements has been rife ever since. Robin Ashcroft takes a broad perspective

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At about lunchtime on June 8, 1924, Noel Odell was at more than 26,000ft on Everest, climbing in support of George Mallory and Andrew Irvine. It was a calm, but cloudy day and the Northeast Ridge was wreathed in mist. At 12.50pm, there was a break in the cloud and Odell noted in his diary: ‘Saw M & I on the ridge nearing the base of the final pyramid.’

Odell would later elaborate, if not clarify: ‘I noticed far away on the snow slope leading up to what seemed to me, to be the last but one step from the base of the final pyramid, a tiny object moving and approaching the rock step. A second object followed, and then the first climbed to the top of the step.’ As the cloud thickened, it was the last time they were seen alive: the ‘mystery of Mallory and Irvine’ was born.

There are three steps on the ridge, but, in 1924, no one was familiar with the detailed topography of the ridge’s crest, as it was still terra incognita. We now know, however, that only the ‘Second Step’ presents a major challenge, but it is one that is formidable.

Personal tragedy apart, the sadness around the 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition is that speculation over Mallory and Irvine’s achievements came to overshadow recognition of those of others. After Mallory’s US lecture tour in 1923, he’d become something of a media celebrity and ‘because it’s there’ was already common parlance. Celebrity is often magnified by death, distorting a wider perspective.

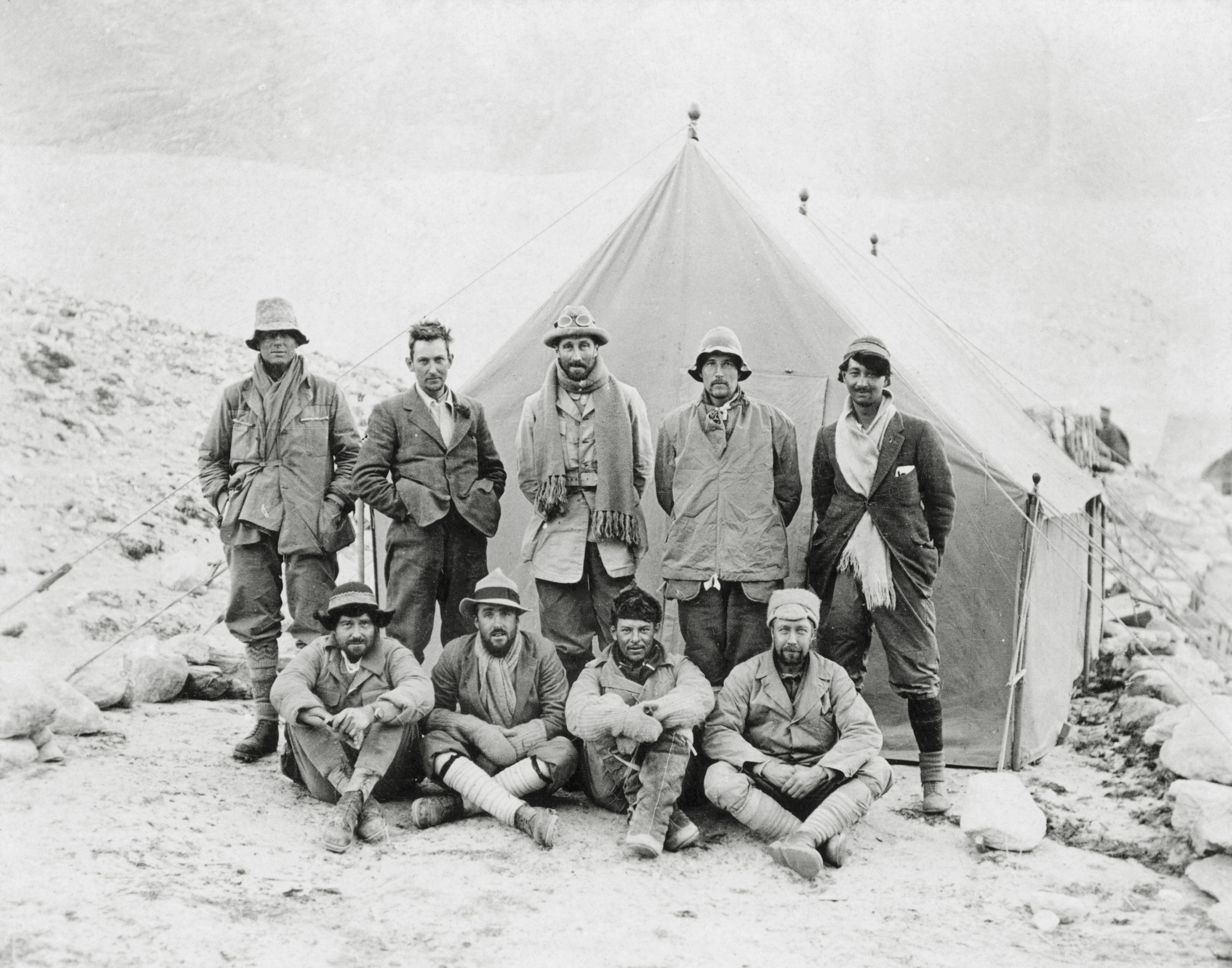

A team photograph was an established Everest tradition by then and that from 1924 showed a remarkable group of men. Previously, George Bernard Shaw had pithily described the 1921 expedition as a ‘Connemara picnic surprised by a snowstorm’ after seeing their photograph. They did appear to be dressed more for the grouse moor than for the Himalayan heights, but, by 1924, the climbers were remarkably well equipped. They wore windproof outer clothing, multiple insulating layers and a highly effective design of boot—all have subsequently been proven to compare well with modern expedition attire.

Given British social mores of the time, they would have deplored being seen as too professional in their approach, but they were highly competent. Not least Edward — ‘Teddy’ — Norton, who stands in the middle of the photograph, complete with a woollen scarf to lend a schoolboy air to his demeanour.

Looks, however, can deceive; he had climbed in the Alps since his teens, had performed strongly on the 1922 Everest Expedition and was, by then, a lieutenant-colonel and veteran of the First World War with a DSO and MC. Below and to his left sits Howard Somervell. He, too, possessed a fine climbing record, both on his native Lakeland fells and in the Alps. Latterly, he had served with distinction as a Regimental Medical Officer on the Western Front and had done well on Everest in 1922.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

At 6.40am on June 4, Norton and Somervell left Camp VI — at 26,800ft — on the expedition’s second summit attempt. Climbing without bottled oxygen, they took a line below the crest of the Northeast Ridge and its three steps, making good progress until Somervell had to halt. Days earlier, he had strained his throat when rescuing a group of Sherpa and this now led, with his inevitable panting in the freezing air, to a frostbitten larynx.

'Mallory had cast aside his previous objections about oxygen being "unsporting" and would now use it'

Norton pressed on alone to reach a key feature on the mountain’s north face, the Great or Norton Couloir: ‘Beyond the couloir the going got steadily worse; I found myself stepping from tile to tile, as it were, each tile sloping smoothly and steeply downwards; I began to feel that I was too much dependent on the friction of a boot nail on the slabs.’ About 900ft below the summit, he thought it wise to retire, having set an altitude record of 28,126ft that would stand until 1952.

Mallory had already led the expedition’s unsuccessful first summit attempt, but — possibly keen to secure both the first ascent and the ensuing publishing royalties — persuaded a now snow-blind and weakened Norton to let him have another crack at the top. He chose ‘Sandy’ Irvine, rather than the proven mountaineer Odell, as his partner.

Aged 22, Irvine had precious little climbing experience, but was a remarkable athlete nonetheless — he had rowed in the Boat Race — and had a resolute, adventurous spirit. Already an Arctic explorer, he was also the first to drive a car over the Lake District’s notorious Hardknott Pass. His selection by Mallory was probably due to his engineering skills and his ability to keep the temperamental oxygen sets going. Knowing, at 37, that this may be his last throw of the dice, Mallory had cast aside his previous objections about oxygen being ‘unsporting’ and would now use it.

Assuming he reached it, Mallory was the first to get anywhere near the Second Step and, until then, would have been unaware of its difficulty. It was only climbed ‘free’ — with no ladder or aid — in 2007 and is now given a grade of at least ‘Hard Very Severe’. At that time, in the British mountains, this would have been at the top of any climber’s grade (even Mallory’s). At more than 28,000ft, it would have been nigh impossible within Odell’s cited timeframe.

Mallory’s body was found in 1999; he had clearly fallen during the descent, most likely after dusk. It’s frustrating that no hard evidence was gained from this discovery to prove if the pair had reached the summit. It was likely Irvine carried their camera and the absence on the corpse of the photograph of Mallory’s wife — which he’d promised he would leave on the summit — is, given the ferocity of the winds on Everest, clutching at straws.

The reality, however, is more prosaic: Mallory and Irvine simply would not have had sufficient drinking water to perform well enough to reach the summit. Issues around clothing, oxygen and even the Second Step are distractions. Everest has now been climbed many times without supplementary oxygen and research conducted on the clothing recovered from Mallory’s body shows it was fit for the task in hand. However, every account of the early Everest expeditions tells of how climbers suffered from ‘raging thirst’.

It was only understood later, following research during the Second World War, just how critical it is to be fully hydrated at altitude, then how Primus stoves could be adapted to work efficiently enough to melt ice so high. With this knowledge, the planning for the 1953 Everest Expedition focused on the climbers drinking at least five to seven pints a day, whereas they struggled to produce a pint per man on their summit attempts in the 1920s.

Success is vividly illustrated by Sir Edmund Hillary’s account of his final act before leaving Everest’s summit: ‘I had to pee!

Curious Questions: Why did the Garden Cities of Tomorrow never catch on?

The worst excesses of the Industrial Revolution prompted some truly forward-thinking urban planning as far back as the 19th century

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?

Beatrice Harrison, aka ‘The Lady of the Nightingales’, charmed King and country with her garden duets alongside the nightingales singing

Credit: Bettman/Getty Images

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?

There are few things less pleasurable than a tuneless public rendition of Happy Birthday To You, says Rob Crossan, a

Curious Questions: Who was the first person to take a driving test?

For years, all you need to drive a car was to jump behind the wheel — but that all changed.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.