Jason Goodwin: 'On our watch, the natural glories of our island have been atrociously depleted'

Our columnist Jason Goodwin laments the staggering decline of British wildlife and the depletion of our island's natural glories.

The countryside looks green. There are trees. There are blowsy hedgerows, grass verges and the odd dead badger in the gutter. You’ll see plenty of what my father-in-law called American tree rats. There are birds, too. It’s just that there aren’t enough of them. Not enough insects to make a cloud, not enough birds to darken skies, too few water rats to make a splash. Where we should have buzzing, fluttering, rootling and boring, there’s silence.

Underfoot, the soil is weak; by one estimate, we have only 100 harvests left before the earth itself, crushed, poisoned, scraped and compacted, blows away. Instead of supporting 60 kinds of beetle, the dung of animals treated with livestock wormers and parasiticides is sterile.

We pride ourselves on being a nation of country lovers, members of the National Trust, the RSPB, heritage societies and conservation groups dedicated to the protection of our natural patrimony. But, on our watch, the natural glories of our island have been atrociously depleted.

Since the Second World War, Britain has become one of the least diverse, species-rich and ecologically thriving countries in the world. We’re ranked 199th out of 218 countries. We’re crowded and encroached upon and we insist on growing too much of our own cheap food.

'One in five British wild mammals faces danger of extinction in the next 10 years'

The statistics are all there, if statistics are your thing, from the 67% decline in the numbers of toads, skylarks and beetles in 50 years, to the danger of extinction that faces one in five British wild mammals in the next 10 years.

Of course, there have been success stories. The short-haired bumblebee has been reintroduced successfully at Romney Marsh, having been declared extinct in 2002. But how come it vanished in the first place?

We had 11 male bitterns in 1997. Now, after legal protection and the creation of reed beds, there are 156. Is 156 bitterns a lot?

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In a period when the human population of these islands has increased by almost eight million people, 145 extra bitterns doesn’t seem terribly significant. The heartening new book, Wilding, by the aptly named Isabella Tree (Book review, May 2), suggests a more radical alternative to pricey, piecemeal protection schemes.

In possession of 3,500 acres of intractable Wealden clays at Knepp Castle in West Sussex, she and her husband ditched modern farming with its inputs, outputs and scalability and took a flying leap into peaceful co-existence with Nature.

The effect, 17 years later, is little short of miraculous: the re-emergence of a teeming scrubland supporting hundreds, thousands, of lifeforms that nobody expected to see again, including thickets of nightingales and damp hoofprints wriggling with fairy shrimps.

The hoofprints are left by longhorn cattle, aping the aurochs of yore, and Tamworth pigs stand in for wild boar. At the top of the food chain with herds of deer, they set the tone for everything that cascades out below them – and pay the author in organic meat.

The untamed landscapes that have emerged are indeed bewildering, but in permitting the return of rare species, from nightingales to the purple emperor butterfly, Knepp is turning established conservation practice on its head. In a minimally managed environment, flora and fauna from creeping fescues to soaring turtle doves are revealing their true habits and proclivities, not as creatures surviving in a manmade countryside at the limits of their own range, but thriving as wild animals in a wild world.

Miss Tree’s point is to try less to conserve our landscapes, like jam in a sealed pot, but to find, between farmland and streetscapes, new regions where Nature can steal in, to reclaim those purposes that existed before we, as a species, ever knew the meaning of shame.

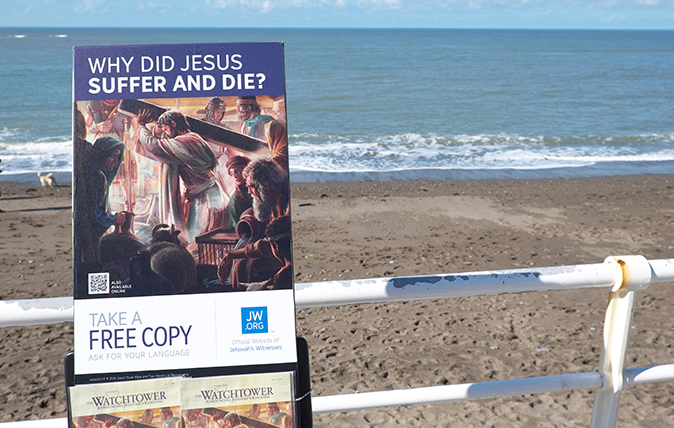

Jason Goodwin: Keeping up with the Jehovahs

'I don’t get into theological debate with them; I simply like to bask awhile in their radiant happiness'

Credit: Tim Gainey / Alamy Stock Photo

Jason Goodwin: ‘The only sounds were the yawning of dogs, the spitting of logs in the fireplace and the occasional papery gulp of somebody turning a page’

Snowed in and without power, Jason Goodwin was left to live a medieval lifestyle that was rejuvenating and romantic... but

Credit: Getty

Jason Goodwin: 'There was nothing there. The original message from St Petersburg, Sergei’s emails, the thank-you email. All gone.'

Our columnist Jason Goodwin recounts a chilling tale of his own brush with the Russians in Dorset.

Jason Goodwin: 'I think about it when I’m on the stepladder, reaching out dangerously far to tweak a ripe fig'

Jason Goodwin tells our readers why he's now decided to give a fig about the ancient fruit that's been growing