Curious Questions: Who dislodged Britain's most famous balancing rock?

A recent trip to Cornwall inspires Martin Fone to tell the rather sad story of the ruin and restoration of one of Cornwall's great 19th century tourist attractions: Logan Rock at Treen, near Land's End.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

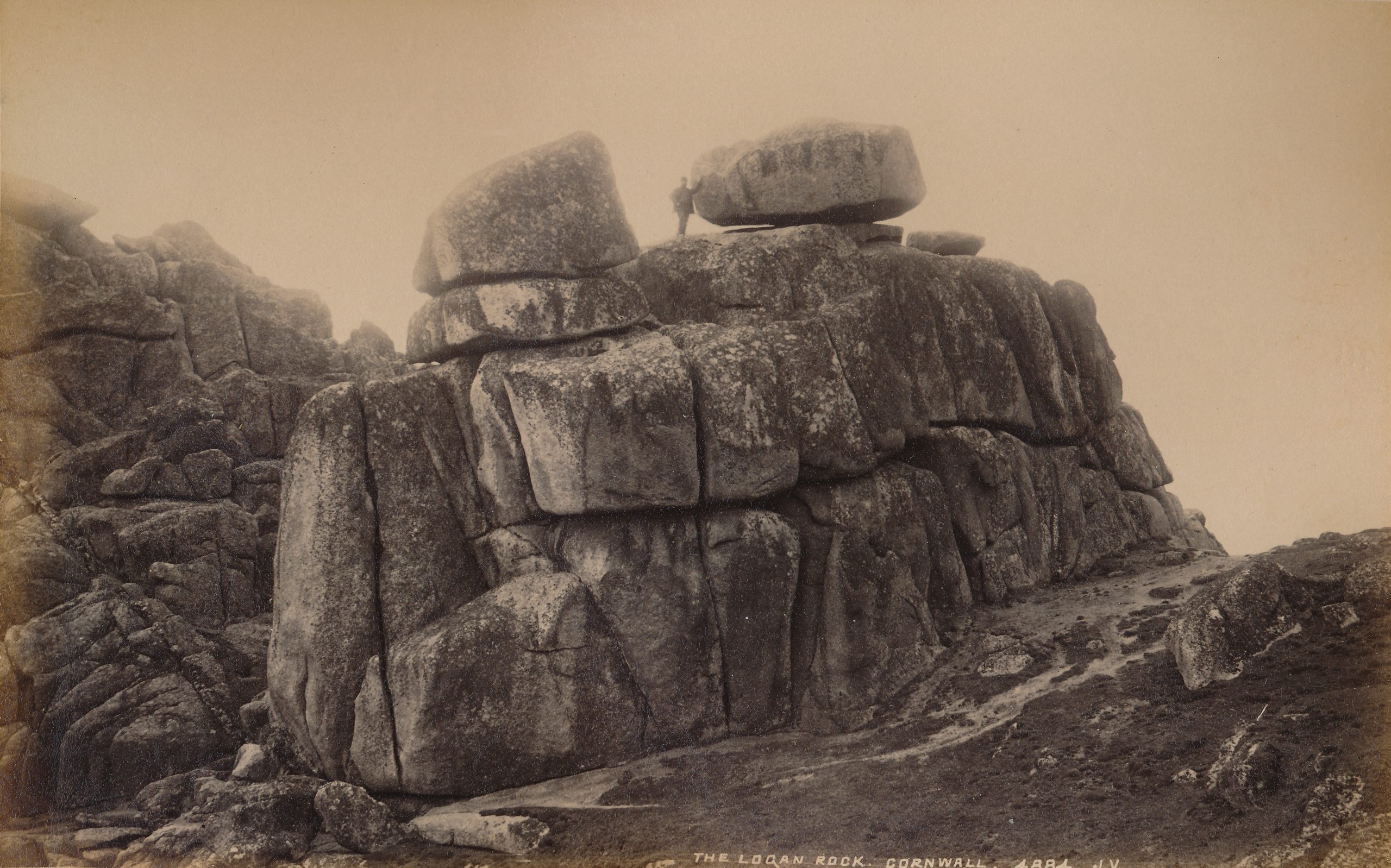

Men Omborth, Cornish for ‘balanced stone’, sits about thirty metres above the sea on top of the Teryn Dinas cliffs at Treen in the far west of Cornwall, about three miles or so from Land’s End.

Known as a ‘Logan’ or logging stone — from the Cornish word ‘logging’ meaning rocking — it is one of several pieces of detached rock to be found in the county that are poised so finely on their base that they move backwards and forwards under the slightest of pressure.

They were once thought to be the work of human hands, connected with Druidic rituals and religious ceremonies. Legend had it that a person’s guilt or innocence could be established by a rocking stone; it would vibrate if they were guilty and remain stationary if guilty. Alternatively, according to William Mason’s Caractacus (1759), ‘it moves obsequious to the gentlest touch/ of him whose breath is pure; but to a traitor, though even a giant’s prowess nerved his arm, it stands as fixed as Snowdon’.

More prosaically, their shape and position are the result of a combination of glacial movement, erosion, weathering, and the laws of physics. A Mr Grove went to great lengths at a British Association meeting, reported The Trove in November 1890, to demonstrate that logan stones were the result of natural rather than human forces, having ‘by artificial attrition…made several miniature rocking stones’.

He showed ‘how by the action of the atmosphere on their corners, many large masses of rock, which have a tendency to disintegrate into cubical or tabular blocks, might gradually become rounded into the rude spheroidal shape generally presented by the logan’

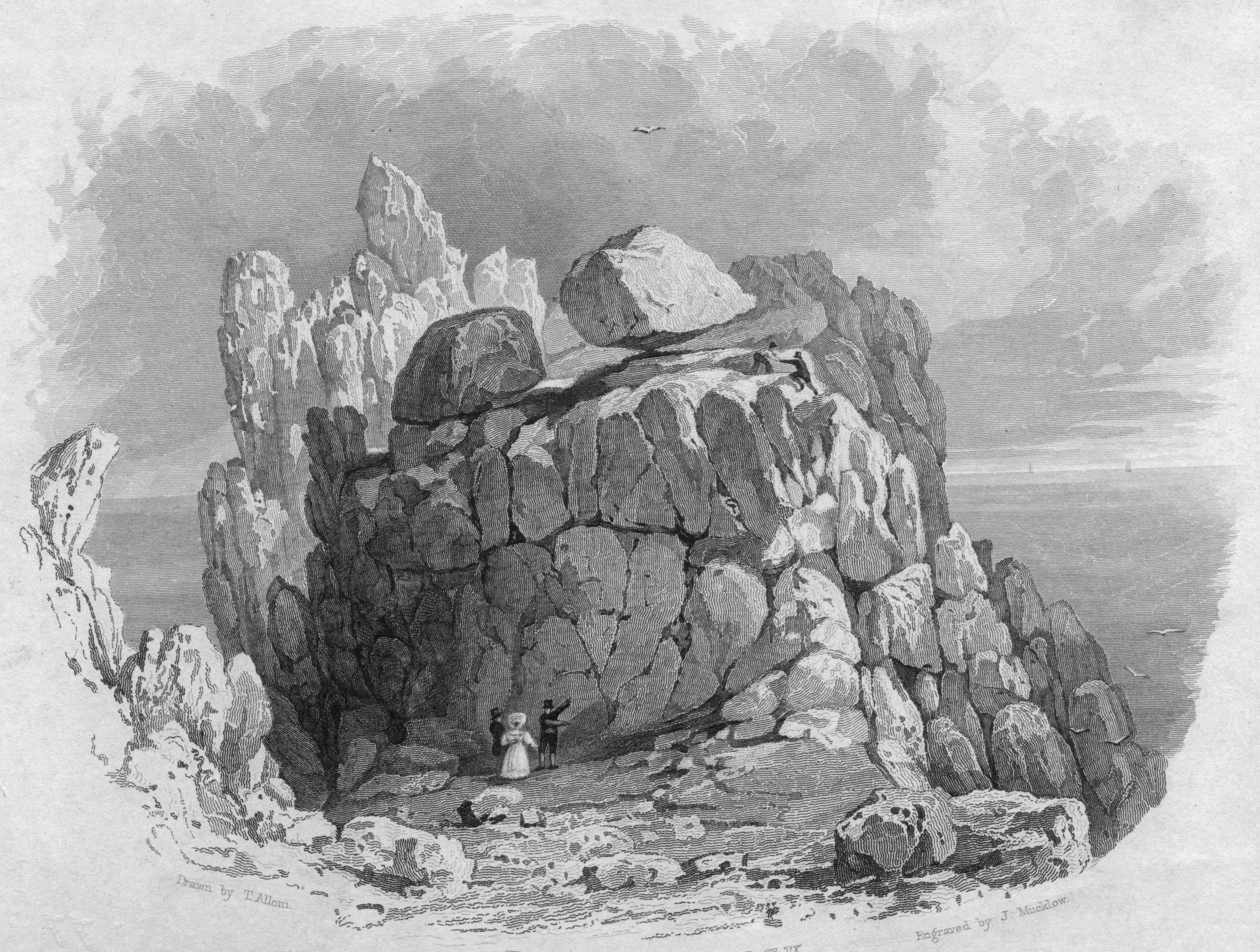

Cornwall’s most famous logan, Men Omborth drew visitors from far and wide to gaze upon what Mason described as ‘yon huge/ and unhewn sphere of living adamant,/ which, poised by magic, rests its central weight/ on yonder pointed rock’ and perhaps even see it move. It became famous, with people coming to visit from far away and artists descending to capture its uncanny nature in pictures such as the one you see at the top of this page.

‘So evenly poised’ was it, wrote Dr William Borlase in Antiquities of Cornwall (1754), ‘that any hand may move it to and fro; but the extremities of its base are at such a distance from each other and so well secured by their nearness to the stone which it stretches itself upon, that it is morally impossible that any lever, or indeed force, however applied in a mechanical way, can remove it from its present situation’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Royal Navy had other ideas.

It is always dangerous to leave a hostage to fortune, and especially when the Navy is around. Their intervention came 70 years after Borlase’s words when Lieutenant Hugh Goldsmith, nephew of the poet Oliver Goldsmith, came to the site aboard the small ship he commanded HMS Nimble — a six-gun revenue cutter which patrolled the Cornish coastline on the lookout for smugglers and attempting to seize their contraband. On April 8, 1824, finding themselves off Treen and close to the famous logan, he and nine of his crew decided — in a moment that must surely have been at least partly fuelled by the generous Naval rum rations of the day — to see whether Borlase’s assertion held water.

At around 4.30pm armed with three handspikes, they set about trying to lever the stone from its pivotal rock. As it would not budge, the men then rocked the stone with such vigour that Goldsmith, fearful that it would fall on to them, gave the command for them to stop. It was too late, though, and while the stone missed the party, it toppled off its mound and fell some feet, an outcrop of rocks breaking its fall and stopping it from plunging into the sea.

Once news of Goldsmith’s act of folly reached Penzance, it roused the sort of righteous indignation that only the strict application of Law 20.1.2 in cricket can today. A local worthy named Sir Richard Vyvyan of Trelowarren vowed that he would ‘prosecute the delinquent with the utmost vigour’ and once the Royal Cornwall Gazette had given the story due prominence, it was picked up by the national papers. Pressure was put on the Admiralty to restore the focal point of Treen’s tourism industry, something which many eminent engineers at the time thought could not be done.

Realising that he was in hot water and fearing for his safety, a contrite Goldsmith confided to his mother on April 24th in a letter that he was taken aback by the reaction he had provoked. ‘I knew not’, he wrote, ‘that this rock was so idolised in this neighbourhood, and you may imagine my astonishment when I found all Penzance in an uproar. I was to be transported at least; the newspapers have traduced me, and made me worse than a murderer, and the base falsehoods in them are more than wicked’.

Nevertheless, whether bowing to pressure from the Admiralty or out of genuine contrition, he vowed to put ‘the bauble in its place again and hope[d] to get as much credit as I have anger for throwing it down’. He received the support of an eminent Cornish engineer and politician, Davies Gilbert of Tredrea in St Erth, who persuaded the Admiralty to provide all the equipment necessary for the attempt free of charge and pledged £25 towards the cost of labour and other expenses which Goldsmith, a man of relatively little wealth, was expected to meet.

After months of preparation, work began on October 29th, 1824, and the Royal Cornwall Gazette reported that crowds of people watched the rock being carefully hoisted back up the cliff with the assistance of cranes, winches, and sheer muscle power. At around 4.20pm on November 2nd a great cheer went up as the stone finally rested in its former position and was seen to rock. A correspondent was moved to remark that ‘it is but justice to Lieutenant Goldsmith to say that he evinced the greatest care and intrepidity in this difficult and dangerous undertaking, tho’ nothing can excuse his first act’.

Goldsmith remained in the Navy but was never promoted, and was dogged by his escapade until his final days. A receipt displayed in The Logan Rock public house in Treen shows that the Lieutenant only finished paying off his share of the £130.8s.6d restoration cost (around £18,000 today), and the accrued interest, shortly before he died in 1841 at sea on the HMS Megaera off St Thomas in the West Indies.

To prevent a recurrence the rock was chained and padlocked; Treen, deprived of its monumental tourist attraction, was nicknamed Goldsmith’s Deserted Village. Even when the rock was eventually freed, it was not as mobile as it once was — and if the early 19th century pictures are to be believed, its appearance is nothing like as striking.

That said, local historian Craig Weatherhill asserts that a series of rhythmic heaves applied to the south-western corner of the rock will still get it moving, after which the motion can be kept going with the use of one hand. And evidence of Goldsmith’s escapades can still be seen: the anchor holes used to haul the logan are still visible in the surrounding rocks.

Treen’s logan was not the only Cornish rocking stone to attract the attention of the military. In 1650 during the English civil war, Shrubshall, a roundhead commander at Pendennis, had the logan at the top of Men-Amber rock near the hamlet of Nancegollan toppled, suspecting it to be either the meeting point for Royalists or the venue for pagan rites. It was never restored.

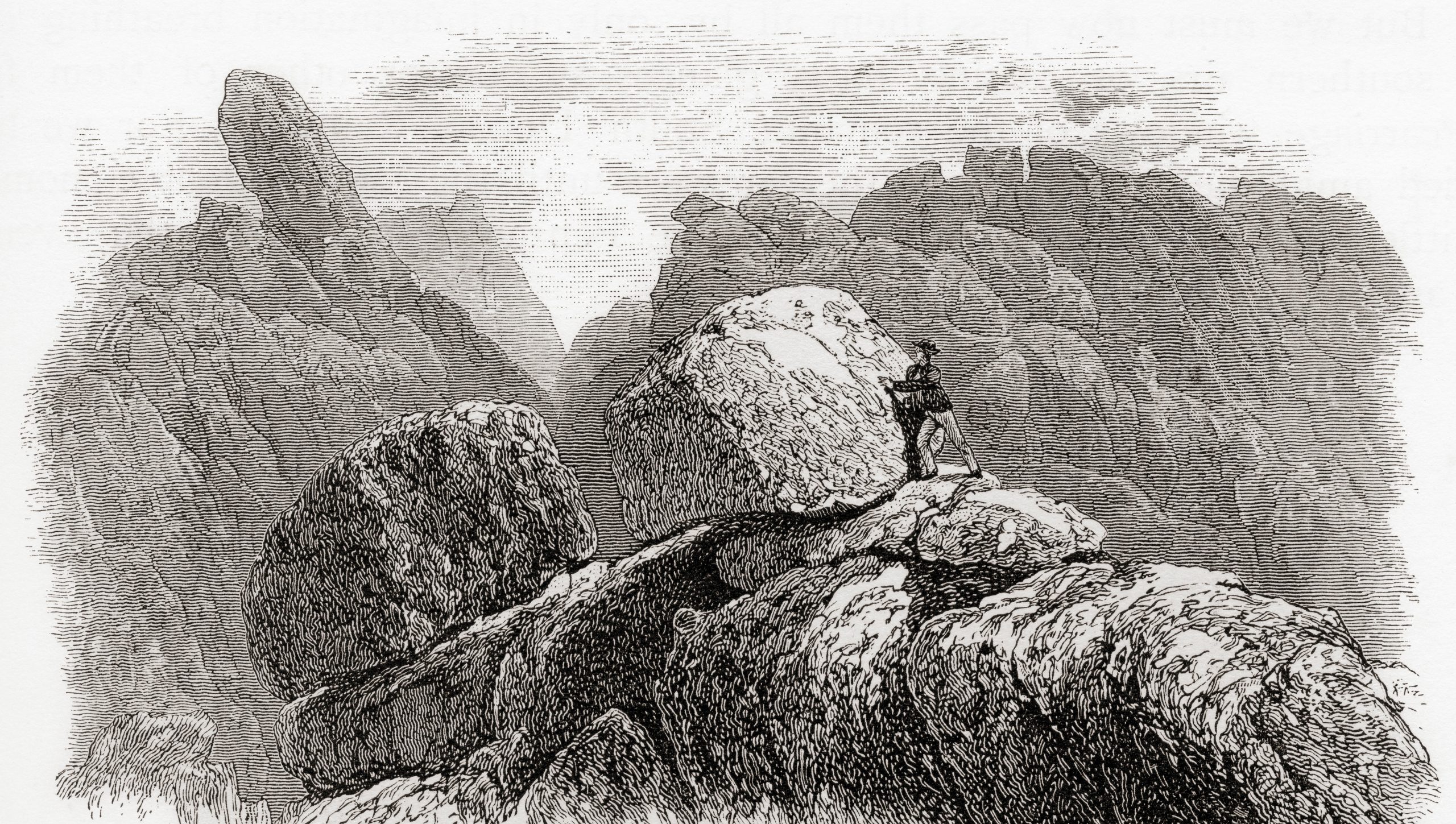

Of Cornwall’s other two significant logans, the one at Zennor, illustrated in 1858 a photograph entitled The Rocking Stone of Zennor, no longer rocks but, happily, the one on Bodmin Moor’s Louden Hill has so far evaded that fate.

Logan rocks are not confined to Cornwall. If you find one, do not do a Goldsmith — no matter how tempting it might be to earn yourself a perennial place in the history books.

Janine Stone: Creating spaces to show off your art, sculpture, car or and even wine collection

Flooring it: 10 ideas for beautiful carpet, wood, stone or ceramic floors

Country Life's interiors editor Giles Kime makes his selection of fine flooring for all types of different room.

Credit: New build in Berkshire by Janine Stone

A house that shows sometimes the best option is bulldoze your home and start again

An Arts-and-Crafts-inspired house in Berkshire demonstrates the possibilities of a new build, says Giles Kime.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.