Jonathan Self: The rat who came to lunch in a fetching shade of Farrow & Ball

Jonathan Self tells the story of a rather friendly rodent who seems happy to ride his luck.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

‘It’s so quiet,’ said the house guest from London, pushing back his chair, ‘and relaxed. The countryside is’ — he searched for the mot juste — ‘tranquil.’

It was after lunch, one of those rare, long, languid, outdoor, perfect-summer-day lunches that occur far too infrequently, and we were sitting on the terrace gazing at the sea. I wanted to reply: ‘Are you mad?’ But, not wishing to be rude, I only muttered: ‘Up to a point, Lord Copper,’ as I watched Pulling limp out from under a bush, collect a crust that had fallen from the table and limp back to cover.

It was only the fourth sighting ever of Pulling, named after the narrator of Travels With My Aunt, who once threw a stone at a rat with a broken leg. Our Pulling was first spotted during a more typical Irish summer lunch: we were inside, staring out at the rain. Oblivious to our presence (given how much noise the dogs were making, Pulling must also be deaf), he stood on his back legs and nibbled meditatively at something he had found under the table.

Opinion was divided. The musophobic were in favour of releasing Elsa, our blue whippet, who, without breaking her stride, once despatched with a single snap of her jaws a rat rash enough to run in front of her. A visitor who might be said to suffer from decorexia remarked that the rat’s colouring was a lovely combination of Farrow & Ball’s London Clay and Mole’s Breath.

One of my sons recited Browning: ‘Rats!/They fought the dogs, and killed the cats,/And bit the babies in the cradles,/And ate the cheeses out of the vats,/And licked the soup from the cooks’ own ladles.’

The conservationists pleaded for his life. The literary proposed names: Basil (from Fawlty Towers), Templeton (from Charlotte’s Web) and Scrabble (from Little Women). We were so busy that none of us noticed that our subject was no longer among those present.

Rats are supposed to be nocturnal, but, so far, Pulling has always hobbled into view at about 4pm, leading me to believe that either he gets desperately hungry at that hour and can’t wait for dinner or he has a death wish. It seems a miracle to me that the barn owl who resides in one of our old stone sheds, the fox family living in the little wood on the far side of the home field, the neighbourhood stoats, a local cat or, of course, Elsa, haven’t yet done away with him, especially as he moves so slowly. Which brings me to what I would have liked to say to the house guest.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The countryside is anything but relaxed. Its animal occupants are as busy as we are looking for food, building their homes, romancing, raising their young, socialising and avoiding danger. The pheasant nesting in the dense briar patch behind our stables takes her 11 fledglings for a walk every day at midday, doubtless to avoid the foxes. The otters on the beach start their fishing at about 9pm, doubtless to avoid us. The hares may be all but invisible (‘Behold the ever-tim’rous hare,’ as Samuel Thomson enjoins us, ‘Already quits her furzy shade,/And o’er the field, with watchful care,/Unseen to nip the sprouting blade’), but they are far from idle.

Nature isn’t tranquil either, for death is both everywhere and necessary. As Charles Mackay wrote: ‘In Nature nothing dies. From each sad remnant of decay, some forms of life arise.’

Scant comfort, I fear, for the doomed Pulling.

How to get rid of rats

Getting rid of rats isn't easy: they're a notoriously destructive and stubborn breed, and require patience and determination to eradicate.

Jonathan Self: Don't measure your life in years — measure it in dogs

Jonathan Self celebrates a birthday for a beloved dog.

Credit: Alamy

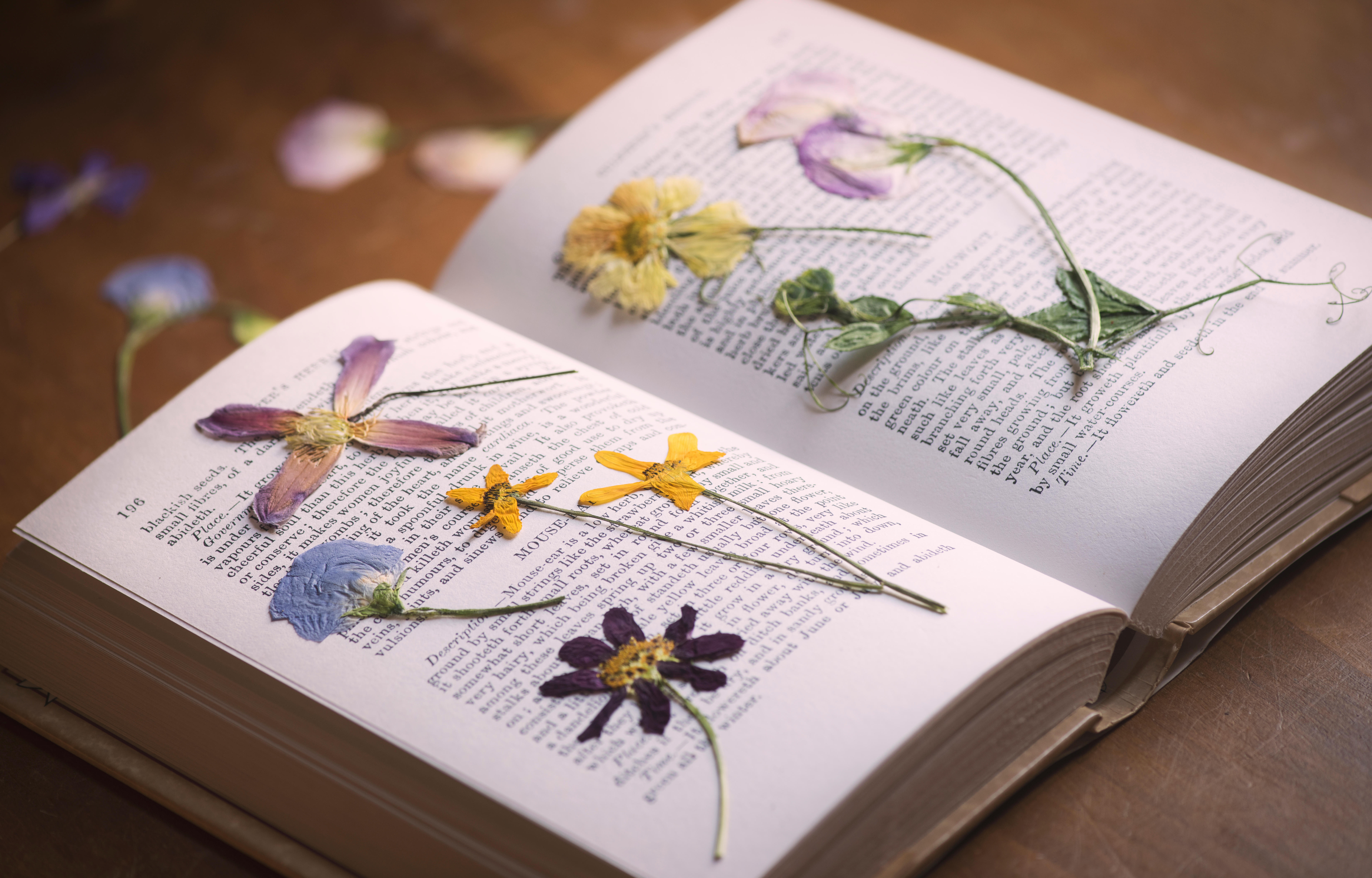

Jonathan Self: The collections that made me, from pressed flowers to my 416 'do not disturb' signs stolen from hotels

Who knew that pressing flowers could be thrilling and skilful? Jonathan Self, a self-confessed 'obsessive collector', tells all.

Jonathan Self: 'In Ireland, summer smells sweet, effervescent and damp. In Tuscany, one almost has to push one’s way through it'

Jonathan Self's recent move to Italy has brought a fresh challenge. Or rather, a hot and heavy one.

Credit: Alamy

Jonathan Self: 'To be in a foreign country is thrilling. Everything is new. One is constantly on one’s mettle. It is like being a child again'

Jonathan Self's scuppered plans force him to reflect on how the joy of travel mixes with the delicious ambivalence of

Credit: Getty Images

Jonathan Self: 'Ten yards from shore, I felt completely and utterly alone, the last man on earth'

A wintry dip in the ocean revitalises Jonathan Self.

Credit: Alamy

Jonathan Self: 'Town folk know pleasures, country people joys'

Live in a village and you'll live longer, says Jonathan Self — just be prepared for everyone to know your business.

After trying various jobs (farmer, hospital orderly, shop assistant, door-to-door salesman, art director, childminder and others beside) Jonathan Self became a writer. His work has appeared in a wide selection of publications including Country Life, Vanity Fair, You Magazine, The Guardian, The Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph.