The comeback of tweed

Tweed is making a comeback – Clive Aslet investigates

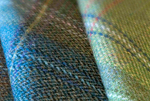

Tweed began life as a mistake. A bolt of cloth came down to a London tailor marked ‘tweel'-that is, twill, a kind of weave-and he misread it as tweed, that being the name of a Scottish river. It was, in marketing terms, an error of genius. Tweel suggests nothing, unless to garment manufacturers. Tweed evokes glorious scenery, leaping salmon and Sir Walter Scott.

Tweed emerged just as Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were popularising the High-lands. Rough, weatherproof cloth appealed to men who spent most of their days fishing and stalking or knocking about in poorly heated country houses. In 1924, George Mallory tried to climb Everest in a tweed Norfolk jacket-if he perished in the attempt, nobody blamed his clothes.

Since then, tweed's supremacy as the outdoor material of choice has been challenged. It suffered from the general post-Second World War collapse of the British textile industry. Clever products such as Gore-Tex appeared, keeping the rain out and allowing shooters a freer swing.

The Italians reproduced the tweed look-peaty colours, contrasting overchecks-in lightweight and positively lubricious materials, designed for an urban clientele. Fifteen years ago, Country Life seduced the dandies of Britain with its own tweed, woven by Hunters of Brora, but, alas, not even that association could stop the mill from closing in 2000.

But don't think that tweed is dead. On the contrary, the cloth's sporting supporters are coming back to it, convinced that this natural fabric has qualities that manmade materials can't beat. Weavers are also creating new tweeds, to be used in new ways. To what might be the consternation of the traditionally tweedy set, the fabric is in danger of becoming hip.

In 1995, when the tweed mill Johnston's of Elgin was looking forward to its 200th anniversary, it brought out a book called Scottish Estate Tweeds. There they all were: the green, the grey and the ginger, the bright window panes and the heathery blurs, evocative of hillsides, shooting lunches and county shows. Now, however, the book would be far from complete.

Estate initiatives

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Estate owners are favouring tweed to such an extent that some are designing their own. ‘It was a bit of fun, really,' says Mark Horton of Carsaig, on Mull. But serious fun all the same. Noticing that the colours of the hills in autumn-orangey light brown, as the heather died away-he commissioned a local weaver to make samples; these were duly taken out onto the hill to see which matched. As a camouflage, the result is well nigh perfect: ‘After 100 yards, I completely disappear into the landscape,' says Mr Horton.

Tweed may get wet on those rare occasions in Scotland when the weather is less than perfect, but, being a natural material, it allows the person inside it to dry out again, rather than feeling as though wrapped in clingfilm. Although, as Mr Horton comments: ‘It's amazing how long heavy tweeds will keep you dry.'

You could hardly have a more authoritative source on estate tweeds than Edward Bromet of the Moorland Association. ‘We all have them,' he comments. There is a pride in the uniform among the keepers. ‘Even on a roasting-hot day, they will keep on their three-piece suits and tweed caps.' On his own grouse moors in Yorkshire, they have recently instituted the economy of providing new tweeds only every other year. Worn not just on shooting days, but throughout the year, they get a lot of wear; with the season starting on August 12, tweeds on the grouse moor tend to be thin.

‘They would be fainting in the beating line if they wore thick tweeds,' he observes. For stalkers in particular, tweed has the advantage of being silent. ‘Velcro can be quite noisy on the hill,' observes Miriam Campbell, who has noticed a return to traditional fabrics. With her brother James and sister Catriona, she runs Campbell of Beauly, which has been tailoring tweeds outside Inverness since 1858. Although Hunters, as a local mill, was a particular loss to the Campbells, they have noticed that other companies have been quick to copy their striking patterns; the new centre of tweed production is around Hawick in the Borders.

The ‘saviour' of Harris

‘It isn't so much a cloth, it's a club,' observes Brian Haggas, whose family has been in textiles since 1715. He saw a jacket made from Harris tweed and liked it so much that, in December 2006, he bought Kenneth Mackenzie Ltd, responsible for nearly all Harris tweed's output. Based in Keighley, Mr Haggas could not be mistaken for anything other than a Yorkshireman: ‘I say what I think, always have.'

And what he thought, at the age of 75, was that there had to be change. Previously, weavers worked to an enormous number of patterns-said to be as many as 8,000. ‘I told them I would cut this down to four. "Four thousand?" they asked. "No," I said. "Four."' There was, he remembers with relish, ‘a riot on the islands. A woman came to see me to say it was the ruination of Harris tweed. She was livid. I received signed deputations from 600 people. The minister in the pulpit called me "that vile serpent within". Marvellous stuff.'

Mr Haggas sold off the existing stock; new stock, woven to the four chosen patterns, has been made up into 75,000 jackets, which are now sold throughout Europe, the USA and Canada. ‘Everywhere you go, people know Harris tweed. They have a fondness for it, a nostalgia-because they see it as yesterday's fabric.' A manufacturer turned retailer, he is now out to convince the world that it's tomorrow's fabric, by selling a range of ready-to-wear jackets in the famous four patterns, their understated colours being as natural and complex as the machair itself.

Cutting a dash

Understatement is never a word that could be applied to Dashing Tweeds, the cynosure of all eyes in Notting Hill. Some of its patterns, designed by the photographer Guy Hills and woven by Kirsty McDougall, are enough to make a laird's eyeballs burst from their sockets and bounce round the glen. Spectacular in vibrancy and colour, the sporting range outdoes the Victorian taste for loud effects, and, although they could probably be seen from the Moon, would undoubtedly, in Mr Hills's words, ‘bring panache' to any outdoor occasion.

A family tradition

The front room of Iain Macleod's cottage on the northern tip of the Isle of Lewis, outside the village of Ness, is a world away from NW1. Ian's father Donald, universally known as Zebo, would weave between spells working on or around North Sea oil rigs. It was not a craft that Ian expected to follow, his own career having begun as a scriptwriter and film-maker. But when, two years ago, the opportunity came to buy Breanish Tweed from Ian Sutherland, an innovative Harris weaver, it was too good to miss: ‘The product was great; it would have been a real shame to let it die.'

Building on the beautiful patterns already developed, Mr Macleod has introduced more luxurious yarns, such as geelong lambswool, vicuña, alpaca and silk. This enables him to sell what, in tweed terms, is a gossamer-thin 9oz weight, as well as a double Shetland, which is Teflon-coated for waterproofing. And there, besides bolts of autumnal herringbone is a pair of high-heeled shoes in a dramatic red-and-white check with green overcheck, woven for Manolo Blahnik.

One of Breanish's star weavers is, naturally, Zebo, now retired from the North Sea. And in another shed-one, as she proudly points out, with carpet-is Karin Slater, who, having studied creative writing in Wales, has now returned to the place where she grew up. ‘I must be the youngest weaver by far,' she laughs. Despite the carpet, the shed could hardly be called warm on a Hebridean December morning.

However, that doesn't worry her. Her old-fashioned Hattersley loom is worked by foot pedal: the effect on the body temperature is like cycling. The glorious cast-iron machine weaves only to the traditional single width, which is an advantage for a small and specialist company such as Breanish, because it allows cloth to be made in short runs.

Tweed in all forms

Tweed need not be limited to garments; Anta, established by Annie Stewart on the East Coast of Scotland, shows how well it can look as a throw, as a carpet or as a carpet bag. There is a joy in the patterns, which seems immediately to teleport you to a Scottish castle or country house-much like the one that Mrs Stewart and her architect husband, Lachie, have restored.

Of course, this is the key to tweed's secret: it's the most evocative material in the world. It can verge on the mystical. ‘Our intention is that Ardalanish be a place of conversation, of interpretation, of stories, of creativity and of inspiration.' This quote comes from the website of an organic weaving mill (which is also a farm) that has recently been established on Mull, and is canny enough to sell cloth ot the Jigsaw fshion chain. Stories, creativity, inspiration-yes, they're all part of tweed. It's terribly hard wearing, too.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.