Inside the restored Brighton Pavilion: ‘It’s hard to imagine a more perfect time to visit this extraordinary Regency creation’

After a major restoration of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, it is possible once again to enjoy one of the interiors created to satisfy the opulent tastes of the Prince Regent. John Goodall takes an in-depth look at the Saloon, with photographs by Paul Highnam.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

More than any other single building, the Royal Pavilion in Brighton exemplifies the spirit of the Regency. In its opulence, it expresses the wealth of a kingdom that knew itself not merely to be rich, but the richest in the world; in its exoticism, one that was enjoying the fruits of global power; and, in its triumphalism, one that was still revelling in victory over Napoleon after a quarter of a century of gruelling war.

Flavouring the whole is the hedonism of the Regent himself, a man who, in more expansive moments of vanity and despite latterly growing so corpulent that he could not walk up and down the stairs of his creation with ease, saw himself as the source of Britain’s success.

Brighton and Hove City Council has been maintaining and restoring the Pavilion over many years. In 2017, under the direction of the Keeper of the Royal Pavilion, David Beevers, this work passed another landmark with the restoration of the Saloon as decorated by Robert Jones in 1823.

This exemplary project has been in the planning for about 15 years, involving some remarkable detective work and an enormous breadth of expertise.

The result offers a fresh and compelling insight into the character of this astonishing building as George IV knew it. This ground-floor room formed the central element of the original Pavilion begun in 1787 by the architect Henry Holland. At that time, it was a relatively conventional neo-Classical ‘drawing room’, although circular in plan and with a low dome.

A drawing by Rowlandson shows this original interior with walls painted by Biagio Rebecca and the door to the room beyond curiously contrived within a recess at one side of the interior. Externally, it projected as a bow with windows opening onto the garden.

Here, the Prince of Wales (Regent from 1811) would meet his assembled guests for dinner in the evening. He expected the men to stand in anticipation of his arrival, but the women could sit. As he entered, they would rise to their feet and he walked through to dinner with the most important on his arm.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It was also a setting for dances, when the carpet would be stripped away and the bare boards of the dancing area chalked with imagery. Such decoration would have been immediately spoilt, but it served the practical role of preventing the dancers’ shoes from slipping on the wood.

In 1802, the room was reordered by the decorators Frederick and John Crace for the Prince, in a Chinese style. As such, it was the first interior in the Pavilion to adopt an exotic idiom. As part of this work, painted Chinese wallpaper on a blue ground was applied to the walls and the dome was decorated to look like the sky.

It was at that time that the room was first called the ‘Saloon’. The term had been commonly applied to formal reception rooms in English houses during the 18th century, but, by this date, it was relatively outdated. Perhaps the choice of denomination underlines the Prince’s desire to emulate French forms and fashions (of which the name Pavilion was likewise a borrowing, referring to suburban houses in the environs of Paris).

Buoyed up by Britain’s triumph over Napoleon, Crace’s interior was further adapted in 1815, when the Pavilion was externally recast by John Nash in an Indian style. In Nash’s expanded plan, the Saloon was positioned beneath the central dome of the main elevation between the new Music Room and the Banqueting Room.

In 1817, as these changes were under way, the Prince summoned Frederick Crace and one of his subcontractors, Robert Jones, to discuss further alterations to the interiors.

Relatively little is known about Jones, largely because his common name makes it almost impossible to identify documentary references to him with certainty. All we do know is that he worked for the Duke of Northumberland and, from the evidence of his work at the Pavilion, that he was a consummate and assured interior designer. Indeed, latterly, he became known as the ‘chief artist of the palace’.

It was probably in the immediate aftermath of this visit in 1817 that Jones planned a complete revision of the Saloon interior. A watercolour of the room suggests that the whole scheme was briefly mocked up, presumably to judge its effect. Royal approval was evidently secured and the scheme executed with silk hangings and curtains, silvered wall decoration, a new fitted carpet woven at Axminster and a suite of furniture.

It was in an Indo-Chinese style, with a dragon supporting the central chandelier and a magnificent fireplace of white marble inset with silver and two figures in Chinese dress.

In 1820, the Prince Regent at last acceded to the throne as George IV and began to plot his transformation of Buckingham Palace, occupying Windsor Castle as his principal residence. Work to the redecoration of the Saloon at Brighton went ahead, nevertheless, and its interior was completed in 1823.

The new scheme looked much less frivolous than the earlier Pavilion interiors and, in stylistic terms, was redolent of the Empire style popularised in Paris from the 1790s by Percier and Fontaine, who were much patronised by Napoleon.

In this regard, the Saloon looks much more like George IV’s interiors at Windsor than the French Revival decoration executed on behalf of other rich patrons who indulged in such interiors during this period, notably those executed by Benjamin Wyatt for the King’s brother, the Duke of York at York House (now Lancaster House), the Duke of Wellington at Apsley House and the Duchess of Rutland (mistress of the Duke of York) at Belvoir Castle. These all assumed the forms of 18th-century French design, what Wyatt described as the ‘style of Louis XIV’.

That said, confusingly, the Saloon did make direct reference to Louis XIV in its unusual colour combination of red, gold and silver. The last is a great rarity in English interior decoration and the source for this particular palette of colours seems to be Versailles. It may be a further implied reference to the Sun King that the room incorporated the repeated motif of a sunflower, most prominently as the centrepiece of the carpet.

It is emblematic of the sheer opulence of the new interior that its surviving cabinets are carved both inside and out, mirrored internal surfaces reflecting ornamental joinery.

George IV returned to Brighton only twice for prolonged stays before his death in 1830. The Pavilion interiors now incorporated furnishings from the Prince Regent’s London residence, Carlton House, which was demolished in 1827. Napoleon’s writing desk was even installed in George IV’s bedroom, clear evidence of the King’s self-glorifying admiration for his vanquished opponent.

It is recorded that his brother, William IV, also visited the building and used the Saloon to inspect work by the sculptor Behnes. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert also came to the Pavilion, although the former seems to have felt that it offered little privacy and determined to sell it on. The Prince greatly admired the principal rooms, but, even so, the building was boarded up and much of the furniture and many of the fittings stripped out in 1847–48. Some, such as the Saloon’s chandelier, made their way to Windsor, but many more passed to Buckingham Palace, where they were incorporated in the wing being erected there by Edward Blore.

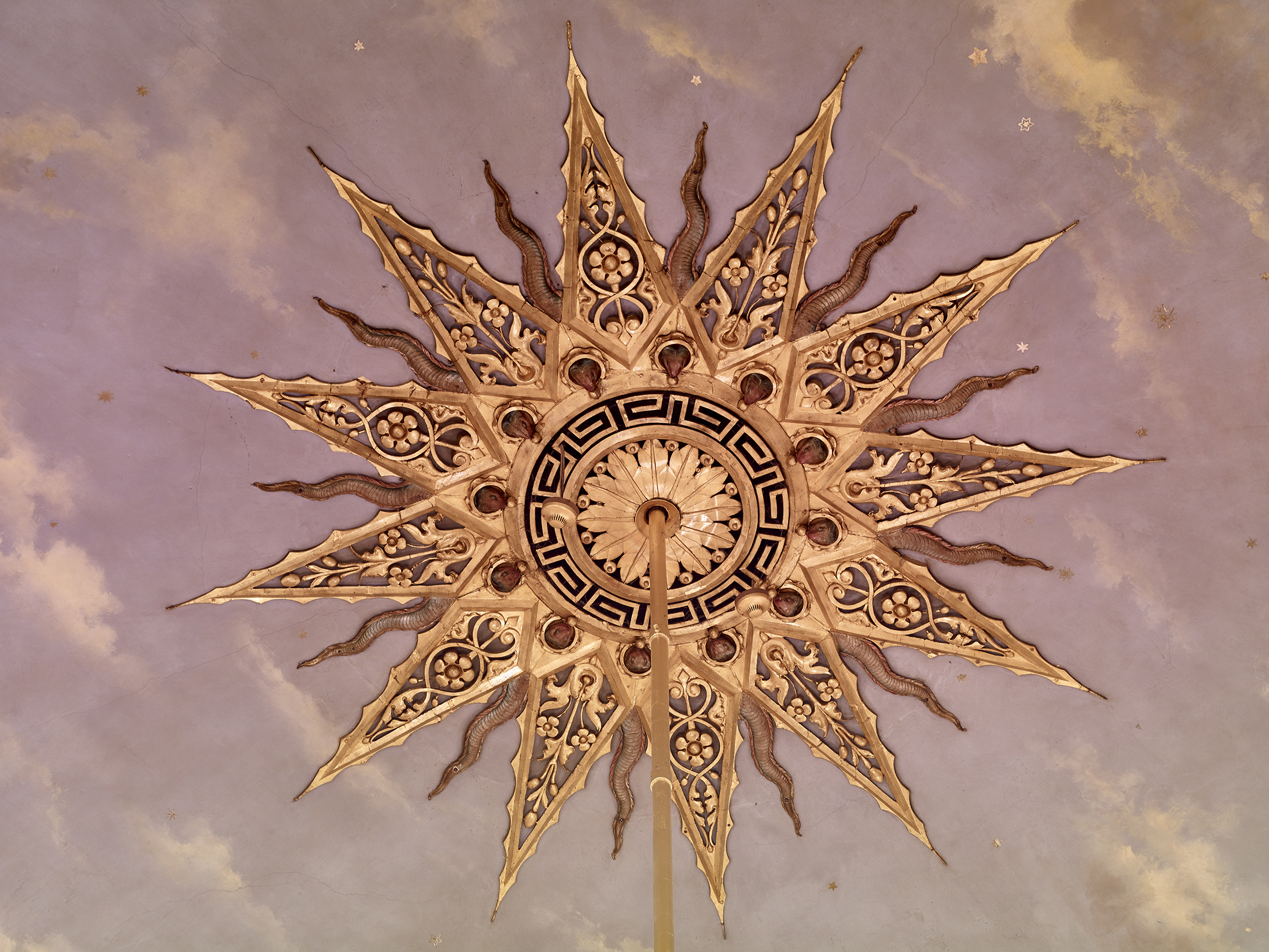

Famously, and in the teeth of opposition, the town council bought the pavilion in 1850. It not only saved it from demolition, but redecorated the interior of the Saloon. The present ceiling and its central star were probably created in 1864. Then, in 1896, J. G. Crace, another in the dynasty of London decorators, redecorated the room.

At the same time, Queen Victoria returned various fittings that had been removed from the Pavilion, including Saloon door frames Another of her gifts – probably – was a Chinese export wallpaper, mistakenly believed to have hung here. The doors and wallpaper were installed during restoration work in 1930s, together with some of Jones’s original pilasters given by George V.

In 2002, water damage in the Saloon revealed traces of the Jones decoration. A relatively modest scheme to restore this suddenly grew much more ambitious following the discovery of the pattern for the original silk used in the interior by historic textile consultant Annabel Westman. Using a combination of evidence, including photo-graphs, fabric fragments and a sample from a merchant’s book, she managed to identify what the supplier to the room in 1823 described as ‘His Majesty’s Geranium and gold colour silk’. Its pattern is French in inspiration and has been rewoven for this restoration by Humphries Weaving .

Ian Block of A. T. Cronin Workshops made new curtains and hung the silk panels. The sumptuous trimmings were supplied by Brian Turner and Heritage Trimmings and braids and muslins by Context Weavers.

Meanwhile, a similar re-creation of the 1823 carpet was begun. According to the accounts of Jones, the original carpet cost the princely sum of £620. He personally oversaw the process of weaving on the loom ‘so as to make an unusual and intricate design capable of being rendered without error by the manufacturer’. Nevertheless, on removal in 1847, it was cut up for re-use in Buckingham Palace. George V returned some of the fragments in 1934. These, as well as some design drawings and historic views of the interior, have allowed the whole design to be pieced together by Anne Sowden, a permanent member of the Pavilion’s conservation team.

It took six months for carpet designer Jess Shaw, under the supervision of design director Gary Bridge, to digitise the design for a computer-operated loom at Axminster Carpets. The original carpet was woven with 26 different colours, but the replacement has refined the design to incorporate 12.

Using the evidence of exposed fragments of wall decoration, Mrs Sowden also worked on the problem of re-creating Jones’s covering of leaves and flowers. She perfected the polished pearl finish of the paper ground and the pattern, applied using laser-cut stencils.

The 12,000 motifs – each one taking about 16 minutes to form – have been applied over two years using platinum rather than silver, to deter tarnishing. Each is picked out with shadows in two shades of lilac.

No sooner has this landmark restoration come to fruition than another exciting project has come in prospect. As part of the ongoing restoration of Buckingham Palace, the wing built by Blore, which absorbed so many fragments of the Pavilion in the 1850s, is being temporarily stripped of its furnishings. The Queen is, therefore, loaning a large number of these back to the Pavilion for a period of three years. The loans should be installed in September this year.

When they are in place, the interiors will briefly appear more completely as they were known by George IV than at any time since the break-up of the interior in 1847. It is hard to imagine a more perfect time to visit this extraordinary Regency creation.

The Royal Pavilion in Brighton is open to the public throughout the year – see brightonmuseums.org.uk/royalpavilion for times and ticket prices.

Palaces on the sea: The story of the father of promenade piers

Eugenius Birch, father of the promenade pier, was born 200 years ago. Kathryn Ferry considers the life and remarkable legacy

12 wonderful things to do in 2018 which showcase the very best of Britain

If you're looking to make more of life in Britain over the next 12 months, Country Life's suggestions are here

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.