‘I cannot bring myself to believe that Emily Brontë would be turning over in her grave at the idea of Jacob Elordi tightening breathless Barbie’s corset’: In defence of radical adaptations

A trailer for the upcoming adaptation of 'Wuthering Heights' has left half of Britain clutching their pearls. What's the fuss, questions Laura Kay, who argues in defence of radical adaptations of classic literature.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Wuthering Heights but make it Brat. This sentence would have made no sense even 18 months ago, yet here we are, in the year 2025, watching a trailer for an Emerald Fennell adaptation with an original score and soundtrack by Charli XCX. Anything can happen.

Like anyone who is chronically online, halfway through watching Margot Robbie, our newest Catherine Earnshaw from Yorkshire, speaking with an RP accent, I scrolled down to the comments. They did not disappoint.

Among the people screaming their favourite Wuthering Heights lines into the void (‘You said I killed you-haunt me, then… only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you!’) there were many variations of the following:

‘...hear that? That was the breathless gasp of the corpse of the author having a stake nailed through her heart.’

I get it. Really, I do. Literature imprints upon my heart as much as the next person. I am an author after all, and a romantic one at that. I am prone to attaching myself to lines from poetry or prose in ways that sometimes make me believe they are speaking directly to me. I have even been tempted to tattoo them onto my skin, a permanent etching as if that might mean more, that I might be able to absorb them entirely. And yet, I cannot bring myself to really believe that Emily Brontë, an exceptional woman who took huge, beautiful risks in her work, would really be turning over in her grave at the very idea of Jacob Elordi tightening breathless Barbie’s corset.

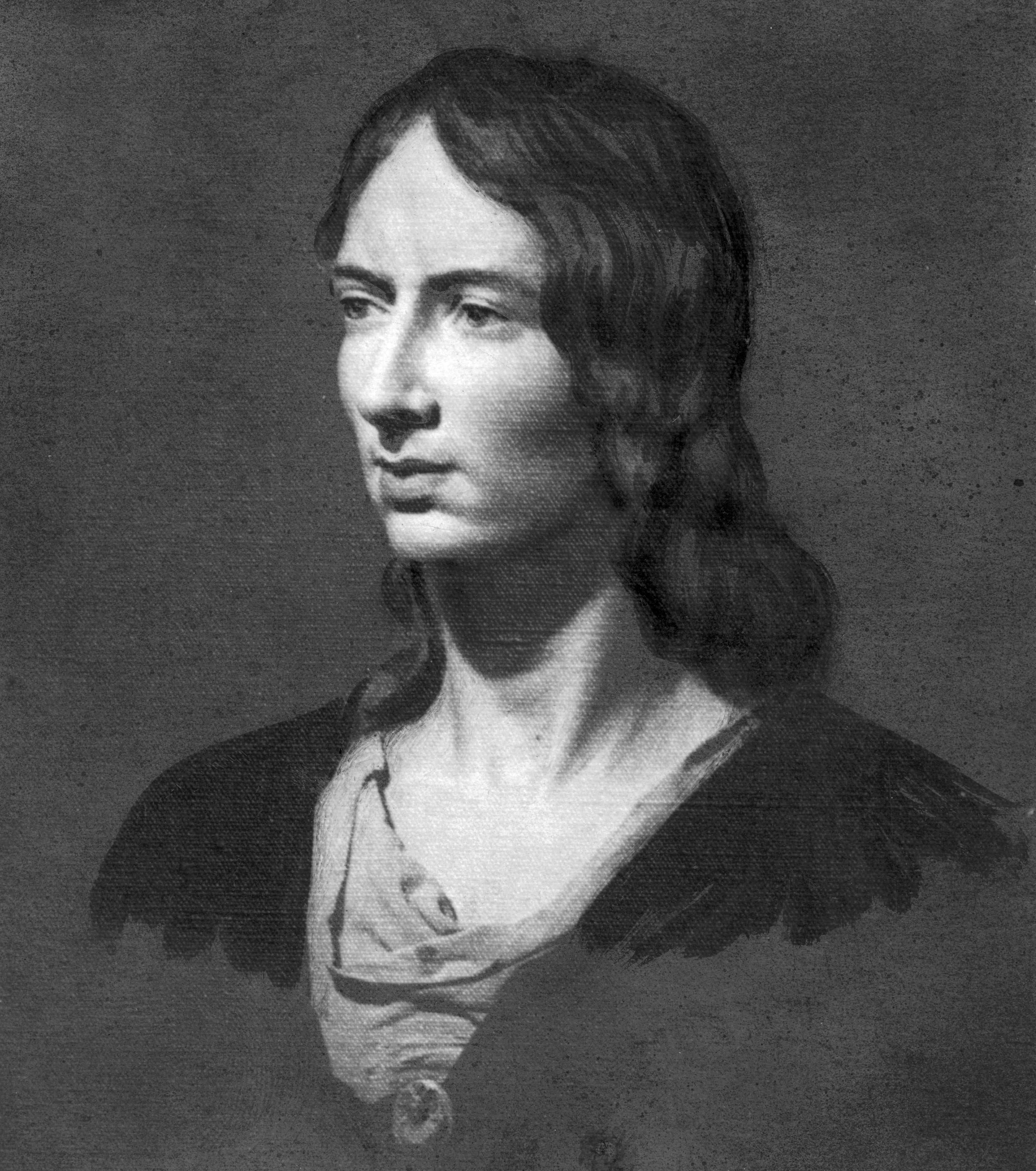

Emily Brontë (1818-1848) was the fifth of six Brontë siblings, four of whom survived into adulthood.

While Brontë’s original text does not open with necrophile nuns and horse reigns bondage as Fennell’s adaptation does, according to test audiences who described it as ‘aggressively provocative and tonally abrasive’, the two works do share that shock factor.

Wuthering Heights, while revered now as an untouchable classic, outraged readers when it was first published in 1847 under the pen name Ellis Bell. According to historian Juliet Gardiner, readers were ‘bewildered and appalled’ by its vivid sexual imagery with early critics describing it as ‘utterly shocking and thoroughly contemptible’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

I do not think that any of us are able to accurately guess what Brontë’s reaction might be to any of the many adaptations of her work. However, I do wonder whether she might have been just a little excited by what contemporary female artists are now making of her work and what women are now allowed to conceive and create. Perhaps she might even be delighted that her story was still being consumed by new audiences, generation after generation falling for new Heathcliffs and new Cathys while the moors remain the same — wild, barren, hostile places within which dark and all-consuming love stories still take place.

I cannot bring myself to feel too concerned that younger audiences may see this film and consider it the definitive Wuthering Heights (although I highly doubt that will be the case). The rise of ‘Booktok’ and organic social media trends, especially around romance novels, continues to propel popular fiction at rates book publishers and marketers can only dream of. Feminist, modern adaptations of folklore and mythology, in particular, have been phenomenally popular, with retellings such as Madeline Miller’s Circe and Bolu Babalola’s Love in Colour introducing teenagers to stories they may never have encountered, far less have recognised themselves within.

Watching a trailer on Instagram might be the first place a teenager encounters Wuthering Heights, maybe even leading them to find the original. I watched Baz Luhrmann's Romeo and Juliet as a teenager and while I understand that Shakespeare’s version was not set in the 1990s and the Montagues did not wear their hair in boyband curtains and pair it with Hawaiian shirts, I had infinitely more fun with that than I did with the original text and I’m pretty sure I got the gist of it (don’t ever test me). I think perhaps the ‘stylised depravity’ of Fennell’s Wuthering Heights may have made an even greater impression.

I am aware that aside from the delightful and squeamish disgustingness of it all, there is legitimate criticism for this adaptation casting a white actor in Heathcliff’s role, who is, according to the original, supposed to be ‘dark skinned’, ‘foreign’ and ‘gypsy like’ and not look like Jacob Elordi — which is to say, like an Australian Elvis. This, along with the more general criticism for the film, was addressed by the casting director Kharmel Cochrane who, when discussing the fact that she has seen comments saying she ‘should be shot’ (we, as a society, have lost it) said: ‘(we) really don’t need to be accurate. It’s just a book. That is not based on real life. It’s all art.’

Whether you agree with her or not on her casting choices, this much is true: it is all art. When Brontë wrote Wuthering Heights, I would be surprised if she viewed it as a sacred text designed to be preserved forever. When an artist puts work out into the world they release it. It no longer belongs to them; not really. You cannot manage the way people hear your words, view your images or listen to your songs. You cannot control their emotions or correct them. You create, you perfect — and then you let it go to take on new meaning. If you’re lucky it resonates not just with one person, but with many over generations; perhaps even a century and a half later you will still inspire people to make something new. And maybe you wouldn’t like it, but it’s all art, and nothing is sacred.

May we always be surprised, shocked, appalled and bewildered by art. I hope we’re having this conversation again in another 100 years and another 100 after that. Wuthering Heights is ours, Fennell’s and of course, Charli XCX’s to do with what we please and if some people don’t like it, the original is waiting untouched for them to return to, anytime they like.

Laura Kay is a writer living in London. Her journalism and personal essays have been published in The Guardian, Diva Magazine and Stylist among others. Her debut novel, The Split, was published by Quercus in March 2021. She has since published three further novels in the UK, the USA and other territories.