Curious Questions: Why do barristers and judges wear wigs?

Like marmalade on toast, saying sorry and the Shipping Forecast, there are few things more typically British than the courtroom wig. Agnes Stamp explains why our barristers and judges wear them.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

They are the undeniable emblem of our judicial system. Perukes, worn together with robes, have been a mainstay of courtroom dress from about 1685, bringing an air of solemnity and formality to proceedings. In the case of the criminal courts, they once helped to safeguard the identities of the judges and barristers involved, too.

Throughout the 17th century, the ‘correct’ length of hair for men was much debated and, by the mid 1640s, when hair was worn long, hairpieces and wigs began to appear. By the following decade, the practice of wig-wearing was widespread across Britain, in spite of continuing criticism from puritans and satirists. Clergyman and critic Thomas Hall declared in 1653 that ‘these Periwigs of false-coloured haire (which begin to be rife, even amongst scholars in the Universities) are utterly unlawful, and are condemned by Christ himself’.

It was, of course, the court of the ruler that defined the dress code for polite society. Following in the (high-heeled) footsteps of his cousin Louis XIV, who had popularised wigs among the French aristocracy, Charles II brought the fashion to Britain. Samuel Pepys records the King dressed in a periwig in April 1664 and, thereafter, the royal accounts list many ‘heads of hair’ as they evolved into an essential part of male dress and, indeed, ‘undress’.

The Sun King and Charles II both suffered from premature balding. Both were also notorious womanisers (according to the diarist John Evelyn, Charles II was ‘addicted to women’) and some have speculated that the hair loss was, in both cases, a symptom of syphilis, so wigs were used to disguise the condition. They also helped remedy another common problem of the period: lice.

Medical deception aside, flowing wigs became symbols of status, because they were expensive and required correct manners and deportment to keep them in place. As the 17th century gave way to the next, the wig trend grew for both sexes.

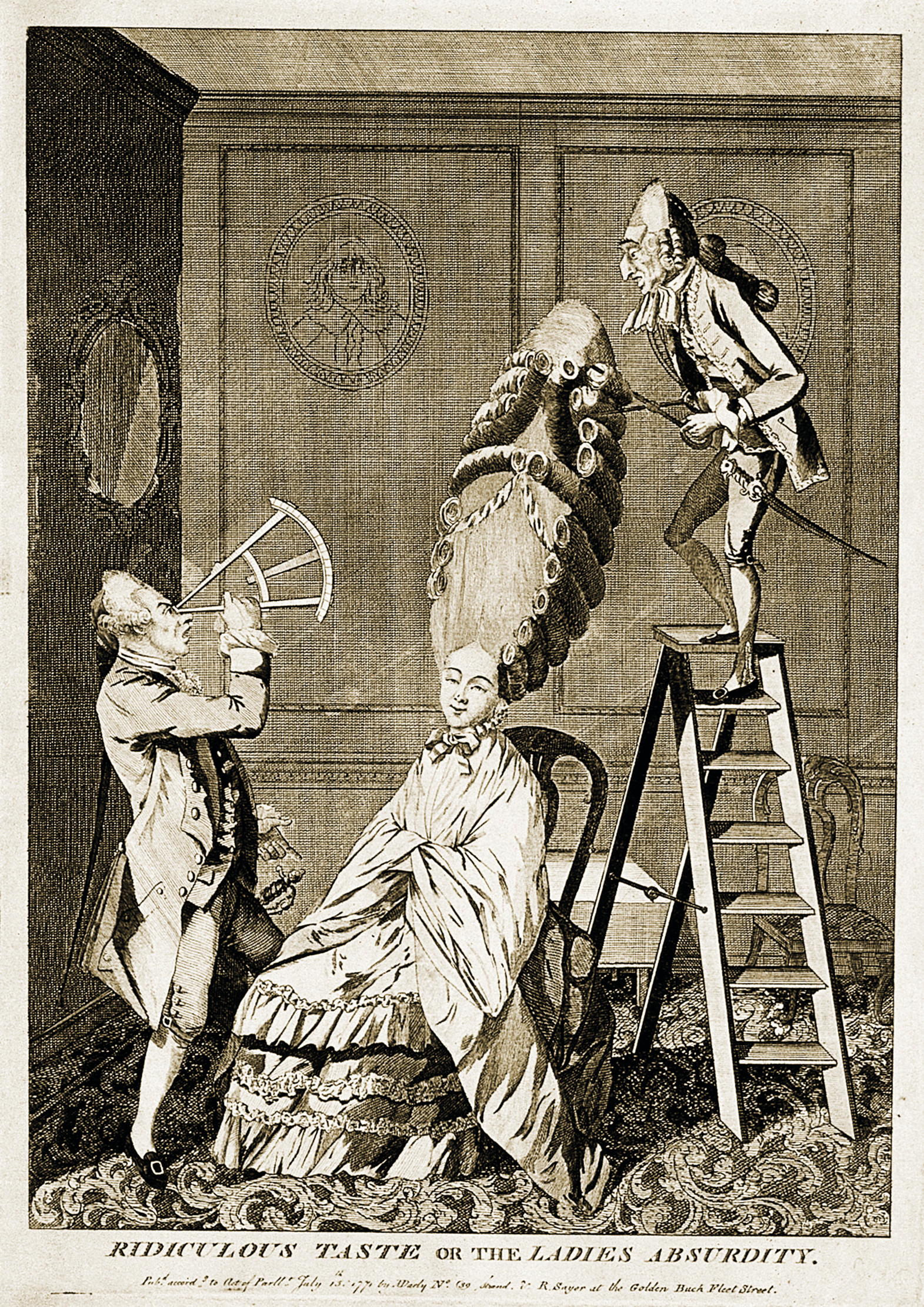

Made from human, horse or goat hair, wigs were thickened with pomatum (grease, which frequently went rancid), heavily powdered and perfumed (with ambergris, musk, bergamot, violet and others) and some styles towered at almost a yard high. Satirists spoke of ‘mountains of hair’ and a poem entitled The Ladies’ Head-Dress published in the London Magazine in 1777 suggested that husbands might get a shock behind closed doors: ‘But never undress her — for, out of her stays/You’ll find you have lost half your wife.’

In Hogarth’s The Five Orders of Perriwigs as they were Worn at the Late Coronation Measured Architectomically (1761), he satirises the fashion for wigs, comparing the beauty ideals and hairstyles of the period with the five orders of Palladian architecture. Hogarth’s five canons are Episcopal (the clergy), Old Peerian or Aldermanic (city officials and peers), Lexonic (lawyers), Composite or Half Natural and ‘Queerinthian’, representing the most ornate and effete.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In the 1770s, the macaronis, a group of young men who favoured towering wigs and foppish dress, came under fire from fencing master and memoirist Henry Angelo, who complained that ‘a solid pound of hair powder was wasted in dressing a fool’s head!’.

What goes up, must come down and, during the reign of George III, wigs fell out of favour for all but coachmen, bishops (who were eventually given permission to abandon wigs in 1832) and the legal profession. When William Pitt’s government passed The Duty on Hair Powder Act of 1795 to fund the Napoleonic Wars, the powdered wig was rejected by the British people. At that time, a single hairstyle could use at least a pound of hair powder and a tax on this was estimated to yield about £200,000 a year.

However, the custom of wig-wearing in the courtroom has endured. Despite changes to court dress code in 2007 — the then Lord Chief Justice Baron Phillips stated that ‘after widespread consultation it [had] been decided to cease wearing wigs…in the civil and family jurisdictions’ or when appearing in front of the Supreme Court — wigs remain commonplace during criminal proceedings, and many barristers elect to wear them throughout civil hearings, too. Here’s hoping perukes are still around for at least another three centuries.

Agnes has worked for Country Life in various guises — across print, digital and specialist editorial projects — before finally finding her spiritual home on the Features Desk. A graduate of Central St. Martins College of Art & Design she has worked on luxury titles including GQ and Wallpaper* and has written for Condé Nast Contract Publishing, Horse & Hound, Esquire and The Independent on Sunday. She is currently writing a book about dogs, due to be published by Rizzoli New York in September 2025.