Anything but bird-brained: The amazing wartime feats of carrier pigeons

‘Do pigeons have brains?’, the wartime Air Ministry once debated. BBC Security Correspondent Gordon Corera recounts the daring feats of these birds during times of conflict.

On July 26, 1943, a pigeon returned to its loft in Oxfordshire. However, this was no ordinary bird – it had been on a secret mission. Bred by a Barnsley fancier, its home was now a creeper-covered Victorian house on the village green in Tackley, Oxfordshire, with Mary Manningham-Buller. Her husband, an MP who would eventually be Attorney General, was away in London (their daughter, Eliza, would, decades later, become head of MI5).

A motorbike roared up the village green to collect the pigeon, which had a canister attached to its leg. Inside was a message that had been penned by an undercover agent a few days earlier in France. This was the pigeon’s third return from behind enemy lines in France – enough to win it the Dickin Medal, awarded to animals for bravery.

Manningham-Buller’s birds, which returned from France 20 times, were particularly valued as some brought back news relevant to an urgent priority for British intelligence: the hunt for Germany’s most advanced weapons. Her pigeons may have been especially successful, but Manningham-Buller’s role wasn’t unique.

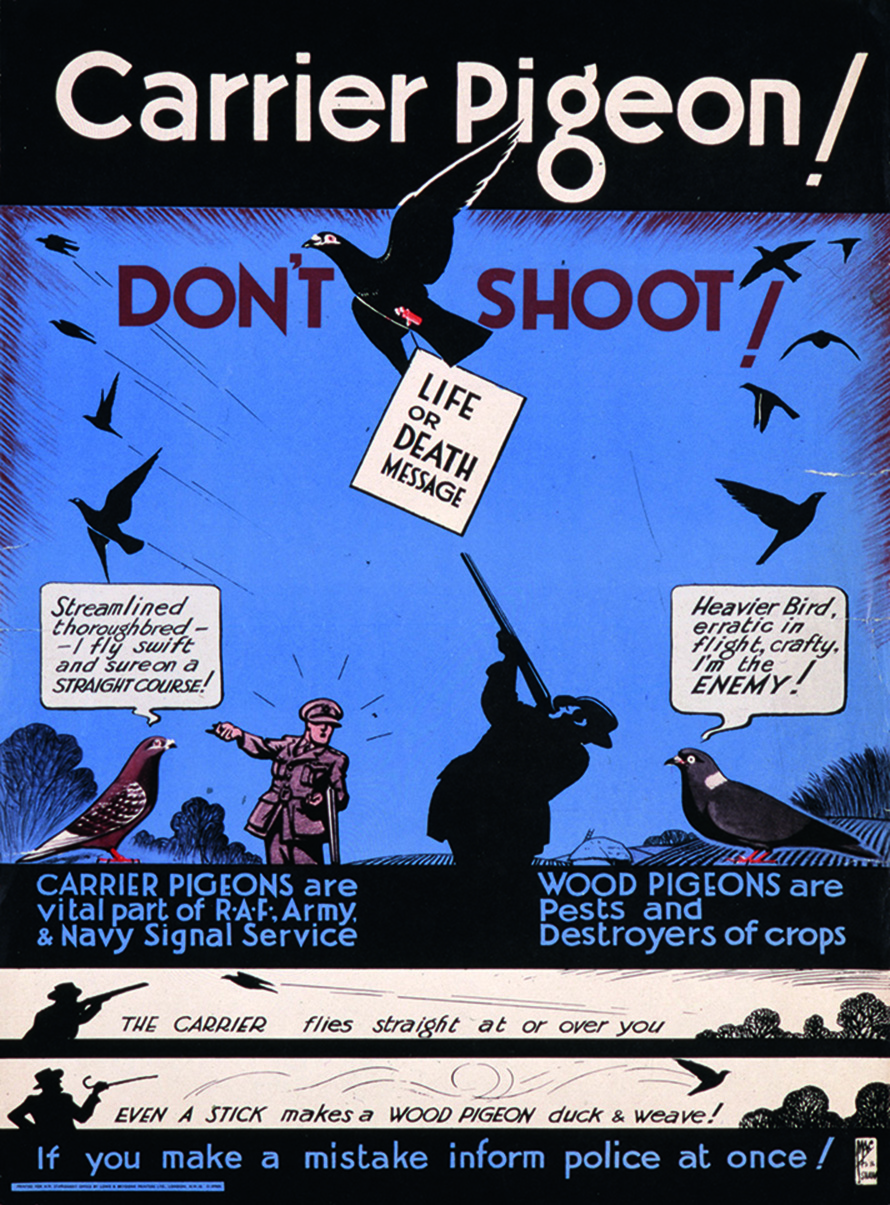

Thousands of people from every walk of life helped breed or keep pigeons as part of the war effort, their lofts scattered across gardens in countryside and city alike, all awaiting a potential arrival with a message that could make the difference between life and death.

Pigeons have a long pedigree in wartime – their ability to be released in any location and find their way back home carrying a message had long been recognised as a valuable communications tool. However, in the Second World War, they came into their own.

The first success was in early October 1940, when Philip Schneidau – Agent Felix – was parachuted into France, carrying with him a pair of pigeons supplied by a fancier vetted by MI5. Schneidau was advised to cut the toes off a pair of socks and stuff the pigeons into them, with their heads peeping out. On the sixth attempt, he finally parachuted into France.

Ten days later, a Lysander plane that was supposed to pick him up didn’t appear. Schneidau encoded a message and attached it to the leg of one of the pigeons, releasing the bird from Fontainebleau at 8.20am on Sunday. By 3pm the same day, the pigeon arrived in Kenley, just south of London, with news of his plight.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As well as being used by undercover agents, birds were carried by RAF flights in case they crashed. At 11.30am on October 10, 1940, the same month as Agent Felix set off, a pigeon called Royal Blue arrived back at the Royal Family’s loft in Sandringham. The bird was owned by the King himself and had been released in Holland at 7.20am that morning, carrying details of a crew that had made a forced landing on the Continent. It, like the pigeon that made it to Kenley, was one of the select few to win the Dickin Medal.

Recognising pigeons for bravery wasn’t without controversy. At one point, there was a surreal debate within the wartime Air Ministry about whether they should be entitled to awards in the same way as dogs. ‘I don’t want to be unduly hard on the pigeon,’ one officer began, before going on to say it was unfair on guard dogs to compare the two as the canines had been taught to use their brains, whereas pigeons were just following a homing instinct and so could not be considered brave. ‘Do pigeons have brains… please comment,’ he wrote in a memo.

The pigeon supremo in the Air Ministry responded with a long missive. Two might have the same training, but one would push itself harder to make it home—in other words, it wasn’t blind instinct, but ‘voluntary determination’. The pigeon also had to overcome its fear of drowning and take huge risks despite being more naturally timid and nervous than a dog, it was argued.

As war ended, life for pigeon fanciers began to return to normal. In the House of Commons in February 1948, Reginald Manningham-Buller MP raised the subject of pigeons, no doubt thanks to his wife’s experience. He questioned the Secretary of State for Air about a suggestion there would be no future role for the birds in war. The Secretary of State promised to look into the issue, but the days of pigeons as a vital wartime communications tool were passing. The birds – and their owners – had played their part.

‘Secret Pigeon Service’ by Gordon Corera will be published by William Collins on February 22 (£20)

15 fascinating things about animal actors, from dogs and cockroaches to the penguin who was fired out of a cannon

Animal ‘actors’ are often remembered long after their human co-stars. Flora Watkins meets people who’ve worked with ravens, stags, dogs,

Beautiful bird baths that will send your heart all of a flutter

Many birds, from wrens to pigeons and even gulls, will come to the bird bath, either to wash down dusty

Beginner's guide to clay pigeon shooting

We outline our tips for new shots hoping to become top gun.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.