The story of the red telephone box, one of the iconic emblems of 20th century Britain

The red telephone box has been part of the landscape of Britain for a century. Jack Watkins takes a look at its history and impact — and worries for its continued survival.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

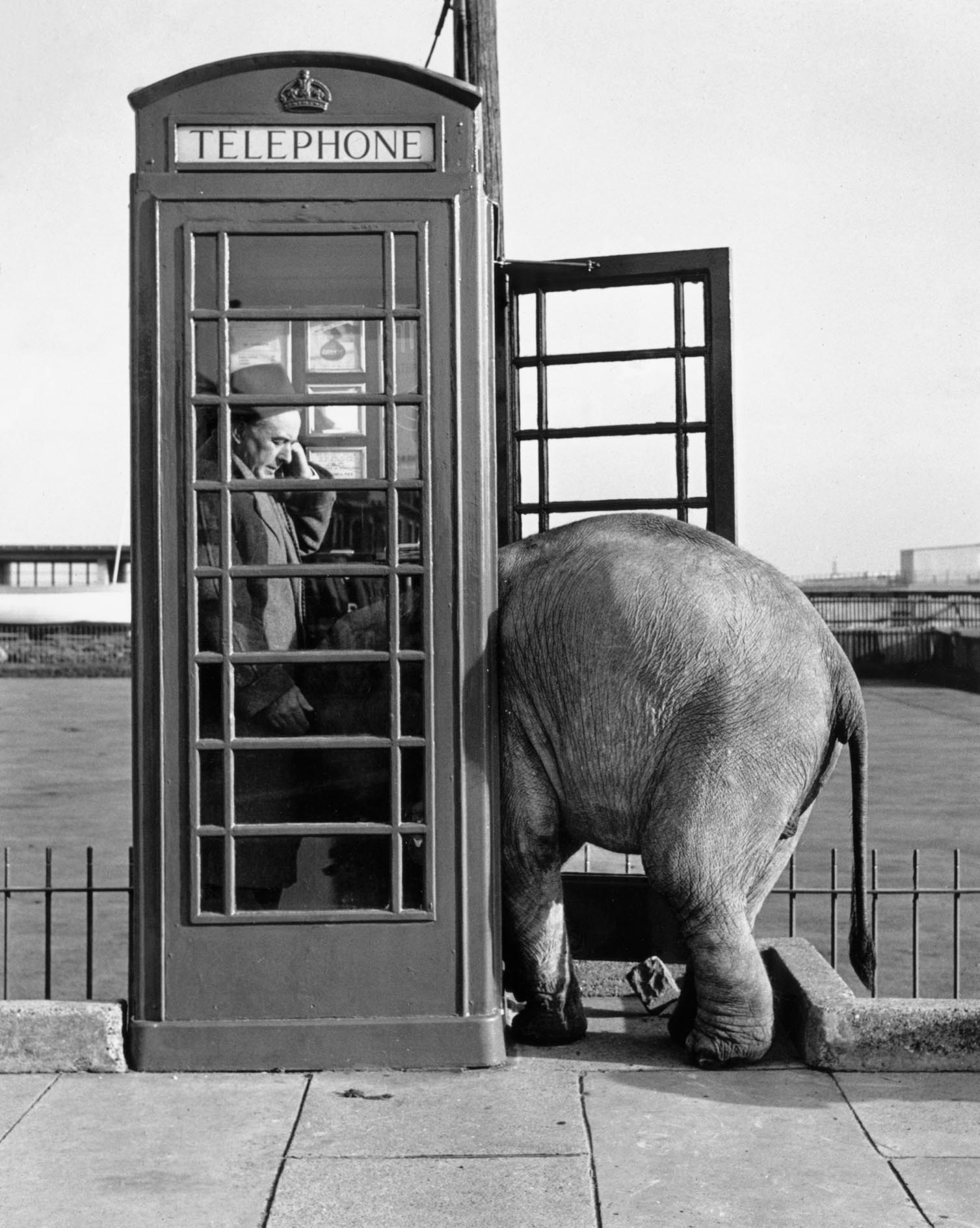

When the first Grade II-listing of a British telephone kiosk, a rare K3 at London Zoo, was announced in 1986, Minister for the Environment Lord Elton visited it to make a celebratory call for the benefit of the press. An exasperated sigh arose from the assembled throng when he emerged with a sheepish expression to tell them the phone was out of order.

The experience of making a call from a public phone box is unlikely to be something anyone does, or recalls having done in former days, with great warmth. Even so, the red kiosks designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in the 1920s and 30s, notably the neo- classical K2 and K6, are regarded with affection.

After the Post Office privatisation in 1984, the announcement by its successor, British Telecom, that it was replacing these sturdy cast-iron models and installing cheaper boxes, caused widespread dismay. Conservationists didn’t take the matter lying down. A campaign led by the Twentieth Century Society (originally the Thirties Society) ensued and, today, there are about 3,000 listed phone kiosks in Britain, some still serving their original function, others containing mini libraries or defibrillators or adopted by street vendors.

The first all-red kiosks appeared in 1926 as part of a plan by the General Post Office to produce a standardised design. An earlier attempt at creating a national telephone box, the K1, white with a red door and window frames, had not proved popular on its introduction in 1921, partly owing to what was seen by some as an outdated, hut-like appearance.

However, Gilbert Scott’s K2, chosen after a Royal Fine Art Commission competition, incorporated motifs from Classical and neo-Classical architecture, particularly Sir John Soane’s mausoleum, in an elegant yet solid-looking, functional piece of street architecture.

The K2 had a domed roof and the pediments bore a Tudor crown, pierced for ventilation, below which was a frieze bearing the word ‘Telephone’. There were fluted mouldings, three sides carried Georgian-style glazing panels, and the door was made of teak.

The expense and size of the K2 meant that, although 1,700 were manufactured by 1934, they were mainly confined to London. Gilbert Scott produced the smaller K3 in 1929 for nationwide use, painted cream in response to complaints about the K2’s bold red, but savings accrued from ditching cast iron for concrete were outweighed by the material’s tendency to crack.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Thus it was the K6, a modified version of the K2 designed to commemorate George V’s Silver Jubilee in 1935, that became the recognised red telephone kiosk.

The K6 was 8ft 3in high (the K2 was 9ft 3in) and lighter. The entablature was much reduced. Gone were the Grecian mouldings and the window panes were wider. It took up less space. For more than 25 years it reigned supreme.

Despite subsequent attempts to produce new designs, none came close to matching it, the last of the red telephone boxes being Bruce Martin’s minimalist K8, introduced in 1968.

These days, phone boxes of all types are under threat, not merely from BT philistines, but from under use. Even listed red kiosks look in need of a lick of paint.

The Twentieth Century Society recently celebrated a ruling by Ofcom stipulating that if more than 52 calls had been made from a phone box in the past year, it would be safe.

‘Why not do your bit to save these iconic structures and call a friend?’ the charity urged. A new campaign may be required.

The red phone box's architect: Sir Giles Gilbert Scott

Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880–1960) designed Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral and the Battersea and Bank- side power stations. Although it may seem ironic that a humble telephone box is his highest-profile creation, as the late architectural writer Gavin Stamp argued, the classically conceived K2 has ‘a monumental presence’.

Gilbert Scott’s K2 prototype (listed Grade II*), complete with timber floor, stands on the western side of the entrance portal to Burlington House on Piccadilly. A companion K2 (Grade II) stands on the eastern side of the portal. Neither are owned by BT any longer, but are still in service, beautifully maintained by the Royal Academy.

This is more than can be said for the many listed K6s on London’s streets, which look increasingly forlorn. However, a happy-looking ensemble (below) remains on Carey Street in Holborn, WC2, on the north side of the Royal Courts of Justice. Two K2s either side of a pair of K6s allow you to appreciate the differences in size and detail between the two types:

Red telephone boxes: 7 fantastic alternative uses for a British icon

Distinctly British, but rendered obselete by the march of the mobile, the red telephone box is finding new purpose, as

Jack Watkins has written on conservation and Nature for The Independent, The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. He also writes about lost London, history, ghosts — and on early rock 'n' roll, soul and the neglected art of crooning for various music magazines