Seven astonishing books to read which will change your understanding of the history of the world

If you were left a tad disappointed by your Christmas presents, you can console yourself with two things. Firstly, by reminding yourself that it really is the thought that counts; and secondly, by putting things right with one of these astonishing and eye-opening tomes, picked out by Barnaby Rogerson.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Arabs by Tim Mackintosh-Smith

Tim Mackintosh-Smith has spent most of his adult life in the Yemen and the rest of it tracking down Ibn Battuta, the greatest travel writer of the Muslim world. In Arabs (Yale, £25), he concentrates his attention more on language and culture than religion or empire and gives us a dazzling, virtuoso chronicle of 3,000 years of Arabic achievement.

King of the World by Philip Mansel

Philip Mansel grew up in the heyday of the Marxist stranglehold over academic history, so he went his own way, wrote a dozen books and, in the process, helped to establish the Society for Court Studies and the Levantine Heritage Foundation. King of the World (Allen Lane, £30), his life of Louis XIV, has no doctrinal axe to grind and is informed by a restless personal quest.

Was this man, who created the highest expression of French culture, a genius or a self-obsessed monster? Was this king, who struck out at Brussels, Genoa, Siam, the Dutch and the Huguenots because he wanted respect, a terrorist? How do we match these murderous actions with his exuberant zest for life — for building, dancing, gambling, hunting and planning the most wonderful gardens and entertainments?

The Anarchy by William Dalrymple

I come from the last generation of British schoolchildren taught about the victories of Robert Clive in the history classroom. There followed an embarrassed silence of 50 years—so much so that a recent history graduate who came to work for us, in proud possession of a first-class degree, had never heard his name.

This whitewashing of history was mirrored in a different form within the classrooms of India, which maintained an active indifference to the Mughal Emperors, despised as alien conquerors. All of which makes William Dalrymple’s achievement more astonishing. The Anarchy (Bloomsbury, £30), which charts the rise of the East India Company, is the capstone in a succession of four books with which he has single-handedly managed to get the British to acknowledge the violence and rapacity of their history, as well as relishing the demonic energy and linguistic ability of many of their ancestors, and even reviving within India a scholarly interest in the Mughals.

Violencia by Jason Webster

Jason Webster first wrote a trilogy of travel books exploring Spain, followed by a series of detective novels. He has poured all he has learnt on the ground, together with his story-telling fluency, into Violencia (Constable, £25), explaining recurrent themes, enduring strengths and divisions within the complex landscape of Spanish history.

Through bite-sized chapters that allow us to enjoy the individual stories, he shows us that the Spanish experience, from Crusaders and the first colonial empire to ethnic cleansing and the clash of Fascism against Communism in the Civil War, should not be seen in isolation, but as a prelude to what Europe would soon endure.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Islamic Empires by Justin Marozzi

Justin Marozzi has ridden camels across the Sahara, written illuminating accounts of Hero-dotus, Tamerlane and Baghdad and advised the governments of Somalia, Libya and Iraq. In Islamic Empires (Allen Lane, £25), comprising 15 pocket portraits of cities of the Muslim world at a crunch point in their history, he gives us a vivid, candid and entertaining immersion into a complex subject.

The Boundless Sea by David Abulafia

David Abulafia is a professor in landlocked Cambridge, but empowered by a Sephardic ancestry that links him with Andalusian poets, Kabbalist mystics and the docks of Essaouira in Morocco. He also has a genius for reframing history, for shaking our assumptions and placing new peoples and concepts under the limelight.

In The Boundless Sea (Allen Lane, £35) Prof Abulafia gives us the story of the world as shaped by the pulse of its maritime trade routes. They also rise and fall just like an empire, but in this narrative, subtitled ‘A Human History of the Oceans’, our heroes are merchants, captains, carpenters and navigators, drawn from a rich cast of liminal sea peoples: Polynesians, Portuguese, Phoenicians, Pisans and Frisians.

In the Name of God by Selina O’Grady

Selina O’Grady’s In the Name of God (Atlantic Books, £25) is a tightly focused study of why various regimes have practised tolerance, usually by autocrats for the most cynical reasons of state, set against the politics of intolerance — and persecution of a minority — that has invariably been led by charismatic leaders advancing a populist, if not a patriotic, cause.

Jason Goodwin: In memory of Norman Stone, my tutor, guide, world traveller — and friend

Jason Goodwin pays tribute to an old friend and mentor.

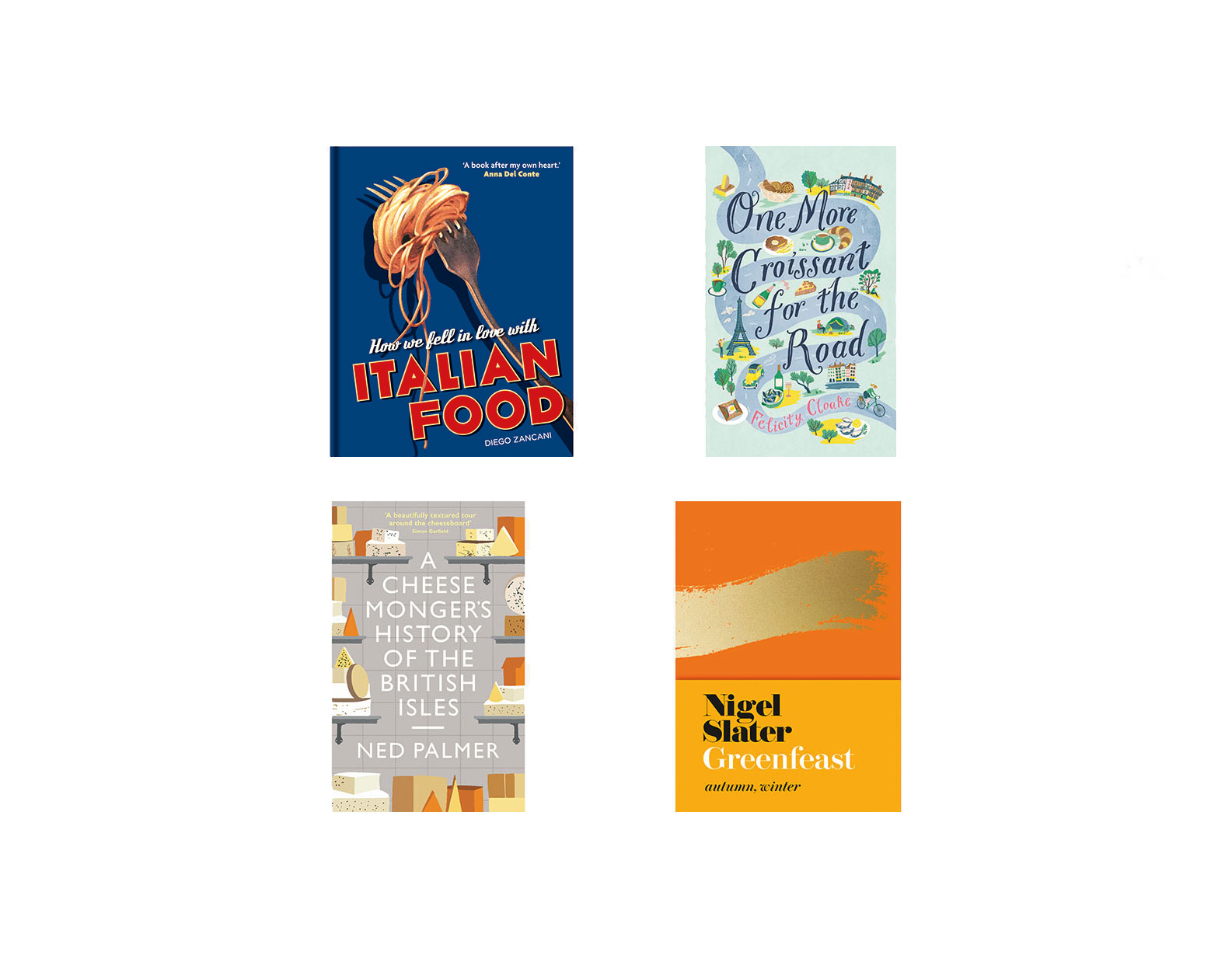

Nine books about cooking that make perfect Christmas gifts for foodies, from Nigel Slater's latest to a book that 'deserves a Michelin star'

Leslie Geddes-Brown devours the latest cookery books to hit shelves, from a study of Italian food to a tour of

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: 'We have books all over the floors and carpets on the furniture'

Our columnist Jason Goodwin talks about jam jars, duvets and the books which are taking over his house.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.