'Never willing to pardon where I had a power to revenge’: The history of the duelling class

Settling a dispute with swords, pistols and, if legend is to be believed, sausages and guitars, has long been a matter of honour even among modern-day rock stars, discovers John F. Mueller.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You should absolutely not attempt this at home. Duelling comes with a roughly 50% chance of dying, the risk of bleeding profusely and a very early start. Little wonder it has been illegal since at least 1215, when the Fourth Lateran Council in Rome, Italy, outlawed it. Since then, the practice has been forbidden again and again by successive institutions in dozens of countries. However, in spite of this, duels have continued to be fought, referred to numerous times across art and literature.

Samuel Johnson, for example, believed that ‘a man may shoot the man who invades his character, as he may shoot him who attempts to break into his house’. In a world before credit checks and LinkedIn profiles, character and reputation were important assets to individuals — so important that they could influence how much money you could borrow or whom you would be permitted to marry. Those with social capital —principally the nobility, but also the professional classes as time went on — could lose face if they were ‘slighted’ by being disrespected or diminished in the eyes of their peers: a reputation was a tangible asset worth defending.

Originally, fighting between so-called ‘injured’ parties was regulated by the ruling court and approved by the monarch. It took place between nobles and could have a deadly outcome. However, the duel as we now know it from romantic literature and swashbuckling films originated in 16th-century Italy and France. These altercations required swords or pistols to be ready at dawn and a picturesque, but clandestine location. The whole thing was considered rather barbaric even then, but a misguided chivalric sense of honour flourished among (especially young and probably romantically inclined) men.

Hanged in June 1612 for duelling, Robert Creighton, Lord Sanquhar, confessed at his trial that he ‘was never willing to put up a wrong, where upon terms of honour I might right myself, nor never willing to pardon where I had a power to revenge’. One of Alexandre Dumas’s musketeers could not have put it better. What makes a duel a duel, as opposed to a straightforward fight? The lines are somewhat blurred, especially as the romantic notion of a duel often suits a narrative better when it is recounted after the fact. The main difference is the formality and perceived sense of honour that exists between parties: in some form or another, Person A needs to have done something to diminish Person B’s honour (or that of their family or partner). Person B must be so upset about this that they require something be done about it, unless the statement is retracted by Person A. This is for the ‘seconds’ of B to negotiate; they aim to prevent violence through discussion. If, however, A refuses to make amends, B’s seconds can challenge A to a duel. Person A may choose the weapons, which, since about the 18th century, have been swords or pistols.

A post shared by Latribudelcine (@latribudelcine)

A photo posted by on

To add to the drama, they all meet at dawn on a subsequent day. The seconds of both parties agree a protocol for the situation: how many steps to take, how many shots are to be fired, at what point ‘satisfaction’ will occur (the drawing of first blood, the firing of the shots, the death of a combatant) and how the body, if one results, is to be removed.There have been many variations to this scenario, some even codified.

In 1777, a group of Irish gentlemen wrote down duelling practices in the Code Duello, a publication considered the most bloody of guidelines on the subject. It contained 26 rules outlining all aspects of duelling, from the time of day when challenges could be received to the number of shots or wounds required to satisfy honour. An American version appeared in 1838, written by past South Carolina governor John Lyde Wilson.

That the American Founding Father Alexander Hamilton called his political opponent Aaron Burr, a ‘profligate, a voluptuary in the extreme’ and that Burr, in turn, published documents of Hamilton’s not intended for the public, will tell us something about their relationship to each other. When sometime vice president Burr was seeking re-election, information was leaked that Hamilton had expressed a ‘despicable opinion’ of Burr at a dinner. What exactly he said has not been recorded for posterity, but it was enough for the two men to meet on July 11, 1804, for a duel. Burr wounded Hamilton, who died from his injuries: Burr had not only committed a murder, he had finished his own political career.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In 1843, after getting into a row over a game of billiards in a Paris bar, two now notorious Frenchmen named Melfant and Lenfant supposedly challenged each other to a duel. Their weapons? The very balls they had used for their game. They reputedly drew straws to determine the first thrown and, standing 12 paces apart, intended to lob the billiard balls at each other. This may sound bizarre, or even funny, but the first ball — a red one thrown by Melfant — killed Lenfant by hitting him on the head. Melfant was promptly carried off, arrested and convicted for manslaughter.

Duels on the screen and stage

In the 1975 film Royal Flash, based on the ‘Flashman’ novels, audiences are treated to a Mensur, an academic type of fencing duel practised by the elite student fraternities in German-speaking countries

Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin is a beautifully sad version of Pushkin’s book of the same name, in which the eponymous hero meets a tragic end in spite of winning his duel

Duels feature heavily in the musical Hamilton, including in a number dedicated to the technicalities of duelling

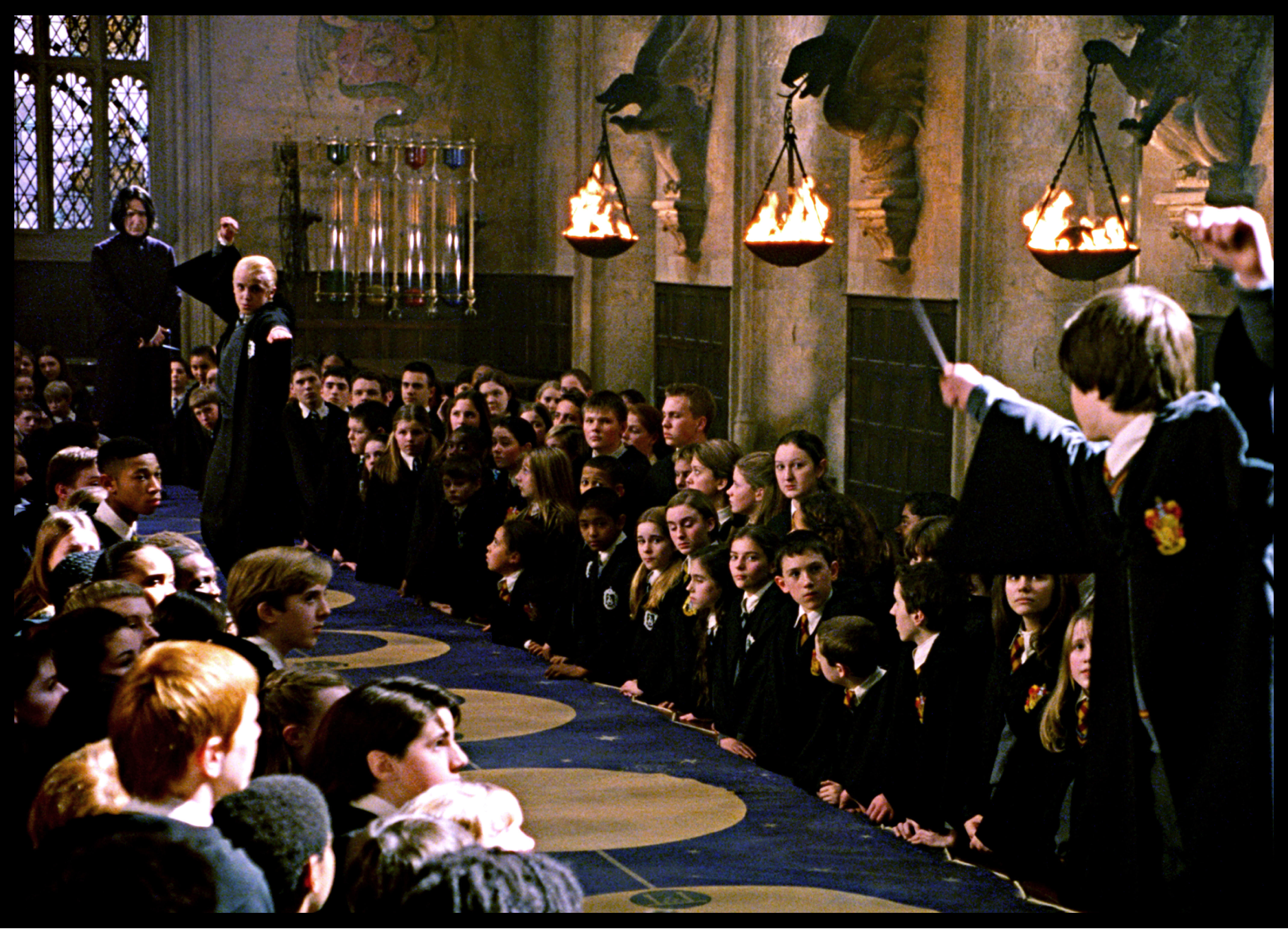

In the second ‘Harry Potter’ book and its film adaptation, Hogwarts students are taught how to defend themselves by means of a duel (although we cannot call it a duel if its purpose is defence, strictly speaking)

The 1977 Ridley Scott film The Duel-lists is a fantastic swashbuckling tale

The first season of the Netflix series Bridgerton features a duel between Daphne's brother and her potential suitor when the former fears the loss of her honour

Early in Otto von Bismarck’s political career, before he became Chancellor of the German Empire, he was prime minister of Prussia. In 1865, his fiscal plans for the Prussian navy had been rejected in parliament and the progressive politician and scientist Rudolf Virchow had made some comments at the future chancellor’s expense. Von Bismarck sent seconds to Virchow’s laboratory to challenge him to a duel. The most reported story is that the learned politician accepted and chose two pork sausages as the weapons. One was infected with a deadly parasite he was researching, the other wholesome. Whoever chose the healthy sausage to eat would win the challenge. However, there are possibly more credible reports that record that Virchow apologised publicly and the matter was settled.

Newspapers considered the affair a ‘barbarous act’, even in the early 19th century. It was later said that Hamilton had deloped, or shot to miss, which was considered the acceptable stance to take. His opponent, on the other hand, was alleged to have acted out of grim defiance and carried out his intention to kill.

No sooner had the concept of duelling flourished and spread across the western world than its decline began in Britain. The rising commercial class, with its evangelical-leaning Christian ideals, considered duelling an elaborate, barbaric practice unworthy of high-minded and civilised men. ‘A quarrel pursued for its own sake’ was hardly turning the other cheek. The 1st Duke of Wellington and his rival, the charmingly charismatic Earl of Winchilsea, fought one of the last duels in England over Roman Catholic emancipation. The Duke (perhaps deliberately) missed and the Earl discharged his pistol into the sky, thus resolving the matter without bloodshed. However, the British public were outraged by the spectacle: duels had finally fallen from favour. Although duelling continued on the Continent and in the Americas for a while longer, the last known one on English soil was fought by two Frenchmen in 1852.

Or, at least, the last one fought with deadly weapons: in his biography, the actor Sir John Hurt is reported describing a duel of sorts that George Harrison and Eric Clapton fought over the model Pattie Boyd, who inspired several of Harrison’s songs, as well as Clapton’s Layla.

George Harrison and Eric Clapton had a very modern kind of duel.

Boyd was married to Harrison at the time of the altercation, but Clapton had fallen madly in love with her, leading to a complicated love triangle. Things came to a head at Harrison’s Oxfordshire home, where the two men met. During a jam session, they let out their fury at the situation and passion for Boyd through their guitars. Bizarrely, as one witness of the altercation commented, this was an intensely English confrontation, in which all emotions were suppressed and channelled into creativity. Clapton would go on to marry Miss Boyd after her divorce from Harrison—but sadly for us, not as a result of the duel.

This feature originally appeared in the June 18, 2025, issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe