Carla Carlisle: It's taken me years, but I finally understand my father's dying gift to me

Carla Carlisle on learning to slow down — and how little life might mean if we don't.

My father did not come to England to live with us. He came to die with us. What I didn’t understand was the honour: in the midnight of his life he wanted to be with his daughter who lived 3,000 miles away. He left behind his home, his books and his beloved dog. He arrived with a grim diagnosis and a single suitcase, which contained an envelope stuffed with insurance papers, his birth certificate, the journal he wrote in the 1960s, his Second World War dog tag and the letters I’d written home over three nomadic decades.

He also brought me a small book called Meditations For Women Who Do Too Much. I’m not sure I opened it in his lifetime, which turned out to be barely a month. He died in his sleep, a departure as full of grace as his life. In the drawer of the nightstand by his bed, I placed the meagre possessions he had arrived with: Social Security card, driving licence, glasses, watch, American Express card, passport — the prosaic memento mori of modern life. I slid the book into a shelf full of early Penguin paperbacks.

Over the years, I’d feel a thump of guilt: I never thanked him for the book. Was I too proud of doing so much — husband, child, farm, vineyard, restaurant, sheep, chickens, dogs, deadlines — to be grateful? Did I hanker after paternal praise, not wisdom offered in his deep Southern baritone: ‘Slow down, Sugar. Look at the sunrise. Come to your senses.’

It’s taken a long time to understand what he was telling me. Ten years ago, I reviewed a book in these pages called World Enough & Time: On Creativity and Slowing Down by Christian McEwen, a Scottish writer who made the reverse journey and lives in America. When I searched for it online, all I found was two lines: ‘Her prose is poetry, as clear as snow melt. If you think you are too busy to read this book, this is the book for you.’ I still stand by that.

It is a literary feast, but what I remember most is the writer urging the reader to ‘refuse and choose’, to resist ‘the siren call of technology’. The book was written before every ticket purchase/call for medical help/bank query required a smartphone, but the soul of the book is intact. I still return to it when my attention forsakes me.

"When information becomes abundant, attention becomes a scarce resource"

Which is saying something, as I have towers of unread books, proof that I don’t slow down enough and read. One slim volume has lingered on my bedside table for nearly a year. I’ve known the writer Casey Schwartz since she was a baby, she’s the daughter of one of my oldest friends. Her book has a heart-stopping title — Attention, A Love Story — and it’s about the very essence of slowing down: paying attention. This week, I finally began reading it. My only hope was I would be able to concentrate long enough to say I’d read it, but I couldn’t put it down.

‘This story begins with Adderall.’ That’s not an opening line that many readers of this magazine would know about. Adderall is a prescription drug that promises pure, distilled attention whenever you need it. Like Ritalin, it is one of the hottest drugs on the US campus black-market scene. It also has followers with traders, lawyers, lorry drivers, chefs and poets. Humble columnists tend to rely on coffee and digestive biscuits, deadlines and sheer luck to turn ideas into words, but the dream of distilled attention is our every prayer.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Ms Schwartz writes unflinchingly of the years in which her ambition to achieve was fuelled by Adderall, starting in her first year at Brown University. She describes her many attempts over 10 years to end her addiction, even as an academic highflyer exploring all the scientific, psychological and philosophical studies on how humans learn and how they lose concentration. Her level of attention and her intrepid journeys for research make the reader wonder how this brainy woman ever felt she needed to enhance her powers of concentration. Then again, there is this greedy monster called ‘High Expectations’.

Attention, A Love Story is scholarly and brave. It’s also an urgent exploration of how we have reached a time that is profound and possibly irreversible: we cannot concentrate. It is a worldwide epidemic, diagnosed and undiagnosed, of attention deficit disorder, affecting children (more boys than girls) and adults, the young and the old.

Even in my rural universe, it is easy to see how it has spread. No one now does only one thing. Once upon a time, the farmer ploughed his fields, a task that required the rhythm of repetition and concentration. Now, that farmer sits on a machine that has computers directing every move. A phone mounted on the dashboard combines commodity prices with Coldplay, the selling of wheat with the purchasing of fertiliser, against the background of Farming Today on iSounds. The crops might be timeless and organic, but the farmer’s tasks are not.

It’s tempting to blame the collapse in concentration on technology, but, in 1798, a Scottish doctor, Sir Alexander Crichton, observed that some people were unable to focus, were impulsive and easily distracted. More than 80 years ago, Aldous Huxley wrote: ‘Men have always been prey to distractions, which are the original sins of the mind.’ Shortly before she died in England in 1943, the French philosopher Simone Weil wrote: ‘Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.’ In the 1970s, before we all had smartphones, the Nobel prize winner Herbert Simon predicted that: ‘When information becomes abundant, attention becomes a scarce resource.’

It’s late in the day, but I now understand the gift — Be still. Practice silence. Pay attention — that my father brought on his last journey. I have ditched the word ‘multi-tasking’ from my life. Pinned above my desk are the words of the English writer Oliver Burkeman: ‘When you get to the end of your life, the sum total of all the things you paid attention to will have been your life.’ It’s like a message in a bottle from my father. Rare and pure.

Credit: Richard Cannon

The chickens of Wyken Hall: Mischievous, adorable and the best listeners a person could ask for

‘In my left-leaning youth, they would attend meetings, but my comrades voted to remove them. That was when I realised

Credit: Getty Images

Carla Carlisle: 'I’m about to expand on my belief that reading fertilises our memories and allows us to visit our past without getting hurt when I see her eyes wander off towards Monty Don'

Books create a powerful connection with the home of your youth, finds Carla Carlisle.

Credit: Alamy

Carla Carlisle: 'We took it for granted that we could travel the world and live wherever we wanted... Now the dice is loaded against our children and against the planet. What were we thinking?'

Carla Carlisle on being a pessimist, making lists, and seeing snow for the first time.

Carla Carlisle: 'Who thought visas that will expire on Christmas Eve was a good idea? The sooner they delete Bing Crosby’s I’ll be home for Christmas from the Department for Transport playlist the better'

Carla Carlisle does her very, very best to stay positive — and just about pulls if off.

Credit: Alamy

Carla Carlisle: 'Truth is a rock. Chip away at it enough and you end up with gravel, then sand'

'I’m not naming names, but here’s what I’m sick and tired of: anarchy, serial dishonesty, sloth, high drama, bar-room brawls

Credit: Getty

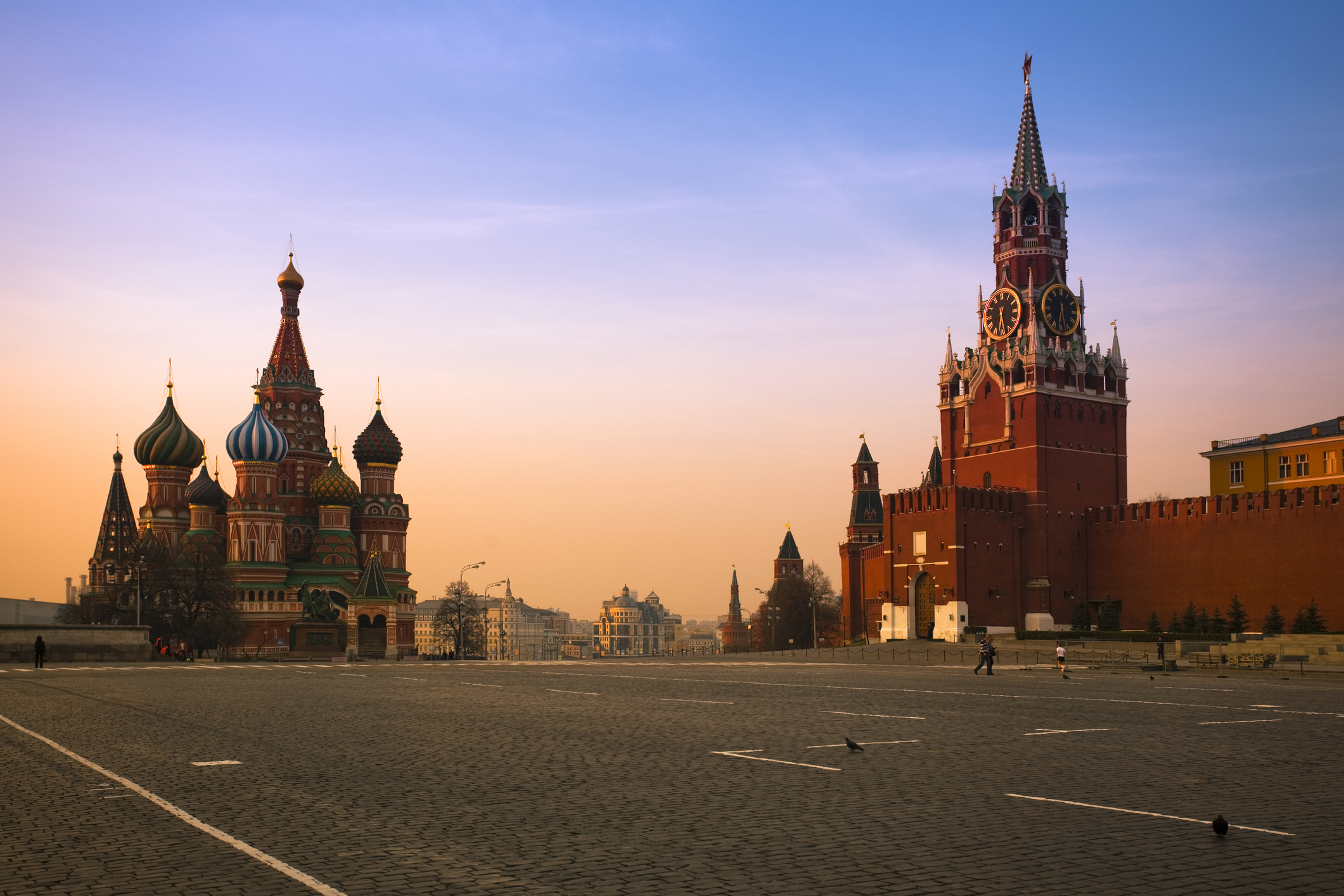

Carla Carlisle: 'You don’t need a map to tell you that East Anglia and Russia are closer than they look'

'It was like a Tarantino movie where the bad chase the bad,' says our columnist Carla Carlisle as events in

Carla Carlisle: Poetry, bird flu, and galloping about doing good

Carla Carlisle talks about how poetry inspired her to do good deeds – and how one deed in particular now seems

Credit: De Agostini via Getty Images

'It took my son and daughter-in-law a weekend to set up an online shop... In a week, we sold £10,000 of wine that was languishing in the bonded warehouse'

Carla Carlisle's lockdown has taken her farm shop to places she'd never imagined — but now she's there, she's not

Carla Carlisle: Wallis Simpson's great gift to Britain? Swapping vain, impulsive Edward for the patience, steadiness and kindliness of George and Elizabeth

Carla Carlisle may be a free-born American, but she doffs her cap to the late Queen, the new King, and

Credit: Jackson-Stops

An idyllic Suffolk rectory with walled garden, croquet lawn and full of 18th century charm

A house in Suffolk's 'Constable country' has come to the market, offering an idyllic rural escape yet within an hour