George Harrison's Garden: How the Beatle and his wife turned a 'tangled jungle' into a magnificent garden

When George Harrison first saw the famous Topiary Garden at Friar Park in Oxfordshire, it was a tangled jungle of overgrown yews. The work he began has been continued by his wife, Olivia, and, now, the display is back to its full glory, finds Charles Quest-Ritson.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Friar Park is a Gothic fantasy on the chalk downs just above Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire. It was famous 100 years ago as the most eccentric and extravagant new garden in England. Today, it is no less famous as the place that the former Beatle George Harrison, with his wife, Olivia, loved and restored.

Friar Park has an interesting history. The original house was built in the 1870s, then enlarged in the 1890s. Harrison’s own description was spot on: ‘Victorian Gothic Revival, mixed with a French château… really incredible.’ The same is true of the gardens, which were laid out by a rich and eccentric lawyer, Sir Frank Crisp, between 1889 and his death 30 years later. Crisp’s creations included a vast alpine rock garden that covered four acres, topped by a scale model of the Matterhorn, as well as a series of stalactites, caves, grottos and underground passages populated by a multitude of garden gnomes. Country Life was impressed and, over the years, published several laudatory articles about the garden.

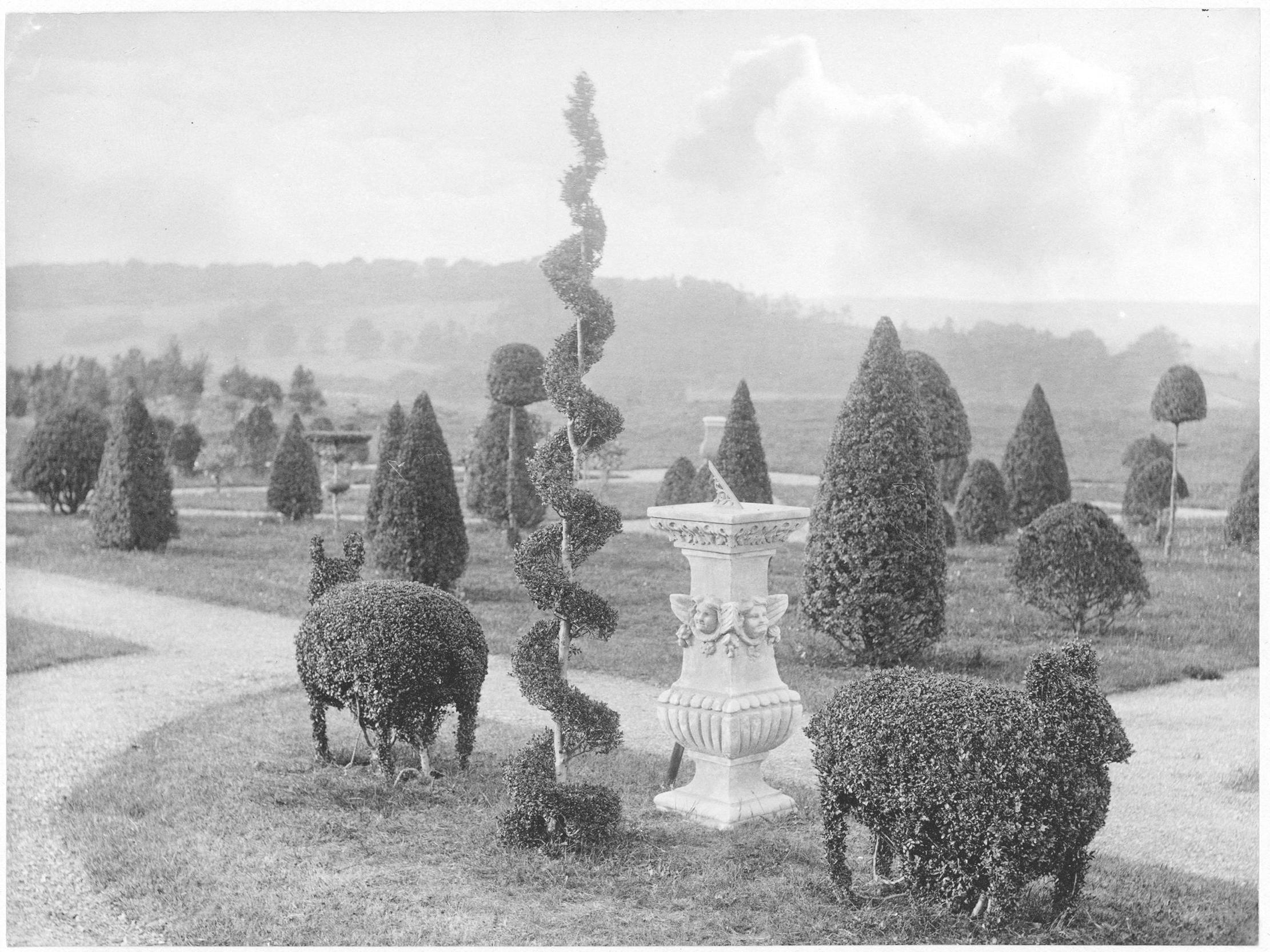

Crisp was a born collector and one of his passions was for sundials of every type, which he installed in an area he called the Dial Garden. Gnomons, astrolabes, armillary spheres and ring dials—all were corralled into his garden and mounted correctly. The layout copied the plan of the long-lost Labyrinth at Versailles in France, but with 39 sundials in place of the original fountains.

Each of Crisp’s dial-stands carried a motto, exactly as Louis XIV’s fountains each bore an inscription. But nothing was ever quite straightforward about Crisp’s architectural and horticultural fantasies at Friar Park. First, he added comic statues with further inscriptions. Next, he started to plant topiary yews among his sundials, many of them the upright form Taxus baccata ‘Fastigiata’, known as the Irish yew. Crisp trained them in eccentric shapes, not only vases, puddings and obelisks, but dumb waiters, spirals, cockerels and peacocks perched on top—plus a fine pair of topiarised sheep.

Friar Park was frequently open to the public during Crisp’s ownership. Sepia postcards were printed and sold for visitors to spread the fame of both house and garden. After his death in 1919, the estate was sold to Sir Percival David, a scholarly banker who built up one of the finest collections of Chinese porcelain in Britain. The garden was well maintained and open to the public right up to the outbreak of war in 1939.

The Second World War and the high taxation rates of the 1940s and 1950s put an impossible burden on the upkeep of large houses and gardens. Many were demolished. When Sir Percival put Friar Park up for sale in 1951, however, it found a buyer: an order of nuns, variously known as the Institute of Daughters of Mary Help of Christians or the Salesian Sisters of St John Bosco. Religious orders in Britain enjoyed a great boost in vocations after the war and the nuns—full of optimism—acquired Friar Park and ran a convent school.

There are pictures dating from the early years of their ownership of nuns busily clipping the yews in the topiary garden. It soon became clear, however, that the cost of maintaining the house and garden was way beyond their means. They tried, but failed, to obtain planning permission to carve up the garden into building plots, then decided that their best option was to sell the whole estate.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Enter Harrison, aged 27, puzzled, but intrigued by the house and garden, which he bought from the nuns in 1970 after his success as a musician freed him to develop his cultural and historical interests. Friar Park was an essential part of this personal development and its eccentricities appealed to his artistic temperament. He confessed that, when he saw the Friar Park estate for the first time, he felt as if he had seen it before.

His wife, who first came to Friar Park in 1974, thinks it ‘brought to mind Victorian Calderstones Park on the edge of Liverpool, which George knew when he was a pupil at the Liverpool Institute for Boys’. The garden’s eccentricities chimed with his creative sensibility and his love of history.

Harrison sometimes referred to the house at Friar Park as Crackerbox Palace, but, in 1970, it needed repair. Years later, he recalled the condition of the house at the time of his purchase: ‘It was all rotting—and nobody was interested. They were trying to pull it down and destroy it.’ He added, with justifiable pride: ‘Now, it’s a listed building.’

Repairing the house was a massive undertaking, but every part of the garden also called out for attention, as Harrison began to uncover and appreciate the structure of what remained of Crisp’s dramatic garden after nearly 30 years of neglect. Mrs Harrison has vivid memories of these years of rediscovery: ‘George used garden flame-throwers to clear the undergrowth and put two goats to clear the weeds and brambles on the rock garden. He hired and oversaw a team of local builders, who cleared ceramics and shopping trolleys out of the lake, which the nuns had allowed to be used as a dumping ground. And he personally oversaw the workmen he hired to cement the leaks and lay new pipework so that the lakes could be filled again.’ The topiary garden was completely overgrown, reduced to an impenetrable sea of bushes that had grown into each other and overrun by such weeds as ivy and brambles. Sir Frank’s sundials had long since disappeared.

The Harrisons quickly became enthusiastic, hands-on gardeners. Together, they set to work, each tackling separate areas of the garden. Years later, their son, Dhani, confessed—in his mother’s book George Harrison: Living in the Material World—that: ‘My earliest memory of my dad is probably of him somewhere in a garden covered in dirt… just continuously planting trees. I think that’s what I thought he did for the first seven years of my life. I was completely unaware that he had anything to do with music.’

The Harrisons knew what should be done to recover the topiary garden, once the weeds had been cleared. The overgrown bushes, some of them now small trees, were pruned back to their trunks. Yews respond well to hard pruning and, gradually, they all grew back thick and bushy once again. Over the years, new topiaries began to be carved, although most of them were maintained in simple shapes as columns and cones.

After her husband’s premature death in 2001, Mrs Harrison engrossed herself in the garden, putting her energy into finding ever more interesting species to plant and overseeing the upkeep and maintenance of the whole estate. She commissioned expert topiarist James Crebbin-Bailey to develop the topiary and gave him a free hand on how best to develop the individual specimens.

Mr Crebbin-Bailey says that Mrs Harrison’s intuitive understanding of what he sought to achieve was invaluable. He also adds that, when he began work at Friar Park, he had a strong sense of the spirit of George Harrison present throughout the garden and that this helped him to choose his designs. The traditional forms, such as cones, vases, urns, mitres, spirals and a rabbit (the sheep have long since disappeared), were supplemented by hexagons, concave shapes and, more particularly, groups of pagodas, bullseyes, waves and psychedelic forms. Mr Crebbin-Bailey is convinced that these innovative features, reflecting a search for spiritual enlightenment, were guided by Harrison himself. Almost all Crisp’s collection of sundials had long since been sold or stolen: Mrs Harrison has tried to assemble replacements, to capture the spirit of the garden as Crisp envisaged it.

It is hard to say exactly how many individual topiaries are there today. They are very difficult to count without missing some out or counting them twice. Estimates range between 161 and 166, all of yew, apart from 13 of box. It is probably the greatest concentration of topiaries in Britain. The distinctive shapes combine harmoniously with their neighbours, which is all the more important because some of the plants are as much as 15ft high and the gaps between them are often quite narrow. The balance between solidity and openness in a comparatively small space is crucial to the success of the composition. In short, the impeccably maintained topiary garden at Friar Park today is a masterpiece—one of the most important in all Europe.

Credit: Kenwood - John Lennon's house in St George's Hill, Weybridge - Knight Frank

Inside the mansion where John Lennon lived at the height of Beatles fame

John Lennon and his then-wife Cynthia bought this beautiful house in St George's Hill as The Beatles were at the

Credit: Knight Frank

A hot pink house in Hertfordshire where Hollywood royalty — including Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton — partied during the 1930's and 1950's

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor partied at this gorgeous — and very pink — house. Lydia Stangroom tells more.

Charles Quest-Ritson is a historian and writer about plants and gardens. His books include The English Garden: A Social History; Gardens of Europe; and Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World. He is a great enthusiast for roses — he wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses jointly with his wife Brigid and spent five years writing his definitive Climbing Roses of the World (descriptions of 1,6oo varieties!). Food is another passion: he was the first Englishman to qualify as an olive oil taster in accordance with EU norms. He has lectured in five languages and in all six continents except Antarctica, where he missed his chance when his son-in-law was Governor of the Falkland Islands.