Curious Questions: How did curry become Britain's national dish?

Martin Fone takes a look at the first Indian restaurant in Britain, discovering what was on its first menu, and finding out how lager became the traditional accompaniment to curry dishes.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Steak and kidney pie? Sunday Roast? Fish and chips? Roast beef and Yorkshire pudding? It’s impossible to define what is Britain’s national dish, but curry has as good a claim as anything.

As of 2015 there were around 12,000 Indian restaurants in the country, employing 100,000 people and generating revenues of £4.2 billion. That said, the word ‘Indian’ is a misnomer: most of the traditional curries served in Britain area actually Bangladeshi, and many of the restaurant owners can trace their roots directly to the eastern Bangladeshi city of Sylhet.

Ironically, Sylhet is not famed for its curries, rather for a deep fermented paste made from dried punti fish. Perhaps this does not matter much as our preferences betray a peculiarly British take on the cuisine of the Sub-Continent; chicken tikka masala, called the nation’s favourite dish by Robin Cook in 2001, was first created in Glasgow and chicken Balti in Birmingham.

A green plaque on the wall of Number 102, George Street in London informs the passer by that it was the ‘site of the Hindoostane coffee house, 1810. London’s first Indian restaurant. Owned by Sake Dean Mahomed (1759 – 1851)’. Was this where our love affair with the Indian restaurant began?

Mahomed, born in Patna, was taken under the wing of Captain Godfrey Baker after his father had been killed in battle, serving as a trainee surgeon in the British East India Company. In 1782 he accompanied Baker to Cork in Ireland and during his stay there produced the first book to be written in English by an Indian, The Travels of Dean Mahomet (1794), a mix of autobiography and travelogue. By the turn of the 19th century he was on the move again, the lure of the bright lights of London proving too hard to resist.

Basil Cochrane, a so-called nabob who had made his fortune in India, flaunted his wealth by installing a steam bath in his house in Portman Square. He opened it up to the paying public, employing Mahomed to run it. One of the attractions on offer was a champooi, a form of body scrub combining a massage with cleansing, almost certainly Mahomed’s idea, making him the man who introduced shampooing into this country.

Mahomed had grander ideas, though. In a notice printed in The Morning Post on February 2, 1810 he announced that as ‘a manufacturer of real currie powder’ he had established the ‘Hindostanee Dinner and Hooka Smoking Club…where dinners, composed of genuine Hindostanee dishes, are served up at the shortest notice’. One of his principal patrons was ‘Hindoo Stuart’ as Charles Stuart was dubbed, a man fascinated with all things India. There was even a take-away service; ‘such ladies and gentlemen as may be desirous of having India Dinners dressed and sent to their own houses will be punctually attended to by giving previous notice’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Perhaps the business idea was flawed. Many who had served in India, and who should have been Mahomed’s natural clientele, had Indian servants of their own and so had no need to visit a restaurant to taste the exotic delights of a curry. In a desperate change of tack, Mahomed started to appeal directly to Indian gentlemen, offering, as he claimed in The Times of March 27, 1811, an establishment ‘where they may enjoy the Hoakha, with real Chilm tobacco, and Indian dishes, in the highest perfection, and allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England’. Alas, within a couple of years of its opening he had to file for bankruptcy. Under new management, the restaurant struggled on until finally closing in 1833.

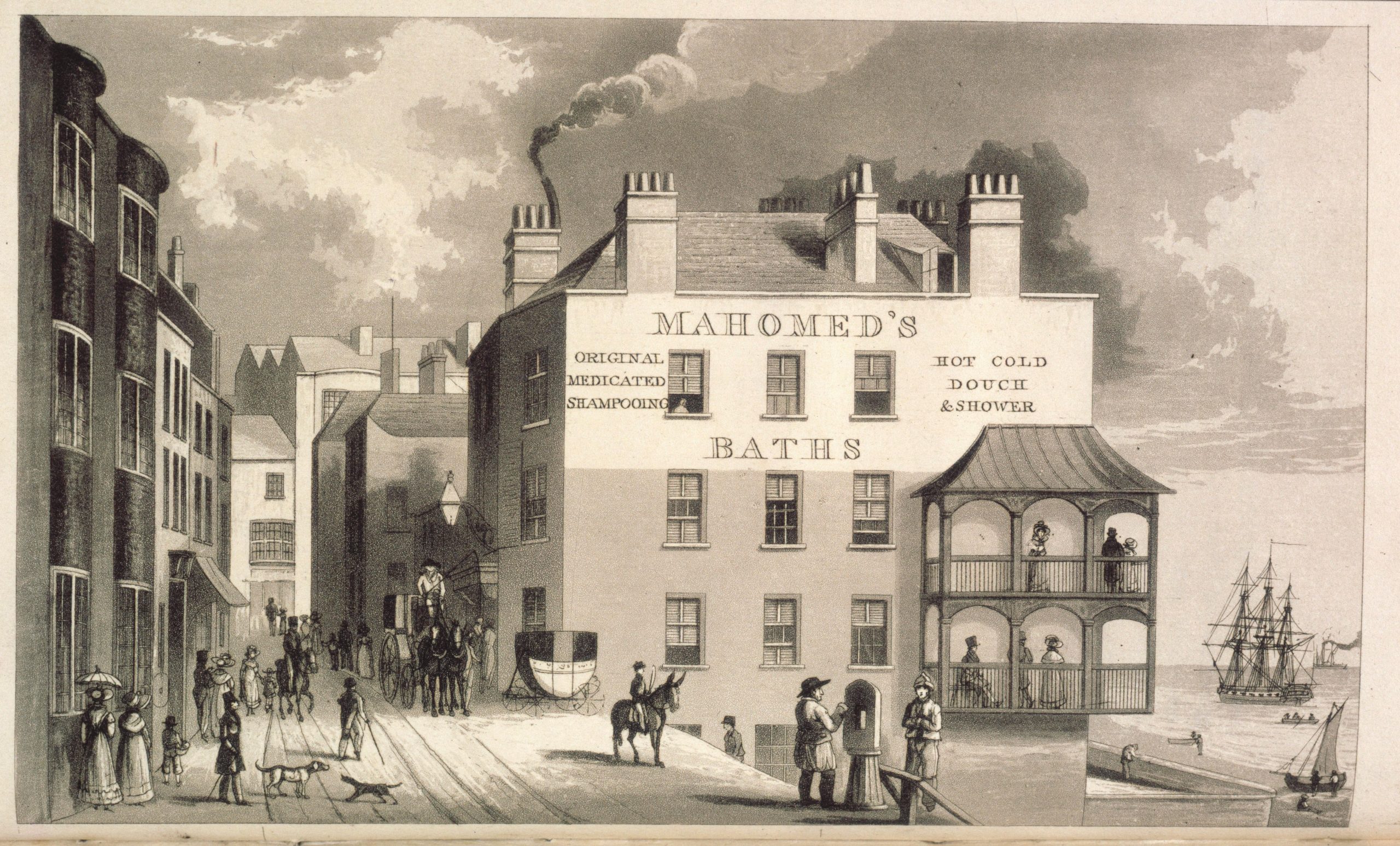

Luckily, Mahomed had his champooi skills to fall back on, opening the first commercial ‘shampooing’ vapour bath in England, in Brighton in 1814 on what is now the site of the Queen’s Hotel. It was a roaring success, Mahomed earning the sobriquet of ‘Dr Brighton’ and the appointment of shampooing surgeon to both Kings George IV and William IV.

But was Mahomed’s restaurant really the first? After all, Britain in the form of the East India Company had been operating in the sub-continent since the 17th century, establishing their first factory and warehouse in what is now Chennai in 1639. Spices were among the goods traded and those who served out in India must have brought back a taste for a curry, which offered a welcome contrast to the blandness of much of British fare at the time. To pander to these tastes the Norris Street Coffee House in London’s Haymarket was serving curry as early as 1733.

Hannah Glasse, the Mrs Beeton of Georgian England, included in her The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747) recipes for Indian pilau and, in later editions, extended her range to include Indian pickles and rabbit and chicken curry. Her recipe To make a currey the Indian Way advised the cook to use for two chickens ‘an Ounce of Turmerick, a large spoonful of Ginger and beaten Pepper’, cautioning that these ingredients ‘must be beat very fine’.

Shortly after its publication, Piccadilly-based Sorlie’s warehouse offered curry powder via a mail order scheme and curry and rice were specialities in several restaurants in the Piccadilly area during the 1780s. Mahomed’s Hindoostane, if it had a claim to fame, was probably the first restaurant owned by an Indian offering exclusively Indian fare.

A book described as a Comprehensive Late Eighteenth Century Manuscript Receipt Book and bearing the title Receipt Book 1786 was sold by Jarndyce Antiquarian Books at the ABA Rare Books fair in London in June 2018 for £8,500. Within it were two handwritten pages detailing the ‘Bill of Fare’ from the Hindoostane Dinner and Hooka Smoking Club, providing a fascinating insight into the range of dishes that Mahomed offered and their price.

Included among the twenty-five dishes on offer were Coolmah of Lamb or Veal at eight shillings each, the modern equivalent of £31, Lobster or Chicken Curry at 12 shillings (£47.50), and Makee Pullaoo at one guinea (£83). If you really wanted to push the boat out, a Pineapple Pullaoo would set you back 36 shillings, or £142. In addition, there was an extensive array of breads, chutneys and ‘various other dishes too numerous to mention’. The prices may suggest why Mahomed struggled.

Despite Mahomed’s misfortunes, curry was beginning to find favour, imports of turmeric, popular in spicing up cold meats and the principal ingredient in curry, tripled between 1820 and 1840.

Curry was promoted in the 1840s for its dietary and health benefits, regular consumption, so it was claimed, stimulating the stomach, invigorating the flow of blood, and creating a more vigorous mind. The Mutiny of 1857 rather put all things Indian in bad odour and it took over half a century for curry, notwithstanding royal patronage, to reclaim lost ground.

London’s first high-end Indian restaurant, the Veeraswamy, opened in 1926 — still trading, it was awarded a Michelin star in 2016 — and this is where the tradition of drinking lager with a curry may well have started. Prince Axel of Denmark, one of its regular patrons, would send over a barrel of Carlsberg every year. So popular did the drink become as an accompaniment to the spicy dishes on offer that the restaurant began importing it themselves. When waiters left to establish their own restaurants, they took the custom with them. Probably.

Kofta curry with stuffed parathas and cucumber raita

These curried delights will always be welcome.

Credit: Colony Grill

How to make kedgeree, the classic rice dish that makes a perfect weekend brunch

Kedgeree is a classic Anglo-Indian dish that's been hugely popular in Britain since Victorian times.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.